Gut Bacteria Transform Bile Acids Into Powerful Hormones

TL;DR: Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

Your baby's immune system doesn't develop in isolation. Right now, microscopic organisms you've never heard of are sculpting the way your child's body will respond to threats for decades to come. Among these invisible architects, one group stands out as particularly powerful: segmented filamentous bacteria.

These aren't your typical gut microbes. Unlike the lactobacilli you recognize from yogurt labels or the bifidobacteria marketed in probiotic supplements, segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) operate behind the scenes with surgical precision, training immune cells at exactly the right developmental moment. Miss that window, and the consequences ripple through childhood and beyond.

SFB belong to an ancient lineage of bacteria that have coevolved with mammals for millions of years. Classified as Candidatus Arthromitus in the Clostridiaceae family, these organisms possess a feature that sets them apart from nearly every other gut microbe: they physically attach to the intestinal lining using specialized holdfast structures.

This intimate contact matters because it's not just about location. When SFB latch onto the epithelial cells of the ileum - the final section of the small intestine - they trigger a cascade of molecular signals that fundamentally reshape how the immune system matures. Think of it as a handshake that changes everything.

Scientists first discovered SFB in mice and rats during the 1960s, but it took another 50 years to confirm their presence in humans. Part of the delay stems from an unusual characteristic: these bacteria cannot be cultured using standard laboratory methods. They require the exact environment of the living ileum, making them extraordinarily difficult to study outside their natural habitat.

Timing is everything in immune development, and SFB seem to know this instinctively. Research tracking infant microbiomes has revealed that SFB abundance increases dramatically from 6 months of age, peaks around 12 months, and plateaus by 25 months post-weaning.

This timeline isn't coincidental. The first three years of life constitute what immunologists call a critical developmental window - a period characterized by high microbiota volatility before the gut ecosystem stabilizes into adult-like configurations. During this time, perturbations can predispose children to chronic inflammation and immune-related conditions later in life.

The 12-25 month window represents a developmental "sweet spot" when the infant gut is optimally responsive to microbial cues for immune training.

What drives SFB colonization during this specific window? The introduction of solid foods at weaning appears to be a key trigger. As infants transition from breast milk or formula to complementary foods, the dietary changes create conditions that favor SFB establishment. The bacteria respond to specific substrates present in solid foods, allowing them to proliferate and establish their characteristic attachment to the intestinal wall.

Vertical transmission from mother to infant also plays a crucial role. The origin of SFB in the gut is thought to occur through maternal fecal spores that may seed the infant during vaginal birth, similar to other gut microbes. This means the birthing process itself could influence whether and when a child acquires these important immune-training bacteria.

Once SFB establish themselves in the infant gut, they get to work educating immune cells. Their primary specialty? Training T-helper 17 (Th17) cells, a subset of white blood cells that defend mucosal surfaces throughout the body.

The evidence for SFB's role in this process is remarkably clear-cut. When researchers colonize germ-free mice - animals raised without any microbes - with fecal material that lacks SFB, no Th17 cells develop. Add SFB to the mix, and Th17 populations surge. This single-microbe rescue effect demonstrates just how essential these bacteria are for proper immune development.

"When fecal microbes, without SFB, from Jackson C57BL/6J mice, were introduced into germ-free mice, Th17 cells were not induced until SFB was added."

- Frontiers in Immunology Research Review

But how do SFB actually trigger Th17 cell differentiation? The mechanism involves an elegant molecular choreography. When SFB attach to epithelial cells, they stimulate the release of endocytic vesicles containing a bacterial cell wall-associated protein called P3340. These vesicles migrate to the lamina propria - the connective tissue beneath the epithelium - where they activate antigen-specific Th17 cells and induce production of interleukin-17 (IL-17), a key inflammatory signaling molecule.

Recent research has revealed even more granular details about this process. Studies on related bacteria like Alcaligenes faecalis show that gut microbes can enhance Th17 differentiation by manipulating the ubiquitination machinery inside T cells. Specifically, these bacteria inhibit the interaction between certain enzymes, leading to degradation of regulatory proteins and ultimately boosting transcription of genes essential for Th17 cell identity.

The sophistication of this system suggests it evolved over millennia as mammals and their microbial partners refined ways to optimize immune function.

While Th17 cells grab most of the attention, SFB influence immune development through multiple pathways. The changes extend far beyond a single cell type.

SFB colonization triggers production of antimicrobial peptides, including IL-22-induced compounds and RegIIIγ. These molecules help control the composition and location of other gut bacteria, preventing pathogenic species from gaining a foothold. In chicken studies, SFB-colonized birds showed significantly increased expression of β-defensin 14, an antimicrobial peptide, within one week of inoculation.

