Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: A groundbreaking 2025 study reveals the brain's map of the body remains surprisingly stable even years after amputation, overturning assumptions about phantom limb pain and forcing clinicians to rethink treatment approaches.

Imagine feeling an itch on your hand so vivid you reach to scratch it, only to remember the hand isn't there. For up to 80% of amputees, this isn't imagination but daily reality. Phantom limb syndrome reveals a startling truth about consciousness: your brain's model of your body can persist with astonishing stubbornness, generating sensations from limbs that no longer exist. A groundbreaking study published in Nature Neuroscience in August 2025 overturned decades of assumptions, showing that the brain's internal map of the body remains essentially unchanged even five years after amputation. This discovery forces us to rethink how we treat phantom pain and what it means to have a body at all.

Your brain maintains an exquisitely detailed map of your body in a ribbon of tissue called the somatosensory cortex, draped across the top of your head like a headband. This isn't just any map. It's a distorted representation where sensitive areas like your lips and fingertips claim vast neural real estate while your back gets barely a footnote. Scientists call this the cortical homunculus, and if you could see it, you'd encounter a grotesque figure with enormous hands, giant lips, and a tiny torso.

For decades, neuroscientists believed this map was plastic, constantly rewriting itself based on sensory input. Lose a hand, the theory went, and neighboring regions would colonize the abandoned territory. The face area would expand into the hand area, explaining why some amputees feel phantom sensations when their face is touched.

But Tamar Makin's team at the University of Cambridge discovered something unexpected. They followed three people scheduled for arm amputation, scanning their brains before surgery and repeatedly over the next five years. What they found challenged everything: the hand region didn't disappear or get invaded. It stayed right where it had always been, quiet but intact, like a house whose occupants have moved away but left the lights on.

"This is the most decisive direct evidence that the brain's in-built body map remains stable after the loss of a limb."

- Dr. Tamar Makin, University of Cambridge

The study represents a fundamental shift in how we understand cortical remapping and neuroplasticity after injury.

This stability explains a lot about phantom limb syndrome. Between 60% and 80% of amputees experience phantom sensations, ranging from the mundane (feeling the limb's position, temperature, or movement) to the bizarre (phantom jewelry, watches that weren't removed before surgery, or limbs that feel telescoped into the stump).

The persistence happens because your brain isn't primarily responding to sensory input from your body. Instead, it maintains an internal model, a prediction of what your body should be. When signals from a missing limb stop arriving, the brain doesn't erase the circuitry. It keeps generating expectations, creating the ghostly sensation of presence.

Think of it like phantom phone vibrations. Your brain predicts your phone will buzz based on past patterns, so sometimes you feel it vibrating when it isn't. Phantom limbs work similarly, except the prediction involves an entire limb with position, movement, and sometimes excruciating pain.

About 60% to 85% of people with phantom sensations also experience phantom pain, a separate and often debilitating condition. The pain can feel like crushing, burning, stabbing, or cramping. Some describe their phantom hand clenched in a permanent fist, fingernails digging into a palm that doesn't exist. This isn't just discomfort; it's pain intense enough to derail lives.

The discovery that cortical maps remain stable contradicts earlier influential research from the 1990s. V.S. Ramachandran, a neuroscientist famous for his work on phantom limbs, reported that when he touched the face of some arm amputees, they felt sensations in their phantom hand. This suggested the face representation had invaded the hand territory, a phenomenon called cortical reorganization.

Makin's longitudinal study found no evidence of this invasion. So what explains Ramachandran's observations? The answer likely involves pre-existing connections. Your somatosensory cortex isn't organized in completely separate boxes. Neighboring regions have overlapping connections. After amputation, these dormant pathways might become unmasked or enhanced, creating the illusion of remapping without actual territorial takeover.

The distinction matters tremendously for treatment. If the map doesn't reorganize, then therapies designed to reverse reorganization won't work. And indeed, treatments based on reversing cortical reorganization have shown limited success.

The implications for phantom pain treatment are profound and require rethinking established approaches.

To understand phantom limbs, you need to grasp how your brain creates your sense of embodiment in the first place. The somatosensory system works through a hierarchy. Receptors in your skin, muscles, and joints detect touch, temperature, pain, and position. These signals travel up your spinal cord to your thalamus, which acts like a relay station, then onwards to your primary somatosensory cortex.

