Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: Nitrites in processed meats convert to N-nitroso compounds in your gut, directly damaging DNA and increasing cancer risk. Learn the biochemical mechanisms, which meats pose the highest risk, and evidence-based strategies to protect yourself.

The hot dog at your child's baseball game, the bacon on your breakfast plate, the deli meat in your sandwich - these everyday foods harbor a biochemical time bomb that most consumers never see coming. Inside your digestive system, the same preservatives that keep these meats fresh and pink are quietly converting into compounds that directly attack your DNA, setting the stage for cancer years or decades down the road.

This isn't speculation or fear-mongering. In 2015, the World Health Organization classified processed meat as a Group 1 carcinogen, placing it in the same category as tobacco and asbestos. Behind this classification lies a specific biochemical villain: N-nitroso compounds, or NOCs, formed when the nitrites in your bacon meet the proteins in your gut.

For over a century, food manufacturers have relied on sodium nitrite to preserve meat. It performs three crucial jobs: preventing deadly botulism bacteria, maintaining the appetizing pink color consumers expect, and adding that distinctive cured flavor. Without nitrites, your deli ham would be gray, your hot dogs would spoil within days, and outbreaks of botulism poisoning would return.

But this preservation comes at a cost. When you consume processed meats containing nitrites, your body becomes a chemical reactor where these preservatives undergo a dangerous transformation.

The process begins in your stomach, where the acidic environment converts nitrites into nitrous acid. This reactive molecule then encounters amino acids and amines from the digested meat protein. Through a process called nitrosation, they combine to form N-nitroso compounds - powerful alkylating agents that can modify the molecular structure of DNA itself.

The damage N-nitroso compounds inflict on DNA is both specific and insidious. These molecules don't just break DNA strands randomly; they chemically modify the guanine bases that form one of DNA's four building blocks. The most concerning modification is called O6-alkylguanine, where an alkyl group attaches to the oxygen atom at the sixth position of the guanine molecule.

This might sound like molecular minutiae, but this single change has profound consequences. When cells attempt to replicate DNA containing O6-alkylguanine adducts, the cellular machinery misreads the modified base. Instead of pairing guanine with cytosine as it should, the replication machinery pairs it with thymine. This creates a point mutation - a permanent change in the genetic code.

Your cells contain a repair protein called MGMT that works like a molecular suicide bomber - it fixes one DNA lesion, then destroys itself. With repeated processed meat consumption, DNA damage can outpace your body's repair capacity.

Your cells have evolved a sophisticated repair protein called O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase (MGMT) specifically to fix this type of damage. The MGMT enzyme works like a molecular suicide bomber, transferring the alkyl group from the damaged DNA onto itself, which permanently inactivates the enzyme. Each MGMT molecule can only repair one DNA lesion before it's destroyed.

The problem emerges when exposure to N-nitroso compounds exceeds your cellular repair capacity. With repeated consumption of processed meats, the formation of O6-alkylguanine adducts can outpace your body's ability to fix them. Unrepaired lesions accumulate, particularly in the rapidly dividing cells of your intestinal lining, where they trigger mutations in genes that normally prevent cancer.

The link between processed meat and cancer isn't theoretical. A comprehensive 2015 meta-analysis involving over 1.2 million people found that each additional 50 grams of processed meat consumed per day increases colorectal cancer risk by 18 percent. That's roughly one hot dog or a few slices of deli meat.

To put this in perspective, if you consume a typical serving of processed meat daily, your lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer rises from about 5 percent to nearly 6 percent. While this might seem modest, across populations it translates to tens of thousands of additional cancer cases annually.

The intestinal tract bears the brunt because it's ground zero for NOC formation and exposure. As processed meat moves through your digestive system, the continuous chemical reaction between nitrites and amino acids creates a sustained exposure to DNA-damaging compounds. Intestinal cells, which normally divide every few days to replace the gut lining, become particularly vulnerable. With each division, unrepaired DNA damage can become locked into the genetic code of daughter cells.

But colorectal cancer isn't the only concern. Research has linked processed meat consumption to elevated risks of stomach, pancreatic, and even breast cancers, though the evidence is strongest for cancers of the digestive tract where NOC exposure is most direct.

Here's something most consumers don't realize: the cancer risk from processed meats varies dramatically depending on which type you choose. Bacon and hot dogs contain the highest levels of residual nitrites among common processed meats, making them the most problematic choices.

