The Ancient Protein Clock That Ticks Without DNA

TL;DR: Gut bacteria are revolutionizing medicine as scientists develop microbiome-based therapies to treat diseases from infections to autoimmune disorders, with FDA-approved treatments already available and personalized microbial medicine on the horizon.

In just a few years, doctors may prescribe a carefully engineered cocktail of bacteria to treat your depression, reverse your autoimmune disorder, or even prevent cancer. This isn't science fiction projected decades away - it's happening right now in hospitals, clinics, and labs around the world. The human gut microbiome, home to trillions of microorganisms that outnumber our own cells, is revealing itself to be not just a passive resident of our bodies but an active architect of our health. What scientists initially dismissed as mere "gut flora" now appears to be an organ system as vital as the heart or brain, orchestrating everything from immune responses to mental health. And for the first time, we're learning how to harness that power.

For decades, the gut was medicine's forgotten frontier. Researchers knew bacteria lived there, but the prevailing wisdom held that these microbes were either harmless hitchhikers or occasional troublemakers causing infections. Then came the Human Microbiome Project in 2007, a massive international effort to map the microbial communities living in and on our bodies. What scientists discovered stunned them: the gut alone hosts between 500 to 1,000 different bacterial species, collectively weighing about the same as the human brain and containing genetic material that dwarfs our own genome by a factor of 150 to 1.

But sheer numbers weren't the real revelation. The breakthrough came when researchers realized these bacteria aren't just present - they're active participants in nearly every bodily function. Your gut microbes produce vitamins, break down complex carbohydrates your body can't digest alone, train your immune system to distinguish friend from foe, and manufacture neurotransmitters that influence your mood and behavior. When this microbial ecosystem falls out of balance, a condition called dysbiosis, the consequences ripple through the entire body.

The evidence mounted quickly. Studies linked dysbiosis to inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even neurological conditions like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's. In 2024 alone, landmark advances showed connections between gut bacteria and autoimmune disorders, mental health conditions, and cancer progression. Suddenly, the question wasn't whether the microbiome mattered - it was how fast we could turn this knowledge into treatments.

The first microbiome-based therapy to gain widespread acceptance seemed, frankly, disgusting. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) involves taking stool from a healthy donor, processing it to concentrate the beneficial bacteria, and transplanting it into a patient's gut. It sounds medieval, but for people suffering from recurrent Clostridium difficile infections - a potentially deadly condition where harmful bacteria colonize the gut after antibiotic treatment - FMT proved nothing short of miraculous.

Early trials showed cure rates exceeding 90%, far surpassing conventional antibiotic treatments that often failed repeatedly. The American Gastroenterological Association now maintains a national FMT registry tracking outcomes and refining protocols. In 2022, the FDA approved REBYOTA®, the first commercial fecal microbiota product for recurrent C. difficile infection, marking a historic moment: live bacterial therapies had entered mainstream medicine.

But FMT was just the beginning. Researchers quickly realized they didn't necessarily need whole stool transplants - they could isolate specific beneficial bacteria or engineer microbial consortia tailored to particular diseases. This opened the floodgates for what the pharmaceutical industry now calls "live biotherapeutic products."

Companies are racing to develop next-generation microbiome therapies. Unlike traditional drugs that target human cells, these treatments work by rebalancing or editing the microbial ecosystem. Some use single bacterial strains with proven benefits. Others deploy carefully curated communities of bacteria designed to work together. Still others use engineered probiotics - bacteria genetically modified to produce therapeutic molecules directly in the gut.

Clinical trials are underway for microbiome therapies targeting inflammatory bowel disease, food allergies, metabolic disorders, and even autism spectrum disorder. In 2024, researchers reported a case of severe food intolerance completely resolved after FMT, suggesting potential applications far beyond infectious disease. The pipeline is expanding rapidly: as of 2025, the FDA is actively reviewing multiple microbiome-based therapies, with expectations for several approvals in the coming years.

To understand why microbiome therapies work, you need to grasp what happens when the gut ecosystem fails. Under healthy conditions, beneficial bacteria - primarily anaerobic fermenters that thrive in low-oxygen environments - dominate the gut. These bacteria break down dietary fiber into short-chain fatty acids, which feed the cells lining your colon and help maintain the gut barrier that keeps harmful substances out of your bloodstream.