But the information doesn't stop there. It flows to association areas that integrate touch with vision, hearing, and memory. Your brain combines bottom-up sensory data with top-down predictions to create a coherent experience of your body. This is called predictive processing, and it explains why phantom limbs feel so real. The prediction machinery runs even when the data stops flowing.

The somatotopic map in your cortex follows a specific organization. Starting from the top and moving down, you'd encounter representations of your toes, legs, trunk, arms, hands, face, and throat. The map is continuous and orderly, which is why damage to specific brain areas causes predictable sensory deficits.

What's remarkable is that this map seems to be largely innate rather than learned. Studies of people born without limbs sometimes show cortical representations of missing body parts they've never had. This suggests your brain comes equipped with a blueprint of the human body form, independent of actual experience.

Not all phantom sensations involve pain, but when pain occurs, it can be agonizing. The mechanisms behind phantom limb pain appear to involve multiple systems, not just the cortical map.

One factor is peripheral nerve activity. After amputation, nerve endings at the stump can form neuromas, tangled masses of nerve tissue that generate spontaneous electrical signals. Your brain interprets these chaotic signals as coming from the missing limb, creating pain sensations.

Another contributor involves changes in the spinal cord. When normal sensory input stops, inhibitory controls can weaken, allowing pain signals to amplify. This process, called central sensitization, means the nervous system becomes more reactive to stimulation, interpreting even mild signals as painful.

Research also points to emotional and psychological factors. Phantom pain often worsens with stress, anxiety, or depression. The relationship runs both ways: chronic pain increases psychological distress, which then amplifies pain perception, creating a vicious cycle.

Interestingly, some researchers propose that phantom pain might relate to a conflict between motor commands and sensory feedback. Your brain sends commands to move the phantom limb, but receives no confirmation that movement occurred. This sensory-motor mismatch might be interpreted as pain.

Given the complexity of phantom pain, it's not surprising that no single treatment works for everyone. The most commonly prescribed medications include antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and opioids, but their effectiveness varies widely. Many patients get only partial relief, and side effects can be significant.

Mirror therapy, developed by Ramachandran, involves using a mirror to create a visual illusion that the missing limb is present and moving normally. Patients place their intact limb in front of a mirror positioned so they can't see their stump. When they move the intact limb, they see it reflected where the missing limb should be. For some people, this visual feedback tricks the brain into resolving the sensory-motor mismatch, reducing pain.

A systematic review of mirror therapy protocols found evidence supporting its use, particularly for lower limb amputations. But results are inconsistent. Some patients experience dramatic relief; others notice no change. The optimal duration and frequency of sessions remain unclear.

Virtual reality takes mirror therapy further, creating immersive environments where patients can see and control their phantom limb. Early studies showed promising results, with some participants experiencing significant pain reduction. The technology allows for more sophisticated scenarios than a simple mirror, potentially engaging multiple brain systems simultaneously.

The sobering reality is that many amputees cycle through multiple treatments without finding adequate relief. The discovery that cortical maps remain stable suggests that approaches targeting cortical reorganization may be fundamentally misguided.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) applies electrical pulses to the skin, potentially interfering with pain signals. Acupuncture has been tried, though evidence remains mixed. Some patients report benefit from biofeedback, meditation, or cognitive behavioral therapy, approaches that target the psychological components of pain.

More invasive options include nerve blocks, surgical revision of the stump, or implanted spinal cord stimulators. A recent meta-analysis of neuromodulation techniques found that methods like repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and spinal cord stimulation showed promise, but more rigorous trials are needed.

If phantom pain is so difficult to treat, can it be prevented? This question has driven research into perioperative interventions, treatments administered before, during, and immediately after amputation surgery.

The logic is compelling: if phantom pain partly results from sensitization of pain pathways, then preventing that sensitization might stop pain from developing. Strategies include epidural anesthesia extending into the post-operative period, preemptive use of medications like gabapentin or ketamine, and aggressive management of pre-amputation pain.

Some studies suggest these approaches reduce phantom pain incidence and severity, but results aren't consistent. A systematic review of preventive approaches concluded that while some interventions show promise, the evidence base remains weak. Large, well-designed trials are scarce.