This variation stems from differences in curing processes and meat composition. Bacon typically requires higher nitrite concentrations to achieve the flavor and color consumers expect. Hot dogs, made from finely ground meat with high surface area, also tend to retain more nitrites. Meanwhile, some European-style sausages and traditionally cured meats use different preservation methods or lower nitrite levels.

"Each additional 50 grams of processed meat consumed per day results in an 18% increased risk of colorectal cancer - that's roughly one hot dog or a few slices of deli meat."

- 2015 Meta-Analysis, 1.2 Million Participants

The concentration of heme iron also matters. Heme, the iron-containing molecule in red blood cells, catalyzes the formation of NOCs, making red meat-based processed products more carcinogenic than those made from poultry. This is why turkey bacon, while not risk-free, poses a lower threat than traditional pork bacon.

Cooking method amplifies the problem. High-temperature cooking, particularly grilling or frying, accelerates NOC formation. That crispy, charred bacon you love? It's swimming in N-nitroso compounds. Gentler cooking methods like baking at lower temperatures can reduce but not eliminate NOC formation.

Food safety regulators worldwide face a genuine dilemma: nitrites prevent botulism, a potentially lethal foodborne illness, but they also contribute to cancer risk. It's a classic example of trading one health threat for another, and different countries have reached different conclusions.

In the European Union, recent regulations have tightened limits on nitrite use in processed meats, particularly for products targeting children. Some member states are exploring mandatory nitrite reduction targets, with France leading efforts to halve nitrite levels in processed meats by 2025. The UK's Food Standards Agency has advocated for stricter controls on nitrite use, though industry resistance remains strong.

The United States has taken a more conservative approach. The FDA permits nitrite levels up to 156 parts per million in finished products, though most manufacturers use lower amounts. The agency argues that when used at approved levels with ascorbic acid (which inhibits NOC formation), the botulism prevention benefits outweigh cancer risks.

Consumer advocacy groups counter that this risk-benefit calculation doesn't adequately account for chronic, long-term exposure across a lifetime. They point to Scandinavian countries where stricter limits haven't led to botulism outbreaks, suggesting that lower nitrite levels are both feasible and safer.

The "nitrite-free" label on some processed meats adds another layer of confusion. These products often use celery powder or celery juice, which naturally contain high concentrations of nitrates. Bacteria convert these nitrates to nitrites during processing, meaning "uncured" or "no nitrites added" products can contain similar or even higher nitrite levels than conventionally cured meats. Yet they legally qualify for these misleading labels.

The processed meat industry's reliance on nitrites reflects a century-old bargain between immediate and delayed health risks. In the early 1900s, before widespread refrigeration, botulism poisoning killed thousands annually. Canning and curing with nitrites eliminated this immediate threat, making processed meats safe to store and transport.

For decades, this seemed like an unambiguous victory for public health. Only in the 1970s did researchers discover that nitrites could form carcinogenic NOCs, particularly during cooking. Even then, the cancer risk appeared abstract and distant compared to the immediate danger of botulism.

When processed meat was an occasional treat, cancer risk remained marginal. But with Americans now consuming over 18 pounds of bacon and 18 pounds of hot dogs annually, the population-level cancer burden has grown substantially.

This mirrors other public health trade-offs throughout history. We chlorinate water to prevent cholera, despite trace carcinogens formed by chlorination. We pasteurize milk to kill pathogens, despite modest nutrient losses. In each case, regulators concluded that preventing acute disease justified accepting small increases in chronic disease risk.

What's changed is our understanding of cumulative exposure. When processed meat was an occasional treat, the cancer risk remained marginal. But as these products became dietary staples - with the average American consuming over 18 pounds of bacon and 18 pounds of hot dogs annually - the population-level cancer burden has grown substantially.

Your body isn't defenseless against NOC damage. Beyond the MGMT repair enzyme, several other protective mechanisms exist. Vitamin C and other antioxidants can intercept nitrites before they form NOCs, which is why food manufacturers often add ascorbic acid to cured meats.

Consuming vitamin C-rich foods alongside processed meats offers similar protection. A glass of orange juice with your bacon or tomatoes on your sandwich can significantly reduce NOC formation in your stomach. The vitamin C donates electrons to nitrous acid, converting it back to harmless nitric oxide before it can react with amino acids.

