The Ancient Protein Clock That Ticks Without DNA

TL;DR: Your gut contains 500 million neurons that form a sophisticated second brain, producing 90% of your body's serotonin and constantly communicating with your brain through the vagus nerve. This gut-brain connection directly influences mood, anxiety, and mental health through neurotransmitter production and microbiome interactions.

You've felt it before. That flutter of butterflies before a big presentation. The knot that forms when you're anxious. The sudden nausea that hits during stress. We call these "gut feelings," but they're far more than just metaphors. Deep inside your digestive tract lies a neural network so sophisticated, so extensive, that scientists call it your second brain.

The enteric nervous system (ENS) contains roughly 500 million neurons lining your gastrointestinal tract from esophagus to anus. That's five times more neurons than your spinal cord and about 0.5% of all the neurons in your brain. This isn't just a communication relay station sending messages to headquarters. Your gut can think for itself.

And increasingly, research shows it might be thinking about your emotional state more than you realize.

Most people assume the brain controls everything. Eat food, brain sends signals, gut digests. Simple hierarchy. But the ENS operates with stunning independence. Even when surgeons sever the vagus nerve, the main communication highway between gut and brain, the enteric system keeps functioning. Your gut literally doesn't need your brain to perform its core duties.

This autonomy comes from a complex two-layer structure. The myenteric plexus sits between muscle layers, coordinating the rhythmic contractions that move food through your system. The submucosal plexus regulates secretions and blood flow. Together, they form an integrated network that processes information locally, makes decisions, and executes commands without waiting for approval from above.

The ENS contains more than 30 different neurotransmitters, virtually identical to those found in your central nervous system. Acetylcholine, dopamine, serotonin, GABA - all the chemical messengers your brain uses to regulate mood, memory, and cognition are being manufactured and deployed in your gut. In fact, about 90-95% of your body's serotonin is produced right there in your intestines, along with roughly 50% of your dopamine.

Think about that for a moment. The "feel-good" neurotransmitter everyone associates with antidepressants? Your gut makes most of it.

