Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: Agricultural pesticides drift miles from application sites through wind and volatilization, contaminating water supplies, communities, and ecosystems. Recent studies link exposure to childhood cancers and health impacts, while legal battles reveal regulatory gaps and economic pressures driving intensive chemical use.

On a warm August morning in 2017, Missouri peach farmer Bill Bader walked into his orchard and found devastation. Thirty thousand trees, representing decades of work, stood withered and dying. The culprit wasn't disease or drought - it was dicamba, an herbicide that had drifted from neighboring soybean fields miles away. By 2020, Bader won a landmark $265 million verdict against Monsanto and BASF, but his trees were gone forever. His story is not unique. It's a window into a largely invisible environmental crisis unfolding across agricultural regions worldwide.

Pesticide drift - the unintentional movement of agricultural chemicals beyond their target areas - represents one of the most pressing yet underreported threats to environmental and public health today. These chemicals don't simply disappear after application. They become airborne vapors that ride wind currents for miles, seep into groundwater systems, and contaminate distant communities, water supplies, and ecosystems. Recent research reveals the problem is far more extensive than previously understood, affecting everything from childhood cancer rates to drinking water safety in communities that may not even realize they're at risk.

Pesticides travel through two primary mechanisms: physical spray drift and chemical volatilization. Physical drift occurs when tiny droplets become airborne during application, carried away by wind. But volatilization is more insidious. Certain herbicides, particularly dicamba, evaporate from treated surfaces and form chemical clouds that drift unpredictably across landscapes.

Temperature and humidity dramatically amplify this effect. Under hot, humid conditions, dicamba volatilizes rapidly, creating vapor clouds that can travel several miles from the application site. The chemical can re-deposit days after the initial spraying, contaminating crops, gardens, and wild vegetation far from any farm.

Wind speed, direction, and atmospheric stability all influence how far pesticides travel. Studies show that even under ideal application conditions, spray droplets smaller than 150 microns - roughly the width of a human hair - can remain suspended in air for extended periods, drifting substantial distances before settling. During ultra-low volume spraying, wind drift becomes an intentional dispersal mechanism, though one that's difficult to contain within target boundaries.

The persistence of these chemicals compounds the problem. Glyphosate, the world's most widely used herbicide, has a soil half-life ranging from two to 197 days depending on environmental conditions. In Texas, it degrades in as little as three days; in Iowa, it persists for 142 days. This variability means drift contamination in some regions creates long-term exposure risks.

Water provides another crucial transport pathway. Agricultural runoff carries pesticides into streams, rivers, and groundwater. A U.S. Geological Survey study found glyphosate present in 90% of monitored streams downstream from agricultural operations. Once in water, glyphosate remains stable and doesn't degrade easily, allowing it to accumulate and travel through watershed systems.

The contamination of drinking water supplies represents one of drift's most alarming consequences. In Florida, one drinking water facility recorded glyphosate levels of 9.00 parts per billion (ppb). In Louisiana, two facilities measured 8.35 ppb and 5.05 ppb - all exceeding the Environmental Working Group's health-based recommendation of 5 ppb, though well below the EPA's legal limit of 700 ppb.

The wide gap between advocacy group recommendations and regulatory limits reflects ongoing scientific debate about safe exposure levels. But the presence of agricultural chemicals in tap water miles from any farm demonstrates how effectively drift contaminates water systems.

Dicamba presents particularly troubling water contamination patterns. Though poorly soluble in water, a 1991-1996 USGS study detected dicamba in 0.13% of surveyed groundwater samples, with maximum concentrations reaching 0.0021 milligrams per liter. These seemingly small percentages translate to widespread potential exposure when considering the millions who rely on groundwater for drinking water.

The chemicals don't travel alone. Commercial pesticide formulations contain adjuvants - additional compounds that enhance effectiveness. Glyphosate formulations often include polyoxyethylene amine (POEA), a surfactant significantly more toxic to aquatic organisms than glyphosate itself. When drift delivers these formulations to waterways, the ecological damage exceeds what the active ingredient alone would cause.