When dysbiosis occurs, the ecological balance shifts. Recent research reveals that the primary driver isn't the bacteria themselves but changes in the gut environment - particularly oxygen availability. During inflammation or other insults, oxygen levels in the gut lumen increase. This favors facultative anaerobes (bacteria that can survive with or without oxygen) over the beneficial strict anaerobes. These opportunistic bacteria produce fewer beneficial metabolites and more inflammatory compounds.

The consequences cascade through the body. A compromised gut barrier allows bacterial fragments and inflammatory molecules to enter the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation. The immune system becomes hyperactive or, paradoxically, dysfunctional. Neurotransmitter production changes, affecting mood and cognition through what scientists call the gut-brain axis. Metabolic signaling goes awry, contributing to obesity and diabetes.

This understanding opens two therapeutic pathways. The first, "metabolism-based editing," involves introducing beneficial bacteria that can outcompete harmful species or directly supplementing missing metabolites. The second focuses on "strengthening host functions" - using drugs, diet, or other interventions to restore the gut environment to conditions that naturally favor beneficial microbes.

Consider the gut-brain axis, which has emerged as one of the most fascinating frontiers. Your gut bacteria produce or influence the production of neurotransmitters including serotonin, dopamine, and GABA - the same molecules targeted by psychiatric medications. About 90% of the body's serotonin is produced in the gut, where it's influenced by microbial activity. Studies have linked specific bacterial species to depression, anxiety, and even autism, raising the tantalizing possibility of treating mental health conditions by modulating gut bacteria.

For patients and clinicians, the critical question is: what can microbiome science do for you today? The answer depends on the condition.

For recurrent C. difficile infection, FMT and approved products like REBYOTA® represent first-line or second-line treatments with excellent success rates. The evidence is solid, the protocols are established, and insurance increasingly covers the procedures. If you've suffered multiple C. diff recurrences, discussing FMT with your gastroenterologist is not experimental - it's evidence-based medicine.

For inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, the picture is more nuanced. While FMT hasn't proven as consistently effective for IBD as for C. diff, research shows promising results in specific contexts. Some patients experience significant symptom relief, and clinical trials of targeted microbiome therapies are yielding encouraging data. Current IBD treatment guidelines suggest microbiome approaches may become standard adjunct therapies within the next few years.

For autoimmune conditions more broadly, the science is advancing rapidly but hasn't yet translated to approved therapies. Research has identified specific bacterial species and metabolic pathways associated with rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and lupus. A comprehensive synthesis published in 2025 documented the gut microbiome's role in autoimmune disease progression and suggested that restoring microbial balance could modulate immune responses. Clinical trials are underway, but for now, these approaches remain investigational.

For metabolic conditions like obesity and type 2 diabetes, the connection to gut bacteria is clear, but treatments are still emerging. Certain bacterial species produce metabolites that affect insulin sensitivity and fat storage. Some probiotics show modest benefits for weight management and blood sugar control, though results vary significantly between individuals. The heterogeneity suggests what many researchers suspect: microbiome interventions may need to be personalized based on each person's unique microbial profile.

For mental health, we're in the early stages despite intense interest. While studies have associated specific gut bacteria with depression and anxiety, and probiotics marketed as "psychobiotics" claim mood benefits, high-quality clinical evidence remains limited. The gut-brain connection is real, but translating it into reliable treatments requires overcoming significant challenges in study design and individual variability.

While waiting for next-generation therapies to emerge, you're not powerless to support your microbiome. Diet is the most potent tool available. Fiber is the foundation - most Americans consume only about 15 grams daily, while gut bacteria thrive on 25 to 40 grams. Diverse plant foods provide different types of fiber that feed different bacterial species, promoting a diverse and resilient microbiome.

Fermented foods introduce beneficial bacteria directly. Yogurt, kefir, kimchi, sauerkraut, and kombucha contain live cultures that, while they may not permanently colonize your gut, can provide temporary benefits and support existing microbial communities. The key is regular consumption - think of fermented foods as a maintenance dose rather than a one-time treatment.