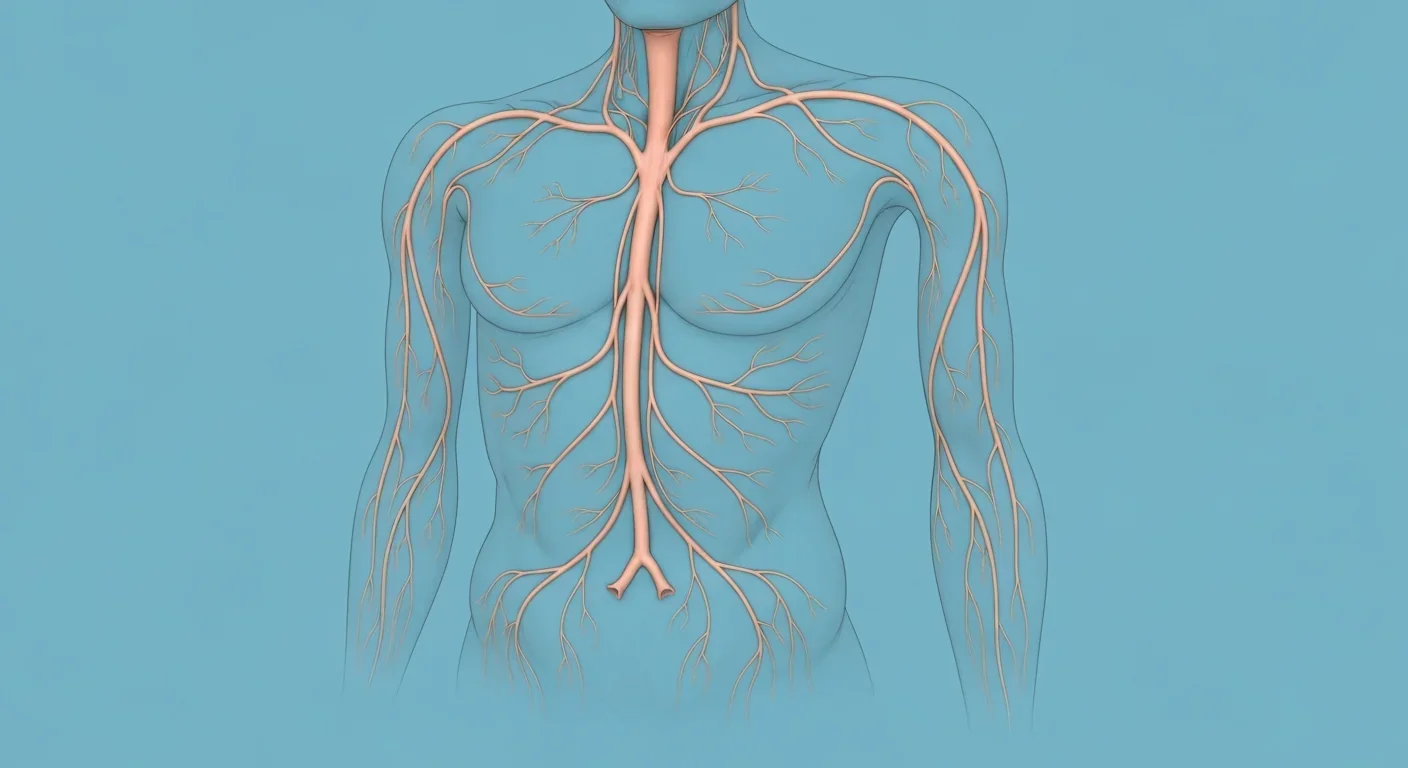

While the ENS can operate solo, it normally maintains constant dialogue with your brain through the vagus nerve, a massive information superhighway carrying signals in both directions. But here's the surprising part: approximately 90% of the vagus nerve fibers run from gut to brain, not the other way around.

Your gut is doing most of the talking.

Recent research has revealed just how direct this communication can be. When you eat, specialized cells called enterochromaffin cells release serotonin, which activates nearby nerve endings. These signals race up the vagus nerve to brain regions involved in mood regulation, anxiety response, and stress processing. The brain interprets this constant stream of gut data and adjusts your emotional state accordingly.

But the conversation flows both ways. When you're stressed, your brain sends signals down to your gut that can alter motility, increase inflammation, change the permeability of your intestinal lining, and even modify which bacteria thrive in your microbiome. Ever notice how anxiety makes your stomach upset? That's your brain talking to your gut, and your gut responding with its own neural cascade.

This bidirectional communication helps explain why gastrointestinal disorders and mental health conditions so often occur together. Studies show that 50-90% of people with irritable bowel syndrome also experience anxiety or depression. For decades, doctors assumed the psychological stress of having a chronic gut condition caused the mood problems. Now we know it's more complicated. The gut dysfunction itself may be driving changes in brain chemistry.

Your gut houses trillions of bacteria, collectively called the microbiome, and these microorganisms are active participants in the gut-brain conversation. Gut bacteria produce or help produce many neurotransmitters that influence your emotional state.

Different bacterial strains manufacture different compounds. Some species produce GABA, the brain's primary inhibitory neurotransmitter that helps calm anxiety. Others generate short-chain fatty acids that can cross the blood-brain barrier and directly influence neural function. Still others modulate the production of tryptophan, the precursor to serotonin, essentially controlling the raw materials your body uses to make mood-regulating chemicals.

When your microbiome is diverse and balanced, this chemical factory hums along smoothly. But when dysbiosis occurs - when harmful bacteria outnumber beneficial ones - the entire system can malfunction. Research has linked gut dysbiosis to depression, anxiety, autism spectrum disorders, and even neurodegenerative diseases.

One striking study found that toddlers with less diverse gut bacteria showed higher rates of anxiety and depression symptoms years later. Another revealed that babies' gut bacteria composition could predict their emotional regulation abilities as young children. The microbiome you develop early in life may set the stage for your mental health decades down the line.

"Animal experiments have suggested that a healthier variety of microbiota in your gut may help to relieve gastrointestinal, neurological, inflammatory and emotional stress symptoms."

- Cleveland Clinic Research Summary

Animal studies have been even more dramatic. Researchers can induce anxiety-like behaviors in mice simply by transplanting fecal matter from anxious animals into healthy ones. Transfer microbiota from calm mice into anxious ones, and their behavior improves. It sounds like science fiction, but fecal microbiota transplants are now being studied as potential treatments for depression in humans.