Perhaps nowhere is pesticide drift's human cost more evident than in California's Central Valley, where intensive agriculture meets dense suburban development. A 2025 study published in Environmental Research examined data from more than 200,000 California births between 1998 and 2016, including 199 children diagnosed with neuroblastoma - a rare but often deadly childhood cancer.

The findings were striking. Prenatal exposure to flonicamid, cypermethrin, permethrin, and benomyl was associated with a 33%, 53%, 24%, and 20% increased neuroblastoma risk, respectively, compared to babies with no estimated exposure. "Just knowing the pesticides broadly might be linked to cancer doesn't provide an actionable strategy," explained Julia Heck, the study's senior author from the University of North Texas. "We wanted to know which are the bad actors."

The benomyl finding is particularly concerning. The EPA banned this fungicide in 2001, yet the study found continued elevated cancer risk in children born near former application sites over a decade later, demonstrating how legacy pesticides can persist in soil and continue affecting communities long after regulatory action.

Agricultural workers face the most direct exposure. From 1998 to 2006, Environmental Health Perspectives documented nearly 3,000 cases of pesticide drift exposure. Nearly half involved workers in treated fields, and 14% were children under age 15. These numbers likely represent significant underreporting, as many affected individuals lack access to medical care or fear retaliation for reporting exposure.

The health effects extend beyond cancer. Studies have linked dicamba exposure to increased risk of liver and bile duct cancers. The NIH's Agricultural Health Study reported elevated lung and colon cancer rates among those exposed to dicamba, with clear dose-response patterns suggesting causation rather than coincidence.

Vulnerable populations bear disproportionate risk. Children's developing bodies are particularly susceptible to chemical exposure. Pregnant women living near agricultural areas risk exposing their fetuses during critical developmental windows. Low-income communities often cluster near agricultural zones due to housing affordability, creating environmental justice concerns where those with fewest resources face greatest exposure.

Understanding why pesticide drift persists requires examining the economic forces driving intensive chemical use. The introduction of genetically modified dicamba-resistant crops in 2016 triggered an explosion in herbicide application. Dicamba use jumped from 8 million pounds in 2016 to 30 million pounds by 2019 - a nearly fourfold increase in just three years.

This surge wasn't accidental. Monsanto (now Bayer) developed both the dicamba-resistant soybean seeds and the herbicide to spray on them, creating a closed loop where farmers who adopted the GM seeds had strong incentives to use more dicamba. Neighboring farmers then faced pressure to adopt the same system or risk crop damage from drift.

The economic calculus is brutal. Industrial-scale agriculture operates on thin profit margins, with success measured in yield per acre. Pesticides offer cheap, effective weed and pest control compared to labor-intensive mechanical or organic methods. A farmer who reduces chemical use may see yields drop, placing them at competitive disadvantage.

But the external costs are enormous. The damage to neighboring crops, wild ecosystems, water quality, and human health doesn't appear on any farm's balance sheet. Society bears these costs through healthcare expenses, environmental remediation, property devaluation, and diminished quality of life in affected communities.

Between 2016 and 2019, U.S. dicamba use increased nearly 400% - from 8 million to 30 million pounds annually - following the approval of dicamba-resistant GMO crops.

Legal battles over pesticide drift reveal both the scale of damage and the challenges of obtaining justice. The Bader family's case against Monsanto and BASF set precedents. After their 30,000 peach trees died from dicamba drift, they filed suit. The jury awarded $15 million in actual damages and $250 million in punitive damages - a clear signal that manufacturers bore responsibility for products they knew would drift.

That verdict was just the beginning. By 2020, Monsanto and BASF faced a nationwide multidistrict litigation with hundreds of similar claims. The companies eventually reached a $400 million settlement, though they admitted no wrongdoing.