The bacteria also stimulate secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA), the antibody that coats mucosal surfaces and serves as the first line of defense against pathogens. Interestingly, SFB abundance correlates negatively with IgA levels in infant stool, suggesting a complex regulatory relationship where initial SFB colonization drives IgA production but eventual IgA elevation may then modulate SFB populations.

Perhaps most remarkably, SFB colonization increases intestinal expression of over 500 genes, including inflammatory cytokines, mucin genes, and numerous other factors involved in immune regulation. This profound transcriptomic impact demonstrates that SFB act as central modulators of gut mucosal function, orchestrating a coordinated response across multiple cellular systems.

The bacteria also influence the physical architecture of the immune system. SFB play a developmental role in the formation of Peyer's patches and isolated lymphoid follicles - specialized immune structures in the intestinal wall where immune cells congregate and coordinate responses. This links bacterial colonization directly to lymphoid organogenesis, showing that microbes literally help build the immune system's infrastructure.

What happens when infants don't acquire adequate SFB colonization? The consequences appear far-reaching.

Research on germ-free animals provides the most dramatic evidence. Mice raised without any microbes exhibit profound immune deficits: absence of lamina propria Th17 cells, impaired IgA secretion, underdeveloped lymphoid structures, and increased susceptibility to certain infections. Colonization with SFB reverses many of these problems, restoring normal Th17 populations and IgA responses.

Without proper SFB colonization, the immune system may fail to distinguish harmless antigens from genuine threats, potentially setting the stage for allergies and autoimmune conditions.

In animal models, SFB colonization provides protection against Citrobacter rodentium infection, a mouse pathogen similar to E. coli in humans. Similarly, chicken studies demonstrate that SFB-treated birds showed significant reductions in total Enterobacteriaceae and Salmonella levels compared to controls, with lower pathogen burdens persisting throughout the study period.

The human implications remain an active area of investigation, but early evidence suggests SFB absence or depletion during critical developmental windows may contribute to allergic diseases, inflammatory bowel disorders, and potentially even metabolic conditions. The connection makes mechanistic sense: without proper Th17 cell education, the immune system may fail to distinguish harmless antigens from genuine threats, setting the stage for inappropriate inflammatory responses.

There's also growing interest in the relationship between SFB and autoimmune disease risk. Th17 cells can be either protective or pathogenic depending on context. SFB-induced Th17 cells are homeostatic and non-pathogenic, whereas Th17 responses triggered by certain pathogens drive harmful inflammation. Early colonization by SFB may help "train" the immune system to generate protective rather than destructive Th17 responses.

If SFB colonization depends partly on dietary substrates, what we feed infants during the weaning period could directly influence their immune development. This possibility has captured the attention of nutritionists and immunologists alike.

Research suggests that dietary substrates can modulate SFB abundance, potentially influencing immune maturation. Genomic analyses of SFB have identified enzyme pathways for nutrient acquisition from diet, indicating these bacteria respond to specific food components.

A striking example comes from recent Columbia University research showing that mice fed a high-fat, high-sugar diet for four weeks experienced a sharp decline in SFB abundance. This reduction correlated with decreased Th17 cells and, notably, was associated with increased susceptibility to metabolic disease, diabetes, and weight gain.

"The drop in filamentous bacteria reduced the number of Th17 cells in the gut, which were found to be necessary for preventing metabolic disease, diabetes, and weight gain."

- Dr. Ivaylo Ivanov, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

The implications for infant nutrition are profound. During the 12-25 month window when SFB naturally peak, dietary choices that support these bacteria could optimize immune development. Conversely, early introduction of highly processed foods or excessive sugar might suppress SFB colonization at exactly the wrong time.

The relationship between formula feeding and SFB colonization remains less clear, though we know that formula-fed infants possess distinct gut communities characterized by different bacterial genera than breastfed babies. Whether these compositional differences affect SFB establishment specifically requires further study, but the overall pattern suggests feeding method influences the microbial ecosystem in ways that could impact immune-training bacteria.

Perhaps no factor poses a greater threat to healthy SFB colonization than early-life antibiotic exposure. These medications, while sometimes necessary, act as sledgehammers in the delicate ecosystem of the developing gut.

Studies demonstrate that antibiotic treatment leads to a substantial decrease in SFB densities in the intestine within just three days. More concerning, these disruptions occur during the very developmental window when SFB colonization should be ramping up.