Understanding how this system works is one thing. Seeing what happens when it fails is another.

Take inflammatory bowel disease. Psychiatric disorders are remarkably common among IBD patients - depression rates run 2-3 times higher than the general population. For years, this was dismissed as an understandable reaction to living with a chronic illness. But mounting evidence suggests the gut inflammation itself is altering brain function through multiple pathways: inflammatory cytokines crossing the blood-brain barrier, disrupted neurotransmitter production, altered vagus nerve signaling, and microbiome shifts that reduce production of neuroprotective compounds.

Research on gut inflammation and depression shows these aren't separate conditions that happen to co-occur. They're connected manifestations of a disrupted gut-brain axis. Treat the gut inflammation effectively, and mood often improves. Address only the depression with antidepressants while ignoring gut health, and results tend to disappoint.

Autism spectrum disorder provides another revealing window into this relationship. Recent research has identified distinct microbiome patterns in children with autism, characterized by reduced diversity and altered ratios of specific bacterial families. Many autistic children also experience significant gastrointestinal problems. Studies exploring dietary interventions targeting the gut-brain axis have shown promising results in reducing both GI symptoms and some behavioral challenges, though the field is still early and results vary widely.

Even in people without diagnosed mental illness, subtle variations in gut function influence daily emotional experience. That's why stress reliably triggers digestive upset. Why certain foods seem to affect your mood. Why antibiotics that wipe out your microbiome sometimes come with unexpected changes in anxiety levels or mental clarity.

Your gut and your brain evolved together, each shaping the other's development. What you're experiencing as "mental health" isn't happening solely between your ears.

So what can you actually do with this information? The field of psychobiotics - probiotics specifically targeted at mental health - is still emerging, but some interventions show genuine promise.

Dietary approaches form the foundation. Your microbiome feeds on what you eat, so diet directly shapes bacterial composition. Fiber-rich whole foods, fermented products like yogurt and kimchi, and diverse plant-based nutrients support microbial diversity. Conversely, highly processed foods, excessive sugar, and artificial additives tend to favor inflammation and dysbiosis.

For people with irritable bowel syndrome, a short-term low-FODMAP diet implemented with professional guidance can reduce symptoms and improve quality of life. FODMAPs are fermentable carbohydrates that some bacteria feast on, producing gas and triggering GI distress. Temporarily limiting them can calm an overactive gut-brain axis and provide a reset.

Specific probiotic strains have shown mental health benefits in clinical trials. Bifidobacterium longum, for example, has demonstrated modest improvements in depression and stress symptoms. Lactobacillus rhamnosus has shown anti-anxiety effects in some studies. But results are strain-specific and dose-dependent. Not all probiotics affect mood, and taking random products off the shelf won't necessarily help.

The future of personalized psychobiotics will likely involve analyzing your specific microbiome composition and prescribing targeted bacterial strains to correct identified imbalances. We're not quite there yet, but the research pipeline is full.

Vagus nerve stimulation represents another therapeutic frontier. Techniques ranging from deep breathing exercises and cold exposure to electrical stimulation devices can enhance vagal tone - essentially strengthening the communication bandwidth between gut and brain. Some early research suggests this may help with both digestive disorders and depression, though large-scale validation is still needed.

Mind-body interventions work in both directions. Meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy, and stress management don't just calm your mind - they directly influence gut function. Studies on patients with functional GI disorders show that psychological interventions can reduce inflammation markers, normalize motility, and shift microbiome composition toward healthier patterns. The gut-brain axis responds to both ends of the conversation.

Exercise deserves special mention. Regular physical activity influences gut motility, increases microbial diversity, reduces inflammatory markers, enhances vagal tone, and triggers the release of mood-regulating neurotransmitters both centrally and in the gut. It's one of the most comprehensive gut-brain interventions available, and it's free.

One of the ENS's most intriguing features is something it shares with your brain: a diffusion barrier around its blood vessels. Just as your brain has a blood-brain barrier that carefully controls which substances can enter neural tissue, your gut has a similar protective system around its nerve clusters.