Probiotics remain controversial. While certain strains have proven benefits for specific conditions - Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG for antibiotic-associated diarrhea, Bifidobacterium infantis for irritable bowel syndrome - most over-the-counter probiotics lack robust clinical evidence. The probiotic market is plagued by products containing dead bacteria, wrong species labels, or insufficient quantities to have effects. If you choose probiotics, select products from reputable manufacturers with published clinical trial data supporting their specific formulations.

Perhaps most important: avoid unnecessary antibiotics. While antibiotics save lives when truly needed, they're prescribed far too often for viral infections they can't treat. Each antibiotic course disrupts your microbiome, sometimes for months. When you do need antibiotics, ask your doctor about probiotic supplementation during and after treatment to help restore microbial balance.

Here's where things get really interesting. The microbiome varies dramatically between individuals - your bacterial profile is as unique as your fingerprint. Two people can eat identical diets and respond completely differently because their gut bacteria process foods in distinct ways. This explains why dietary interventions that work brilliantly for some people fail spectacularly for others.

Microbiome testing companies promise to decode your personal bacterial profile and provide customized dietary recommendations. The science behind this is evolving rapidly. Researchers have developed machine learning algorithms that predict individual responses to foods based on microbiome composition, with some success. Studies show that personalized nutrition plans based on microbiome analysis can improve blood sugar control better than standard dietary advice.

However, the clinical utility of direct-to-consumer microbiome tests remains debated. The tests can tell you which bacteria you harbor, but interpreting what that means for your health is complex and imprecise. The American Gastroenterological Association cautions that microbiome testing shouldn't guide clinical decisions outside of specific research contexts - at least not yet. The technology is advancing fast, though, and personalized microbiome medicine will likely become standard practice within the decade.

Microbiome research reveals fascinating cultural differences. The gut bacteria of people in industrialized nations differ dramatically from those in traditional societies with hunter-gatherer or agricultural lifestyles. Modern Western microbiomes are generally less diverse, lacking bacterial species common in populations with more fiber-rich diets and lower antibiotic exposure.

This has sparked debate about "rewilding" the microbiome - deliberately reintroducing bacterial species lost during modernization. Some researchers are studying microbiomes of isolated populations to identify beneficial bacteria that could be reintroduced to Westerners. Others are exploring whether the hygiene hypothesis - the idea that excessive cleanliness contributes to allergies and autoimmune diseases - might be addressed through controlled microbial exposure.

The regulatory landscape is evolving globally. Europe, the United States, and Asia are developing frameworks for approving microbiome therapies, though approaches differ. The U.S. FDA initially regulated FMT as an investigational drug but has shown flexibility as the field matures. As of 2025, regulatory momentum is building, with clearer pathways emerging for live biotherapeutic products.

For all its promise, microbiome medicine raises significant concerns. FMT, while generally safe, has transmitted infections in rare cases, including one that proved fatal. This underscores the need for rigorous donor screening and quality control. Long-term effects of microbiome manipulation remain largely unknown - we're editing an ecosystem we don't fully understand.

There are equity issues too. Advanced microbiome therapies will likely be expensive, at least initially, potentially creating a divide between those who can afford cutting-edge treatments and those who can't. Access to healthy donors for FMT is geographically uneven, and commercial products may not reach underserved communities.

The commercialization of microbiome science has spawned a cottage industry of exaggerated claims. Probiotic supplements, microbiome tests, and dietary products often promise far more than evidence supports. Distinguishing legitimate science from marketing hype requires critical thinking and medical literacy that many patients lack.

Perhaps most profoundly, microbiome medicine forces us to reconceptualize what it means to be human. We're not autonomous individuals but rather ecosystems - superorganisms composed of human and microbial cells working in concert. This challenges notions of biological identity and raises philosophical questions about intervention. If our bacteria influence our thoughts and moods, who are we really?

The next decade will likely bring microbiome therapies for conditions currently treated with immunosuppressants, antidepressants, and metabolic drugs. Imagine a future where instead of lifelong medications with significant side effects, you receive a one-time or periodic microbial therapy that resets your gut ecosystem to a healthy state. For some conditions, that future is already arriving.