These legal victories matter, but they come too late for many farmers. Proving causation requires expensive expert testimony. Documentation must link specific applications to specific damage. Many small farmers lack resources for extended litigation against agrochemical giants with vast legal budgets.

The litigation also reveals manufacturer knowledge. Internal documents show companies understood drift risks but promoted products anyway. They developed "low-volatility" formulations that still volatilized significantly under field conditions. Application instructions proved impractical for real-world farming operations, where weather windows for spraying are limited.

Arkansas and Missouri, facing widespread crop damage, took the extraordinary step of temporarily banning dicamba use during growing seasons. These state-level interventions acknowledged that voluntary compliance and label restrictions weren't preventing drift damage.

Federal pesticide regulation in the United States falls primarily to the EPA, which faces a difficult balancing act. The agency must weigh agricultural productivity, chemical company interests, environmental protection, and public health - often with incomplete data and under political pressure.

The EPA's dicamba saga illustrates regulatory challenges. In 2016, the agency approved dicamba for use on genetically modified crops. By 2017, widespread drift damage led to criminal investigations into illegal use of older, more drift-prone formulations. In 2020, a federal court vacated EPA approval of three dicamba products, finding the agency had "substantially understated" drift risks. The EPA then reauthorized modified formulations with additional restrictions.

This regulatory whiplash creates uncertainty for farmers while failing to prevent damage. Label requirements - such as avoiding application on high-temperature days - sound reasonable but prove difficult to enforce. How does anyone verify that thousands of farmers across millions of acres are following application timing rules?

Buffer zones represent another regulatory tool with mixed effectiveness. Pesticide labels may require specific distances between application areas and sensitive sites like schools, homes, or waterways. But volatilization makes such buffers less effective than for purely physical drift. A chemical that evaporates and reforms miles away isn't stopped by a 100-foot buffer.

The contrast between the EPA's legal limits and health advocates' recommendations highlights scientific uncertainty. The EPA sets glyphosate's maximum contaminant level at 700 ppb for drinking water, while the Environmental Working Group recommends 5 ppb based on California's Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment findings. This 140-fold difference reflects disagreement about long-term, low-level exposure risks.

"There are bans, pests become resistant, pesticide companies come out with new formulations. It's hard to stay on top of something that changes so fast."

- Dr. Julia Heck, University of North Texas

Internationally, regulatory approaches vary widely. The European Union has taken more precautionary stances, banning certain pesticides approved in the United States. Some nations require greater buffer zones or restrict aerial application. But in a globalized food system, stringent regulations in one country may simply shift production to regions with laxer standards.

Solutions exist, though none are perfect. Drift retardants - compounds like polyacrylamide added to spray mixtures - suppress formation of tiny droplets most prone to drift. These additives increase droplet size and weight, causing pesticides to fall closer to target areas.

However, retardants don't address volatilization. A larger droplet that doesn't drift initially can still evaporate days later when temperatures rise, creating secondary drift events. For chemicals like dicamba, drift retardants provide only partial solutions.

Application technology matters significantly. Older boom sprayers with high-pressure nozzles create fine mists that drift easily. Modern low-drift nozzles produce larger, more uniform droplets. Spray shields and shrouds physically contain chemicals during application. These technologies reduce but don't eliminate drift risk.

Timing applications correctly can dramatically decrease drift. Spraying during cool, calm conditions with moderate humidity minimizes both physical drift and volatilization. But farmers face narrow windows for pesticide application, often during critical growth stages or when weather forecasts show limited suitable days. Economic pressure to treat fields promptly can override drift-prevention best practices.

Precision agriculture technologies offer new approaches. GPS-guided equipment can map field boundaries precisely, reducing overspray at edges. Weather monitoring systems can alert farmers to high-drift conditions. Some advanced systems adjust application rates in real-time based on environmental factors.