This barrier can break down. Chronic stress, poor diet, alcohol, certain medications, and gut dysbiosis can all increase "leaky gut" - a condition where the intestinal lining becomes more permeable. When this happens, bacterial components, incompletely digested food particles, and inflammatory molecules that should stay in the gut can enter the bloodstream and potentially reach the brain.

Some researchers believe this increased permeability plays a role in neuroinflammation linked to depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline. The theory remains somewhat controversial, but evidence continues mounting that gut barrier integrity matters for mental health, not just digestive function.

Strengthening this barrier involves many of the same strategies that support overall gut health: diverse fiber intake to feed beneficial bacteria that produce protective mucus, adequate intake of nutrients like zinc and vitamin A that support intestinal cell function, managing stress that can directly damage the gut lining, and avoiding chronic use of NSAIDs and other medications that compromise barrier integrity.

For decades, the enteric nervous system was viewed as a primitive, subordinate structure - a gut feeling in the most literal sense, but not worthy of serious neuroscience attention. That's changing rapidly.

Dr. Michael Gershon, the Columbia researcher who pioneered ENS research and coined the term "second brain," argues that understanding this system represents a paradigm shift in how we think about mental health. Depression and anxiety aren't just brain disorders. They're whole-body conditions in which the gut plays a starring role.

Imaging techniques are now allowing researchers to visualize the enteric nervous system in unprecedented detail, mapping neural circuits and identifying how different cell types interact. This work is revealing that the ENS is even more complex than previously thought, with specialized neurons for detecting nutrients, mechanical stretch, temperature, and chemical signals, all integrated into a processing network that rivals the sophistication of the spinal cord.

Studies on the microbiota-gut-brain axis in adolescent depression are showing that interventions during critical developmental windows might prevent or reduce mental health problems later in life. If gut health in childhood influences neural development and emotional regulation throughout adolescence, then pediatric nutrition and microbiome care become not just physical health issues but mental health imperatives.

"The enteric nervous system in humans consists of some 500 million neurons, approximately 0.5% of the number of neurons in the brain, five times as many as the one hundred million neurons in the human spinal cord."

- Furness, Journal of Gastroenterology, 2008

The implications extend beyond individual treatment. Research on the gut-brain axis in central nervous system diseases is exploring connections to Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's, multiple sclerosis, and other neurodegenerative conditions. Many of these diseases show gut dysfunction years before brain symptoms appear. The ENS may be an early warning system we haven't learned to read yet.

Traditional psychiatry has focused almost entirely on the brain. Prescribe an SSRI to boost serotonin in synapses. Use talk therapy to rewire maladaptive thought patterns. These approaches help millions of people, and they're not going away. But they're incomplete.

If 90% of your serotonin is in your gut, shouldn't treatment address both locations? If inflammation in your digestive tract is sending distress signals to your amygdala, shouldn't you calm the inflammation? If your microbiome is depleted of species that produce calming neurotransmitters, shouldn't you try to restore them?

The gut-brain axis framework doesn't replace existing mental health treatment. It expands it. Some people will respond better to probiotics than others. Some will find dietary changes transformative, while others see minimal benefit. Personalized medicine means identifying which interventions work for which patients based on their unique physiology, genetics, and microbiome composition.

We're entering an era where psychiatrists might order stool samples alongside psychological assessments. Where gastroenterologists routinely screen for depression. Where nutritionists work alongside therapists to address both gut and mental health simultaneously. The artificial boundary between digestive health and emotional wellbeing is dissolving because it was never really there.

You don't need to wait for personalized psychobiotic prescriptions to start caring for your gut-brain axis. The basics are accessible now.

Eat a diverse, fiber-rich diet with plenty of fermented foods. Your microbiome thrives on variety. Every different plant food you eat feeds different bacterial species, building a more resilient ecosystem.

Manage stress through whatever methods work for you - meditation, exercise, therapy, time in nature. Chronic stress is one of the most potent disruptors of the gut-brain axis, triggering inflammation, altering microbiome composition, and weakening your intestinal barrier.

If you're dealing with persistent digestive issues, don't dismiss the possibility that they're connected to your mood, anxiety, or cognitive function. Work with healthcare providers who understand the gut-brain connection and can address both ends of the axis.

Pay attention to how different foods affect not just your digestion but your mental state. Some people are highly sensitive to specific triggers. Identifying your personal patterns gives you actionable information.