Research priorities are shifting toward understanding which bacterial species and metabolic pathways are truly causative versus merely associated with disease. Scientists are developing more sophisticated tools to monitor microbiome changes in real-time and predict therapeutic responses. Machine learning is accelerating the discovery of bacterial combinations optimized for specific outcomes.

The convergence of microbiome science with other fields - genomics, metabolomics, immunology, neuroscience - is creating a more holistic understanding of human health. We're moving from reductionist medicine that treats symptoms in isolation toward systems medicine that addresses root causes in interconnected biological networks.

For clinicians, staying current with microbiome research is becoming essential. The field is moving fast, and treatments considered experimental today may be standard practice tomorrow. Medical education is beginning to incorporate microbiome science, but most practicing physicians need continuing education to integrate these advances into patient care.

For patients, the message is one of cautious optimism. The microbiome revolution is real, not hype, but it's also not a panacea. Support your gut bacteria through diet and lifestyle. Be skeptical of exaggerated commercial claims. Stay informed about emerging therapies. And most importantly, maintain open communication with healthcare providers who can help you navigate this rapidly evolving landscape.

The journey from recognizing gut bacteria as important to treating diseases by manipulating microbial ecosystems represents one of medicine's most profound shifts. We're still in the early chapters of this story, but the trajectory is clear: the microbes within us are no longer medical afterthoughts but central players in health and disease. Learning to work with them, rather than simply trying to eliminate the bad ones, may be the key to preventing and treating conditions that have plagued humanity for millennia.

What once seemed like science fiction - designer bacteria engineered to prevent cancer, mood disorders treated with microbial cocktails, personalized nutrition plans based on your unique bacterial profile - is becoming medical fact. The revolution is underway, and it's happening in the most unlikely of places: your gut.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