One intriguing approach involves using nerve transfer techniques during amputation surgery. Rather than simply cutting nerves and allowing them to retract, surgeons connect severed nerves to targets in the remaining limb. This targeted motor and sensory reinnervation might preserve more normal neural activity, reducing phantom sensations. Early results look encouraging, but the technique requires specialized expertise.

Beyond clinical implications, phantom limbs illuminate fundamental questions about consciousness and the self. Your experience of having a body isn't simply a passive reading of sensory data. It's an active construction, a simulation your brain runs continuously.

This becomes obvious when the simulation diverges from reality. Neuroscientists have induced phantom limbs in healthy volunteers using techniques like the rubber hand illusion. By synchronizing visual and tactile stimulation, they can make people feel ownership of a fake hand or even a telescoped limb.

"Your sense of embodiment relies on integrating multiple streams of information: vision, touch, proprioception, and motor commands. When these streams align, you feel ownership and agency. When they conflict, strange experiences emerge."

- Research on body ownership and agency

Phantom limbs represent an extreme case of this conflict. Your brain's body blueprint says the limb should be there. Motor systems continue issuing commands to move it. But sensory confirmation never arrives. The result is a profound disconnect between internal model and external reality.

Philosophers have long debated whether consciousness requires a body. Phantom limbs suggest the answer is nuanced. You can have conscious experiences of body parts that don't exist, yet these experiences still depend on having a brain structured by evolution to control a human body. Your conscious self is neither purely physical nor purely mental but emerges from their interaction.

Makin's discovery that cortical maps remain stable opens new research directions. If remapping isn't happening, what is? Scientists are investigating changes in other brain regions beyond the primary somatosensory cortex, including motor cortex, parietal association areas, and networks involved in body ownership.

Advanced neuroimaging techniques allow researchers to track these changes with unprecedented detail. Functional MRI reveals which brain areas activate during phantom experiences. Diffusion tensor imaging maps white matter connections, showing how different regions communicate. Combining these methods might identify biomarkers that predict who will develop severe phantom pain.