Consider that your intuition might be more than metaphor. When you have a "gut feeling" about a situation, you're not experiencing some mystical phenomenon. You're experiencing your enteric nervous system processing information and communicating with your brain through neural pathways that operate below conscious awareness. Your second brain is offering its assessment. Maybe it's worth listening.

Research on the enteric nervous system and the gut-brain axis is exploding. Major questions remain unanswered. We still don't fully understand how gut bacteria communicate with neurons. We're still mapping which specific neural circuits connect which gut regions to which brain areas. We're still figuring out why some people's mental health responds dramatically to gut interventions while others see no benefit.

But the fundamental insight is settled: your gut is not just a digestive organ. It's a sophisticated neural network that independently processes information, manufactures neurotransmitters, communicates constantly with your brain, and influences your emotions, cognition, and behavior.

You're not one brain piloting a body. You're two nervous systems in constant conversation, each influencing the other, together creating what you experience as consciousness and emotion.

That changes everything about how we should think about mental health, nutrition, stress, and wellbeing. Your gut feelings aren't just feelings. They're your second brain speaking. And it's time we started listening more carefully to what it has to say.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

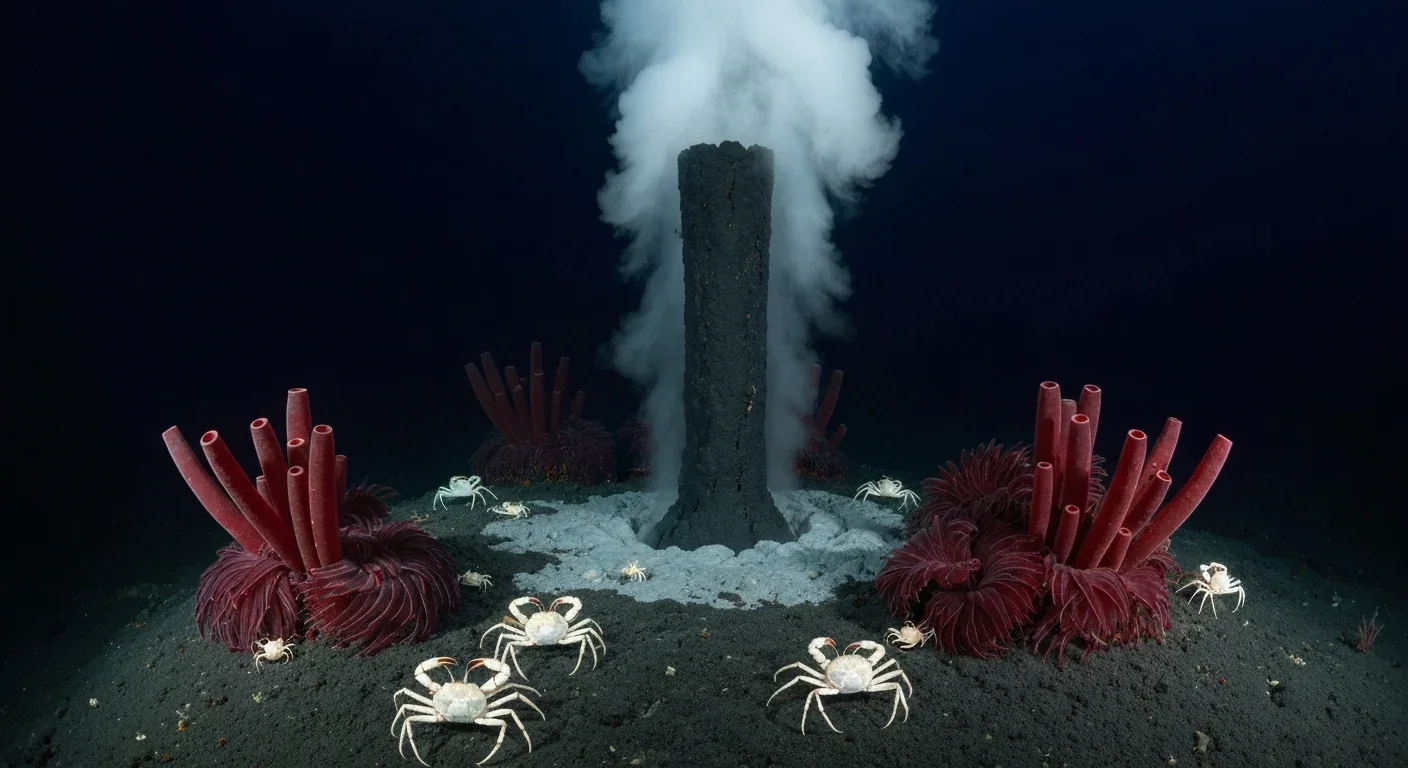

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

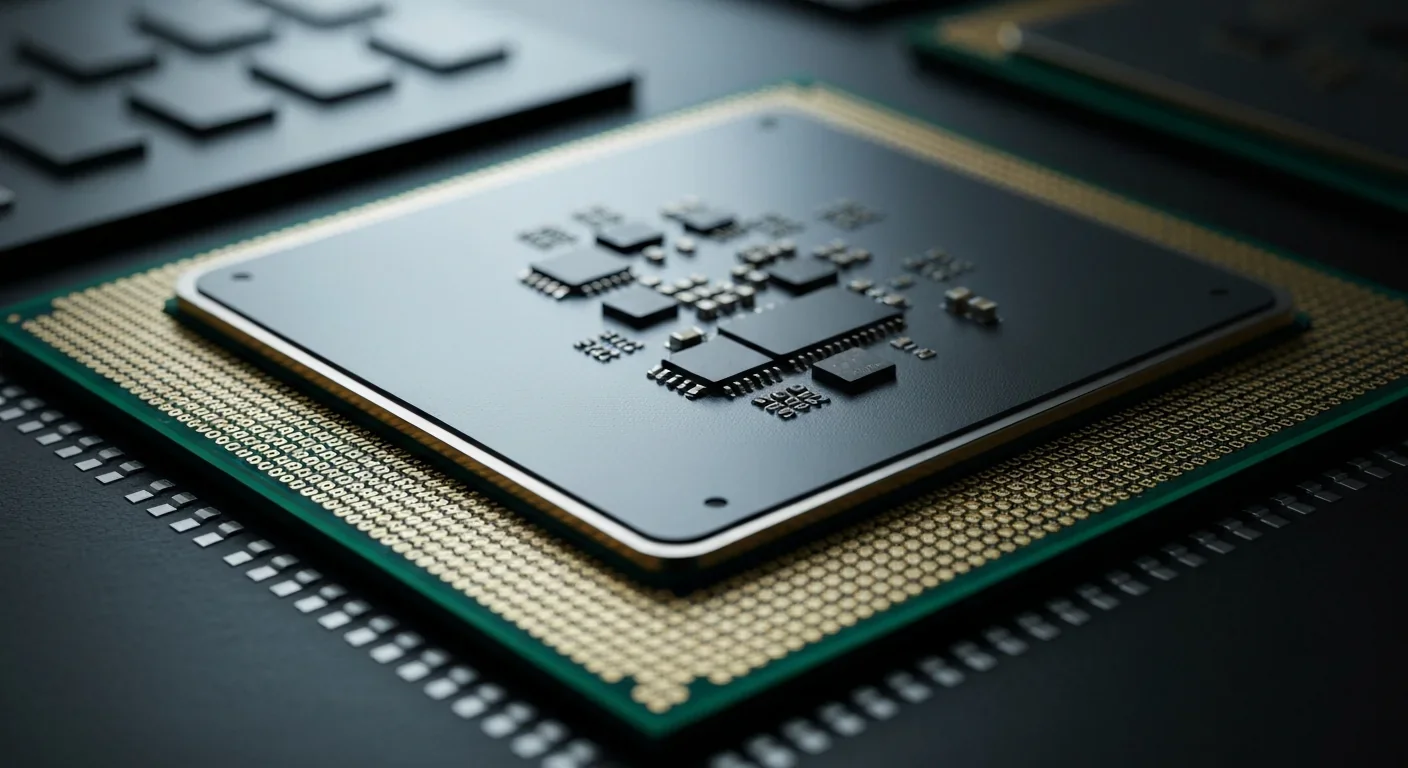

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.