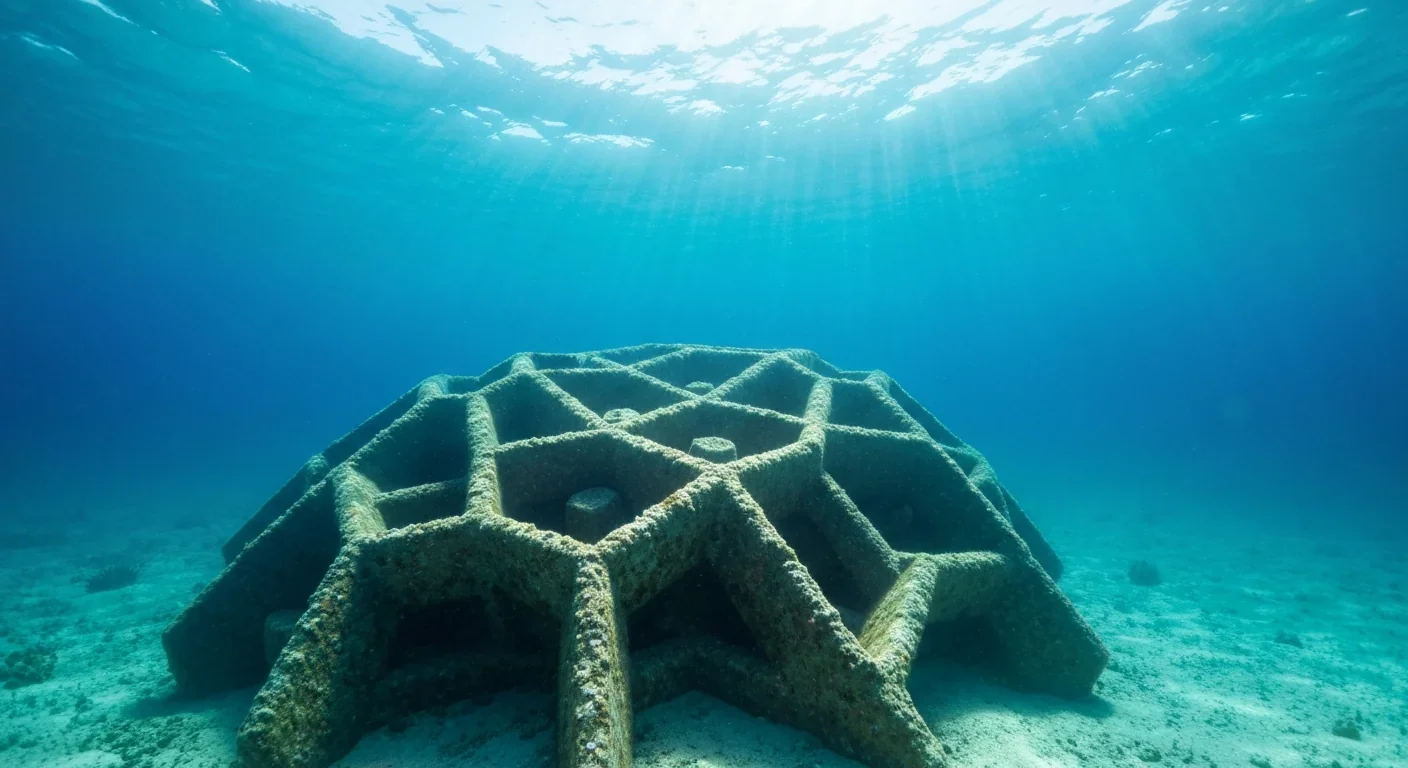

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

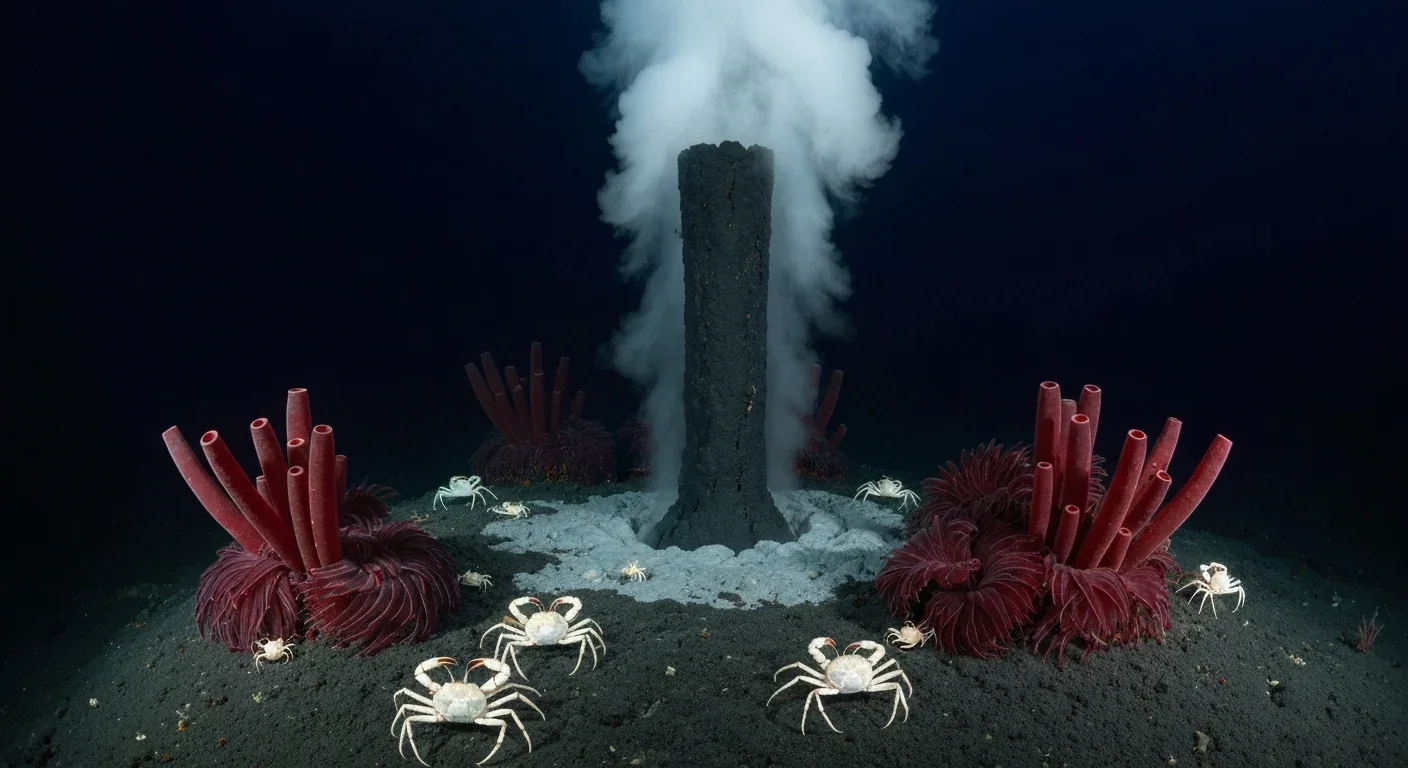