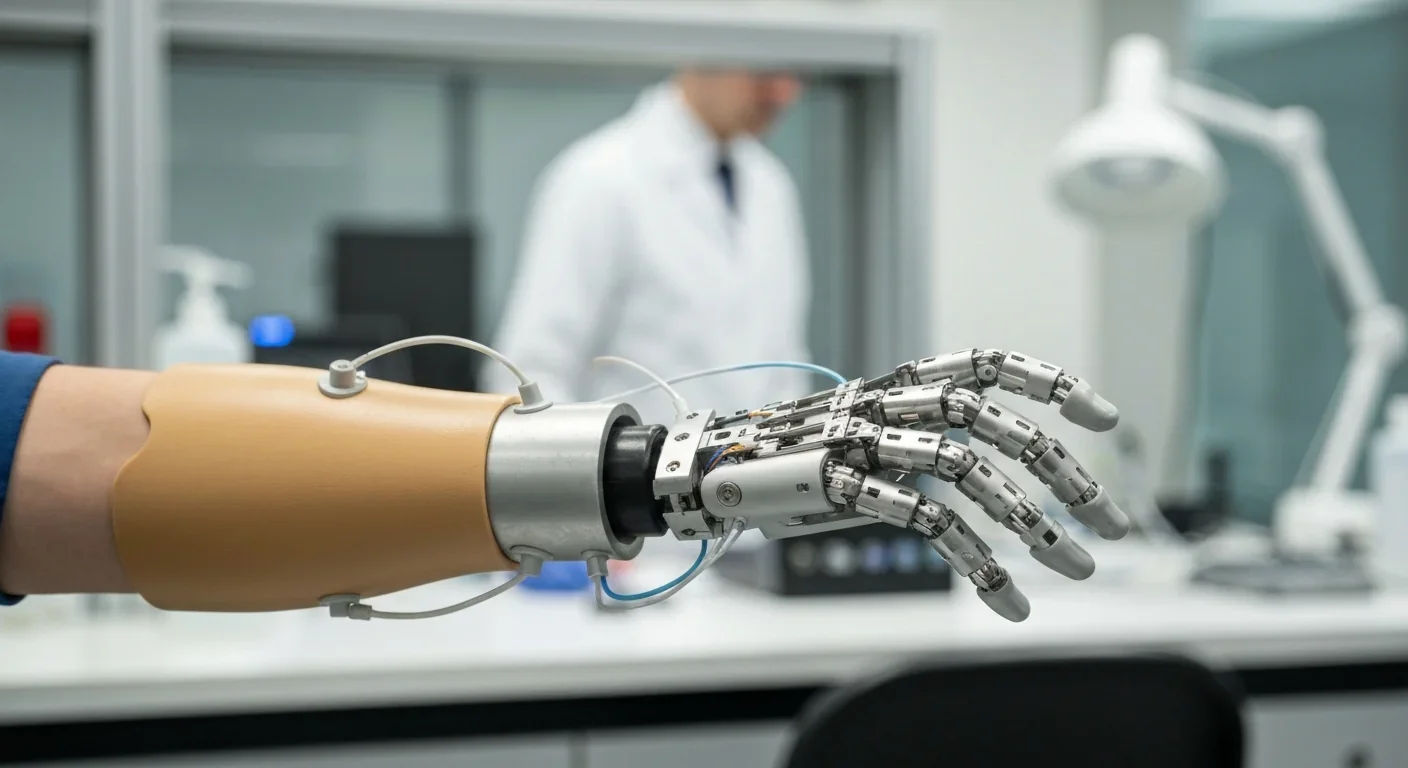

Prosthetics research is also benefiting from phantom limb insights. Modern prosthetic limbs can be surgically integrated with residual nerves and muscles, allowing users to control them through thought and receive sensory feedback. This bidirectional communication might satisfy the brain's expectations more fully, potentially reducing phantom sensations.

Some researchers are exploring neurofeedback approaches, training amputees to modulate activity in their hand cortex using real-time brain imaging. If people can learn to control this activity, they might gain some control over phantom experiences. Early pilot studies show feasibility, but whether this translates to meaningful clinical benefit remains unknown.

Pharmacological research continues to search for more effective medications with fewer side effects. Understanding the specific molecular pathways involved in phantom pain might enable more targeted interventions.

Virtual reality technology keeps improving, becoming more immersive and affordable. Clinical trials are testing VR protocols for acute post-operative phantom pain, potentially intervening before chronic pain establishes itself.

Behind all the neuroscience are millions of people navigating daily life with phantom limbs. Their experiences vary enormously. Some find phantom sensations reassuring, a connection to their lost limb. Others describe them as disturbing intrusions, constant reminders of loss.

Many amputees develop a pragmatic relationship with their phantom. They learn which movements or thoughts trigger sensations, which positions bring relief. Some can voluntarily move their phantom limb, using it to scratch phantom itches or relieve phantom cramps. For others, the phantom feels paralyzed in uncomfortable positions they can't change.

The emotional dimension deserves more attention than it often receives. Losing a limb involves grief, identity disruption, and often trauma. Phantom sensations can complicate this psychological process, making it harder to accept the loss and adjust to a changed body.

Support from others who've experienced amputation can be invaluable. Peer support groups, both in-person and online, provide spaces to share coping strategies and emotional validation. Hearing that phantom sensations are normal neurological phenomena rather than signs of mental illness can bring tremendous relief.

The revelation that cortical maps don't reorganize as previously thought demands a fundamental rethinking of treatment strategies. Interventions based on reversing reorganization, including some uses of mirror therapy, may need reframing or abandonment.

But the stable map finding also offers hope. If the hand region remains intact, it might be possible to tap into it more effectively with advanced prosthetics. Providing sensory input to the preserved hand cortex through nerve interfaces could create more intuitive prosthetic control and potentially reduce phantom pain by satisfying the brain's sensory expectations.

Researchers are also reconsidering the role of attention and cognitive factors. If the cortical map doesn't change much, then perhaps phantom pain relates more to how the brain interprets and reacts to signals from that stable map. Cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness meditation, and other attention-based interventions might prove more valuable than previously recognized.

The multifactorial nature of phantom pain suggests combination approaches may work best. Rather than seeking a single magic bullet treatment, clinicians might need to address peripheral nerve issues, spinal cord sensitization, cortical activity, and psychological factors simultaneously with personalized treatment plans.

Phantom limb syndrome sits at the intersection of neuroscience, medicine, psychology, and philosophy. Progress requires dialogue across these disciplines. The neurologist needs to understand the surgeon's techniques, the psychologist needs to know the neuroscience, and everyone needs to listen to patients' lived experiences.