Windbreaks - rows of trees or shrubs between fields and sensitive areas - provide physical barriers to drift. Research shows strategically placed vegetation can reduce pesticide deposition in adjacent areas by 50% or more. But establishing windbreaks requires land, time, and maintenance, and they're impractical in areas with large, contiguous monoculture operations.

Integrated pest management (IPM) emphasizes prevention, monitoring, and using multiple control tactics to reduce pesticide dependence. Crop rotation, cover cropping, biological controls, and selective pesticide use when necessary can maintain yields while reducing overall chemical inputs. But IPM requires more knowledge, labor, and upfront investment than conventional spray-and-pray approaches.

Affected communities aren't waiting for regulatory solutions. In California's Central Valley, resident groups have organized air quality monitoring networks to track pesticide levels near schools and homes. These community science efforts fill gaps in official monitoring and provide data for advocacy.

Education campaigns help residents understand exposure risks and protective measures. Simple actions - closing windows during spraying season, washing produce thoroughly, using air filters - can reduce household exposure. Schools in agricultural areas have developed notification systems alerting parents when nearby applications are scheduled.

Some communities are pursuing local ordinances to restrict pesticide use near sensitive sites like schools and healthcare facilities. These local regulations often face legal challenges from agricultural interests and state preemption laws, but they demonstrate grassroots demand for protection.

Organic farmers and conventional farmers facing drift damage have formed unlikely alliances. Both groups want stricter drift prevention measures, though their ultimate goals may differ. These coalitions carry political weight that neither group achieves alone.

Legal aid organizations have helped farmworkers and rural residents pursue compensation for drift-related health impacts. Though individual cases rarely yield large settlements, pattern-and-practice litigation can pressure manufacturers and large agricultural operators to change practices.

Environmental justice advocates highlight how pesticide drift disproportionately affects Latino communities in agricultural regions. This framing connects drift issues to broader civil rights concerns, potentially broadening political support for stronger protections.

Addressing pesticide drift requires systemic changes across multiple domains. Regulatory reform should strengthen drift risk assessment before approving new pesticides, increase buffer zone requirements near sensitive areas, and enhance monitoring and enforcement. The California Department of Pesticide Regulation's air monitoring program, while imperfect, provides a model for tracking actual exposure levels rather than relying on application data alone.

Agricultural policy should incentivize drift-reducing practices through crop insurance discounts, cost-share programs for low-drift equipment, and technical assistance for farmers transitioning to integrated pest management. Market-based approaches - such as pesticide taxes that internalize external costs - could shift economic calculus toward less-toxic alternatives.

Research priorities should include developing less volatile pesticide formulations, improving drift prediction models, and conducting long-term health studies in exposed communities. The lag between benomyl's 2001 ban and continued health impacts two decades later underscores how little we understand about persistent environmental contamination.

Transparency measures would empower affected communities. Publicly accessible databases showing pesticide applications by location, chemical, and timing would allow residents to connect exposure to health outcomes. Real-time alert systems could notify communities of nearby applications, enabling protective actions.

Consumer pressure matters too. Demand for organic produce and sustainably farmed food can shift agricultural practices by making lower-pesticide production economically viable. But this works only if organic and sustainable options remain affordable and accessible across income levels.

"Just knowing the pesticides broadly might be linked to cancer doesn't provide an actionable strategy. We wanted to know which are the bad actors."

- Dr. Julia Heck, University of North Texas

Ultimately, the pesticide drift crisis reflects deeper tensions in modern agriculture. We've built food systems that demand ever-higher yields from ever-larger monocultures, with chemicals providing the simplest path to that productivity. Unwinding this system requires rethinking not just pesticide policy but farm economics, land use, agricultural research priorities, and even what we expect from our food system.

The invisible chemical clouds drifting from farm fields represent externalized costs of cheap, abundant food. Making those costs visible - through regulation, litigation, community action, and market forces - may finally create pressure for fundamental change. Bill Bader's devastated peach orchard stands as testament to what happens when we ignore the problem. The question is whether we'll act before the damage becomes irreversible.