Other dietary factors influence NOC formation and DNA repair capacity. Fiber speeds intestinal transit time, reducing exposure duration. Phytochemicals in vegetables can enhance DNA repair mechanisms. This helps explain why individuals who consume processed meats as part of an otherwise healthy, plant-rich diet show lower cancer risks than those eating processed meats with few protective foods.

Your genetic makeup also plays a role. Some people inherit more efficient versions of the MGMT repair enzyme, while others have genetic variants that process carcinogens more slowly. This genetic variation means identical processed meat consumption can produce different cancer risks in different individuals. Population-level statistics reflect averages, but your personal risk depends on your unique genetic and dietary profile.

The scientific community continues refining our understanding of how processed meats damage DNA. Recent research has identified specific molecular signatures of NOC-induced mutations in colorectal tumors, providing direct evidence that dietary NOCs contribute to human cancers, not just laboratory animals.

Advanced analytical techniques now allow researchers to measure NOC levels directly in human tissues after processed meat consumption. These studies reveal that NOC concentrations in the intestinal lining can reach levels sufficient to cause DNA damage within hours of eating bacon or hot dogs.

The food industry is exploring alternatives to traditional nitrite curing. Some companies are developing starter cultures of beneficial bacteria that inhibit pathogens without nitrites. Others are experimenting with natural antimicrobials derived from plants. Vacuum packaging and modified atmosphere technology can extend shelf life without chemical preservatives.

However, replicating the flavor and appearance consumers expect from processed meats remains challenging. Decades of marketing have conditioned people to associate the pink color and distinctive taste of nitrite-cured meat with quality and freshness. Products that look or taste different struggle in the marketplace, even when they're healthier.

One promising approach involves encapsulating nitrites in ways that prevent their release until after the product has been safely preserved, but before it's consumed. This could maintain food safety while reducing NOC formation in the body. Clinical trials of such technologies are ongoing.

Understanding the science behind processed meat carcinogens empowers you to make informed choices. Here's practical guidance based on current evidence:

First, recognize that processed meat should be an occasional indulgence, not a dietary staple. The American Institute for Cancer Research recommends avoiding processed meat entirely or limiting consumption to special occasions.

When you do consume processed meat, choose products with lower nitrite content. Look for European-style cured meats or products from manufacturers committed to nitrite reduction. While "uncured" labels can be misleading, some brands genuinely use lower-risk preservation methods.

"A glass of orange juice with your bacon or tomatoes on your sandwich can significantly reduce N-nitroso compound formation in your stomach. The vitamin C intercepts nitrites before they can damage DNA."

- Research on Antioxidant Protection

Always pair processed meats with vitamin C-rich foods. Add peppers, tomatoes, or citrus to meals containing bacon or deli meat. This simple habit can reduce NOC formation significantly.

Cook processed meats gently. Avoid charring or high-temperature frying. Baking or steaming causes less NOC formation than grilling or pan-frying at high heat.

Balance your diet with protective foods. High-fiber vegetables, whole grains, and foods rich in antioxidants enhance your body's DNA repair capacity. A diet rich in these foods can offset some of the risks from occasional processed meat consumption.

Consider alternatives. Many plant-based meat substitutes now replicate the taste and texture of processed meats without nitrites or heme iron. While they're not perfect nutritionally, they eliminate the specific DNA damage mechanisms we've discussed.

Stay informed about emerging regulations and food industry innovations. As consumer awareness grows and technology advances, safer processed meat options will become more available.

The processed meat controversy exemplifies a broader challenge in modern nutrition: many of our food-related health risks emerge from chronic, low-level exposures rather than acute poisoning. The cancer risk from any single serving of bacon is infinitesimal, but the cumulative impact over a lifetime can be substantial.

This makes personal risk assessment difficult. Unlike smoking, where the link to lung cancer is dramatic and immediate, the connection between processed meat and colorectal cancer unfolds over decades. The time lag between exposure and disease obscures the causal relationship for individual consumers.

It also complicates public health messaging. Telling people to avoid bacon entirely feels extreme when individual servings pose minimal risk. Yet from a population perspective, widespread processed meat consumption contributes thousands of preventable cancer cases annually.