Looking forward, several developments could transform care for people with phantom limbs. Genetic studies might reveal why some individuals develop severe phantom pain while others experience only mild sensations. This could enable risk stratification and preventive interventions for high-risk patients.

Brain-computer interfaces continue advancing rapidly, driven by both medical applications and consumer technology. As these systems become more sophisticated, the boundary between biological limb and prosthetic device may blur. Your brain might eventually control a robotic limb as naturally as it once controlled flesh and bone.

But technology alone won't solve everything. Better treatments require better understanding of subjective experience. Neuroscience has made enormous strides in mapping brain activity, but the hard problem remains: how physical processes in neurons create the felt quality of pain, the sensation of movement, the conviction that a missing limb is still present.

Phantom limbs offer a window into this mystery. They demonstrate that conscious experience can detach from physical reality while remaining grounded in neural activity. Studying this dissociation might reveal principles that apply to consciousness more broadly.

For now, phantom limbs remain exactly what they've always been: puzzling, fascinating, and for millions of people, an inescapable part of daily reality. Your brain's refusal to let go of its internal body model reflects both the power and the limitation of neural plasticity. The map in your head proves harder to redraw than anyone imagined, a testament to just how deeply your sense of self is encoded in the structure of your nervous system.

The ghost limbs that haunt so many amputees aren't supernatural. They're profoundly natural, revealing the brain's commitment to its own blueprint of the body. Understanding why that blueprint persists brings us closer to alleviating suffering and deeper into the mystery of what it means to inhabit a body at all.