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

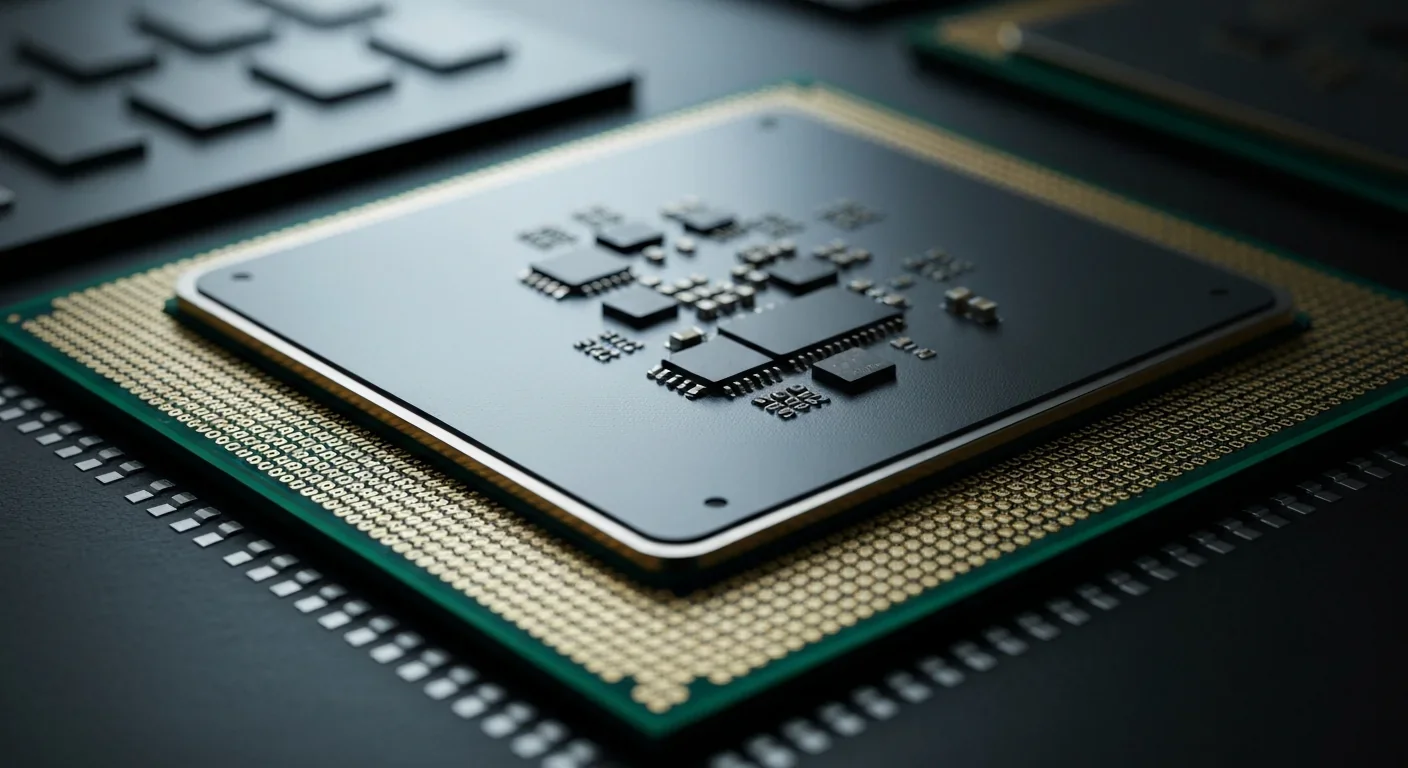

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.