The solution likely requires both individual action and systemic change. On a personal level, understanding the biochemical mechanisms involved empowers you to make informed trade-offs. Maybe you decide the occasional hot dog at a baseball game is worth the minimal risk, while eliminating daily bacon becomes a priority.

Systemically, we need continued pressure on food manufacturers to develop genuinely safer preservation methods and on regulators to tighten standards as technology advances. The current regulatory framework, developed when processed meat was consumed less frequently, needs updating for our current dietary reality.

The story of N-nitroso compounds and DNA damage isn't finished. As research techniques grow more sophisticated, we're likely to discover additional mechanisms by which processed meats influence cancer risk. We may also identify genetic markers that help predict individual susceptibility, enabling more personalized dietary guidance.

Meanwhile, the tension between food safety, consumer preference, and long-term health will continue. Nitrites prevent immediate, visible harm (botulism) while contributing to delayed, invisible harm (cancer). Our food system and regulatory structure struggle with this temporal mismatch.

What's clear is that the cancer risk from processed meat is real, mechanistically understood, and entirely preventable. The DNA damage caused by N-nitroso compounds isn't hypothetical or controversial - it's basic biochemistry, observed in laboratory studies and confirmed in human populations.

You can't eliminate all cancer risk, and dietary choices involve countless trade-offs. But armed with understanding of how meat preservatives transform into DNA-damaging compounds in your gut, you can make choices that align with your health priorities. The hot dog will still be there for special occasions. Your DNA will thank you for making them special again.