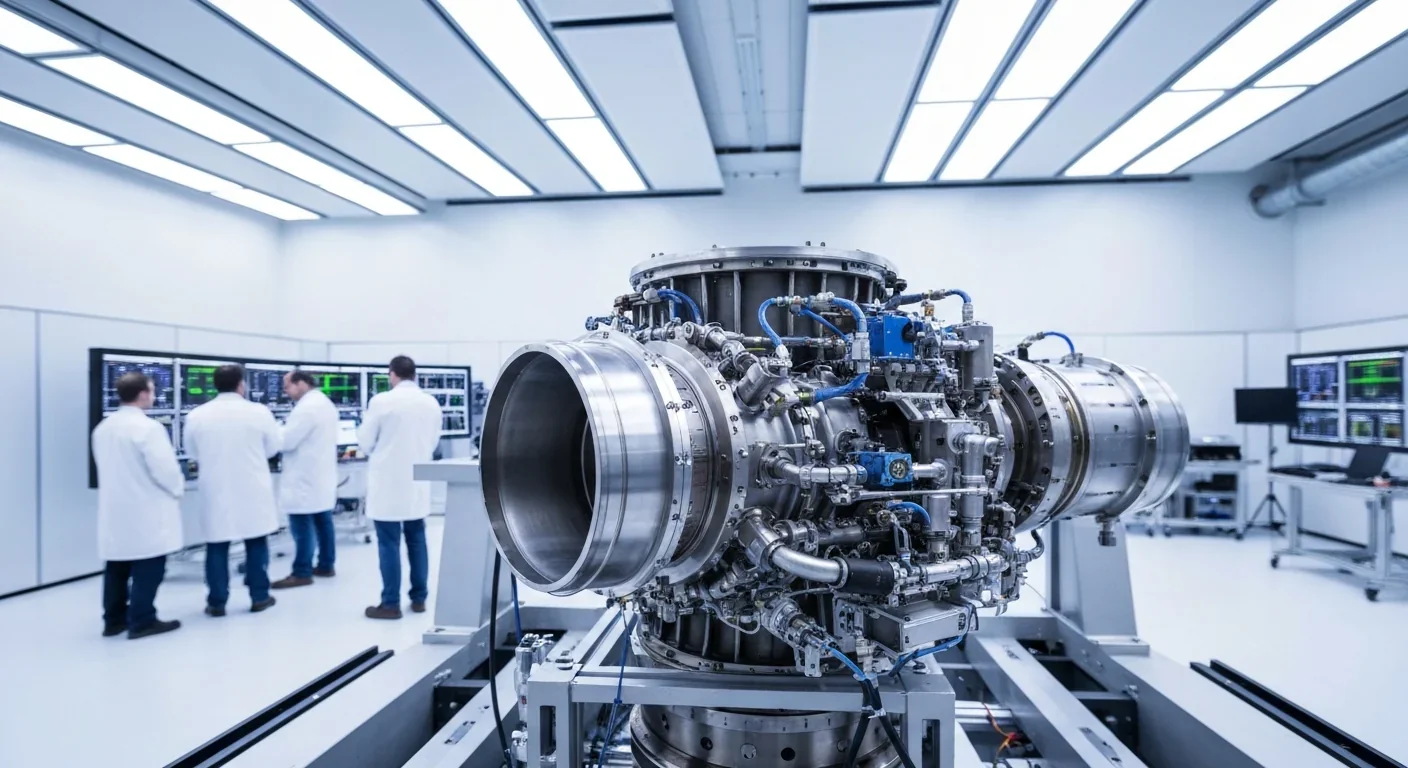

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

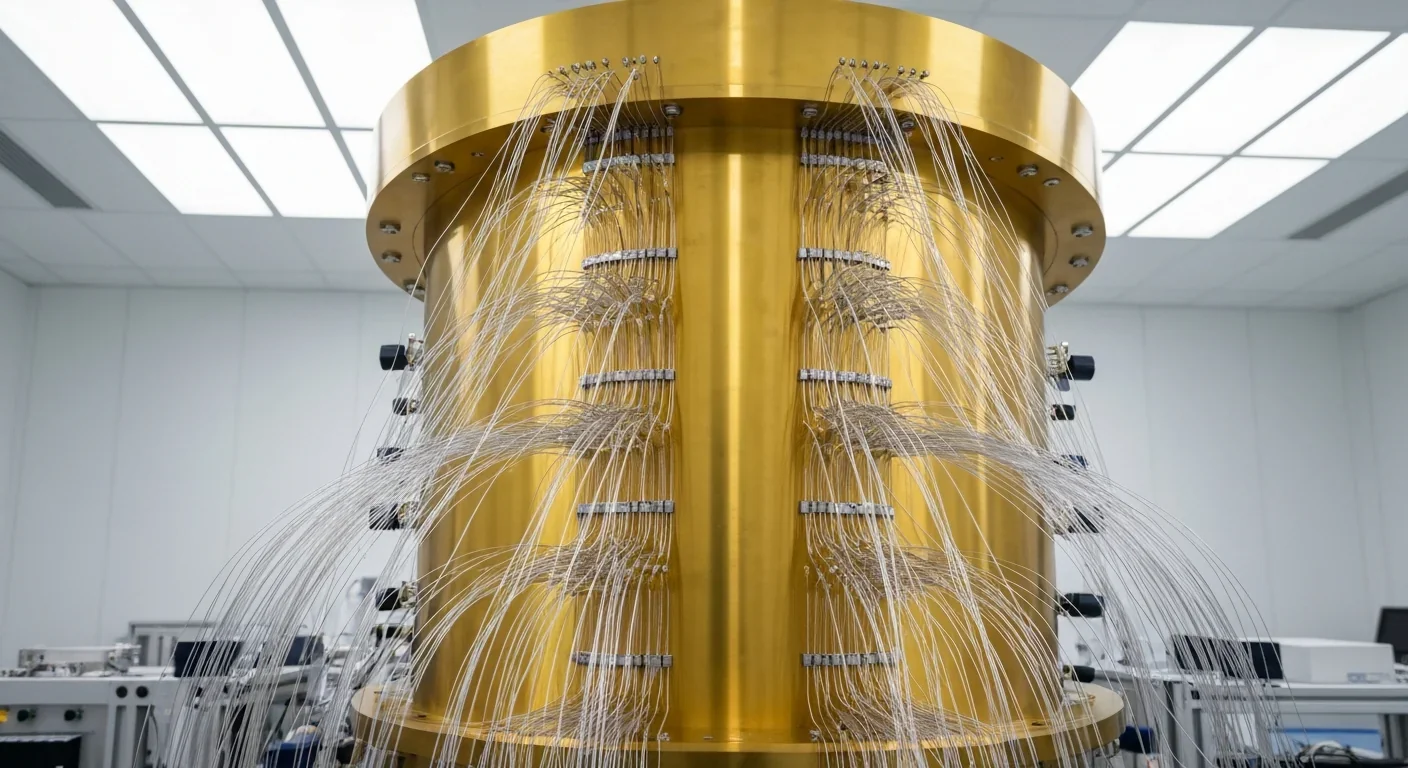

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.