For communities concerned about pesticide drift exposure, resources include state pesticide regulatory agencies, local health departments, environmental advocacy groups, and legal services organizations specializing in environmental justice. The National Pesticide Information Center offers science-based information about pesticide risks and exposure reduction. As awareness grows, so does the possibility of meaningful change - but only if we refuse to accept invisible threats as inevitable costs of modern agriculture.

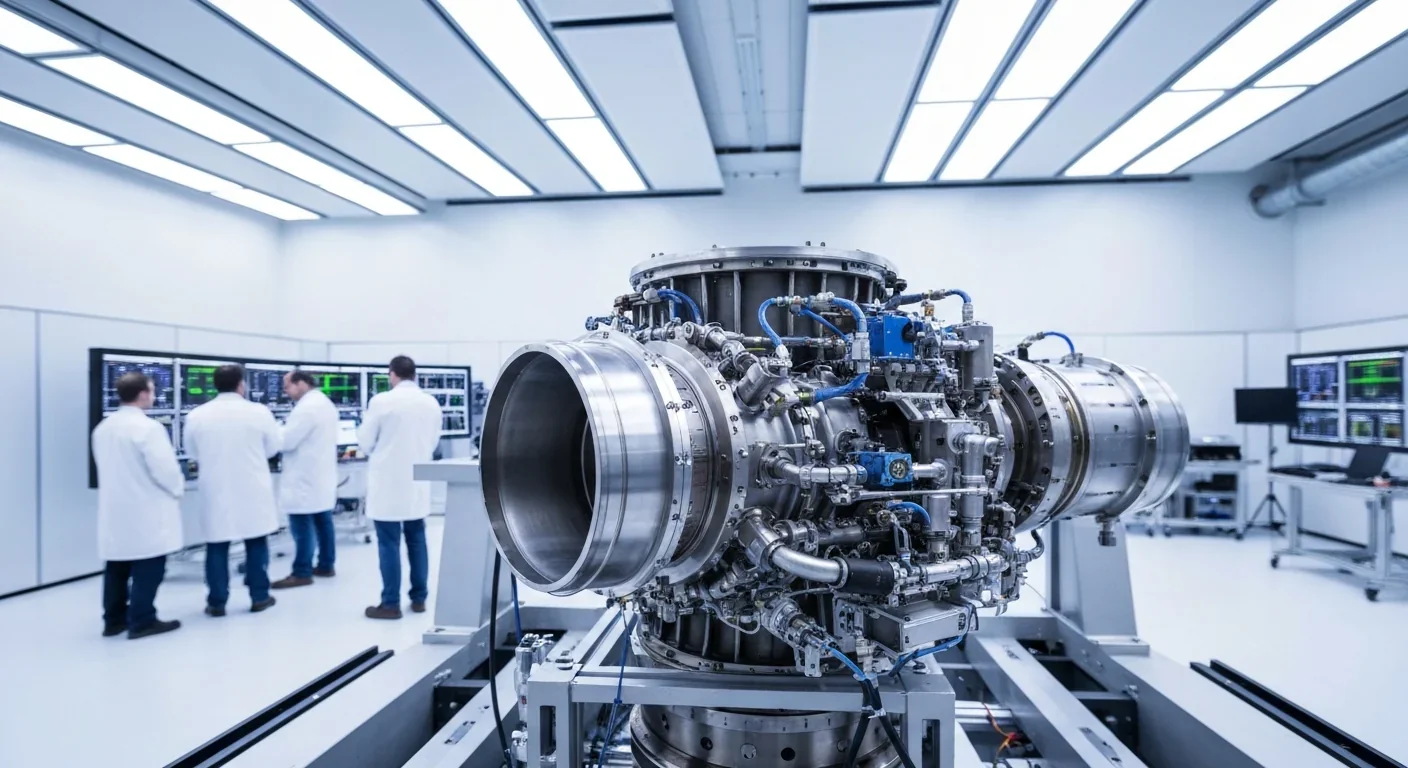

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

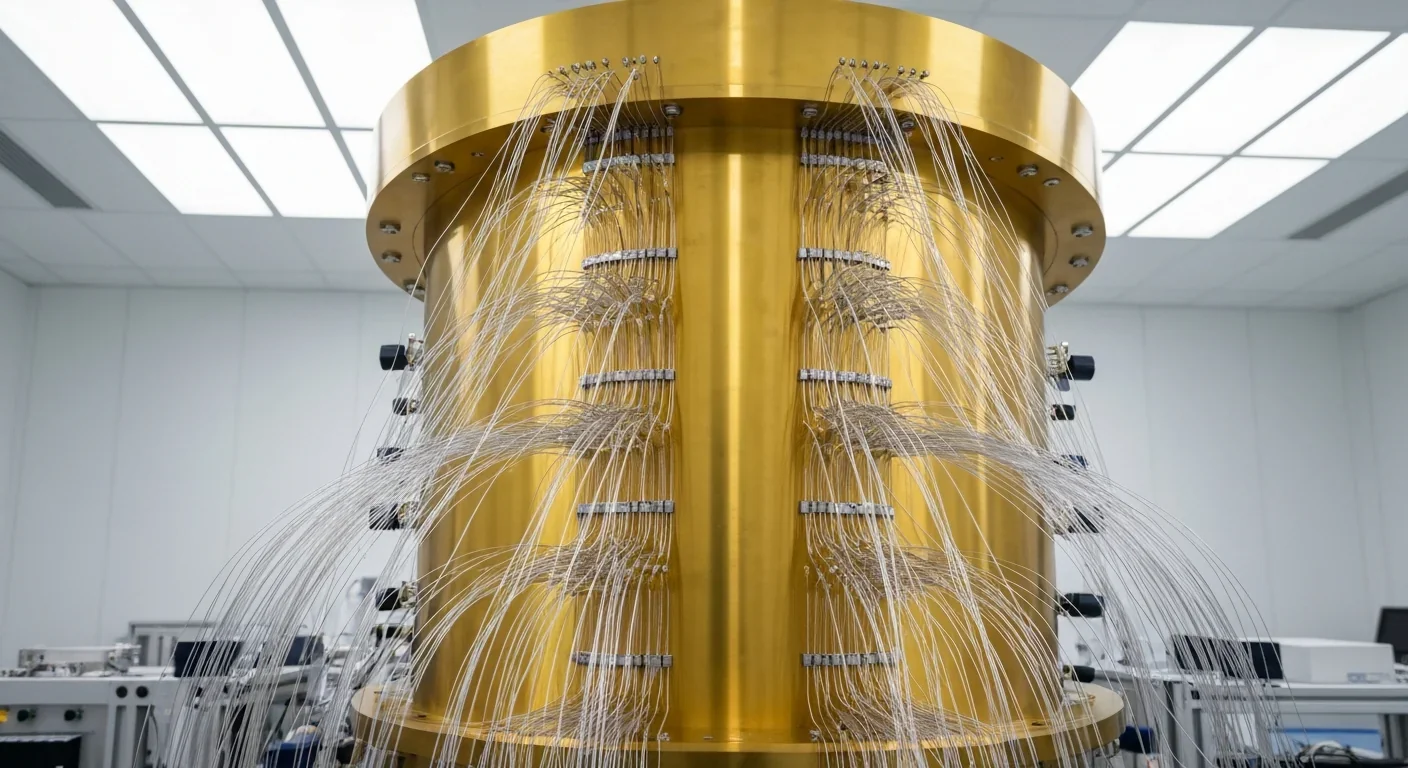

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.