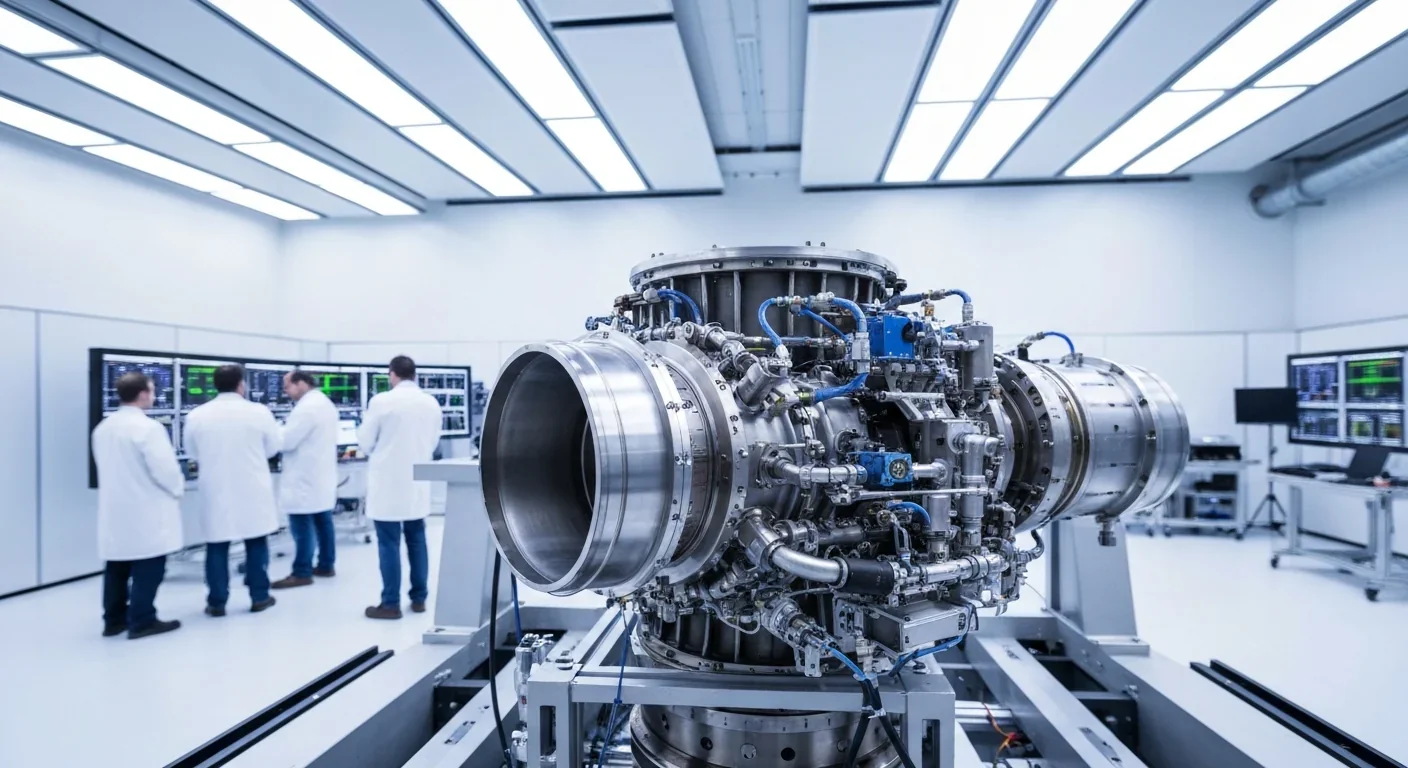

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

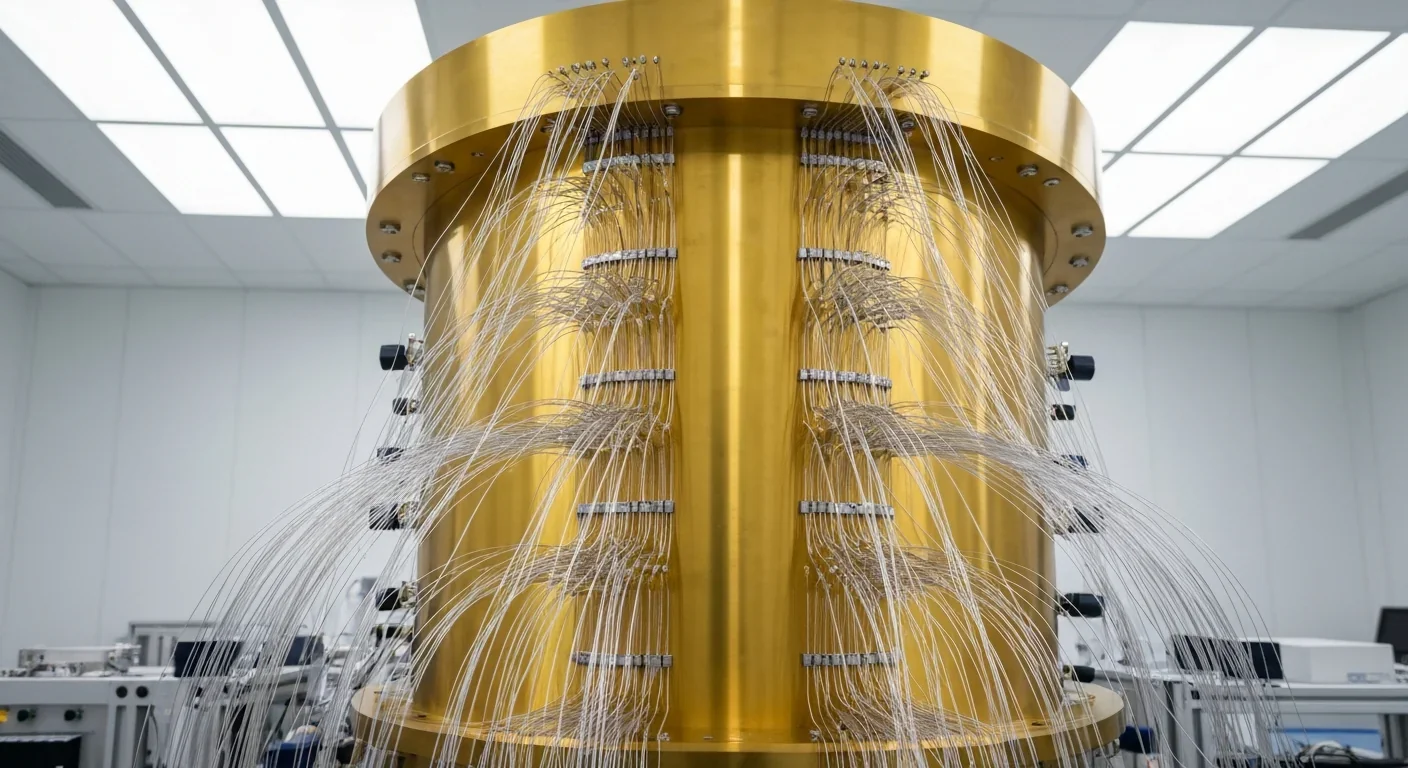

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.