The immune consequences extend beyond simple SFB depletion. Antibiotic treatment impairs naïve lymphocyte recruitment to Peyer's patches by affecting the function of high endothelial venules - the specialized blood vessels that allow immune cells to enter these structures. This suggests antibiotics disrupt not just the microbiome but also the immune system's ability to organize and coordinate responses.

The long-term health implications of early-life gut microbiome dysbiosis are increasingly well-documented. Alterations during the first 100 days appear particularly impactful for development of allergic diseases. Later disruptions have been linked to metabolic disorders, type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel diseases, and even atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Early-life antibiotic exposure should be minimized when safely possible, reserved for cases when bacterial infections truly threaten a child's health.

This doesn't mean antibiotics should never be used in infants. When bacterial infections threaten a child's health, these medications remain essential. But the mounting evidence suggests we need more judicious use, reserving antibiotics for truly necessary cases and exploring strategies to support microbiome recovery after treatment.

Understanding SFB's role in immune development opens fascinating therapeutic possibilities. If these bacteria are so crucial, could we deliberately introduce them to improve health outcomes?

Research in animal models suggests the answer may be yes. Studies in chickens have shown that oral inoculation of ileum-spores containing SFB after hatching increases early colonization, enhances immune maturation, and provides resistance to pathogens like Salmonella. The treated birds showed earlier SFB establishment and maintained protective benefits throughout the study period.

Translating this approach to human infants faces significant challenges. SFB's requirement for the ileal environment and inability to survive outside the host makes developing stable probiotic formulations difficult. However, recent advances in understanding SFB's molecular mechanisms - including the specific proteins and signaling pathways involved - could enable alternative strategies.

One possibility involves using other bacteria that trigger similar immune-educating effects. Research on Alcaligenes faecalis and its manipulation of the ubiquitination machinery suggests multiple microbial species might stimulate Th17 development through related pathways. Engineering or selecting bacteria with desired immune-training properties but better stability characteristics could circumvent SFB's cultivation challenges.

Another approach focuses on nutritional interventions. If we can identify the specific dietary substrates that promote SFB colonization, we might formulate infant foods or supplements that support these bacteria during critical developmental windows. This strategy could prove simpler and more practical than direct bacterial supplementation.

There's also interest in understanding why some infants naturally acquire robust SFB colonization while others don't. Geographic and population-level differences in SFB prevalence have been noted, suggesting environmental, dietary, or genetic factors influence colonization success. Identifying these factors could help predict which children might benefit most from interventions.

The science of SFB and infant immunity is still emerging, but several practical implications are already clear.

First, how infants are delivered matters. Vaginal birth exposes babies to maternal microbes, including potential SFB spores, that cesarean delivery bypasses. When C-sections are medically necessary, they save lives. But when they're elective, the microbiome impact deserves consideration in the decision-making process.

Second, early antibiotic exposure should be minimized when safely possible. This doesn't mean refusing necessary treatment, but it does mean having conversations with healthcare providers about whether antibiotics are truly required for a given illness and exploring alternatives when appropriate.

Third, what you feed your baby during weaning likely influences their immune development in ways we're only beginning to appreciate. Emphasizing whole foods over highly processed options and limiting added sugars during those critical 6-25 month windows could support healthy SFB colonization.

Fourth, the gut microbiome's importance means that disruptions - from antibiotics, dietary factors, or other causes - may have lasting effects. Supporting overall microbiome health through diet and lifestyle likely benefits the specific populations of immune-training bacteria like SFB.

Finally, this research highlights why the first three years of life deserve special attention from an immunological perspective. The gut ecosystem is in flux, the immune system is learning, and the patterns established during this window can persist for decades. Small interventions during this period may yield outsized benefits.

The story of SFB illustrates a profound truth about human biology: we are not individuals but ecosystems. Our health depends not just on our own cells but on trillions of microbial partners whose genes outnumber our own by a factor of 100 to 1.

This recognition transforms how we think about early childhood health. Supporting infant development means nurturing not just a single organism but an entire community of interdependent species. The bacteria in your baby's gut aren't passengers - they're active participants in building the immune system that will protect your child throughout their life.

As research continues, we're likely to discover even more about how specific microbial species contribute to health and disease. SFB represent just one example, albeit a particularly important one, of bacteria that serve essential developmental functions. Other species undoubtedly play similarly crucial roles in training different aspects of immune function or supporting other physiological systems.

This knowledge should inspire both humility and hope. Humility because it reveals how much we still don't understand about the microbial communities that shape human health. Hope because it suggests new avenues for preventing disease and optimizing development.

Your baby's immune system is being trained right now by invisible partners you've probably never considered. Understanding and supporting that process could be one of the most important things you do for their lifelong health.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

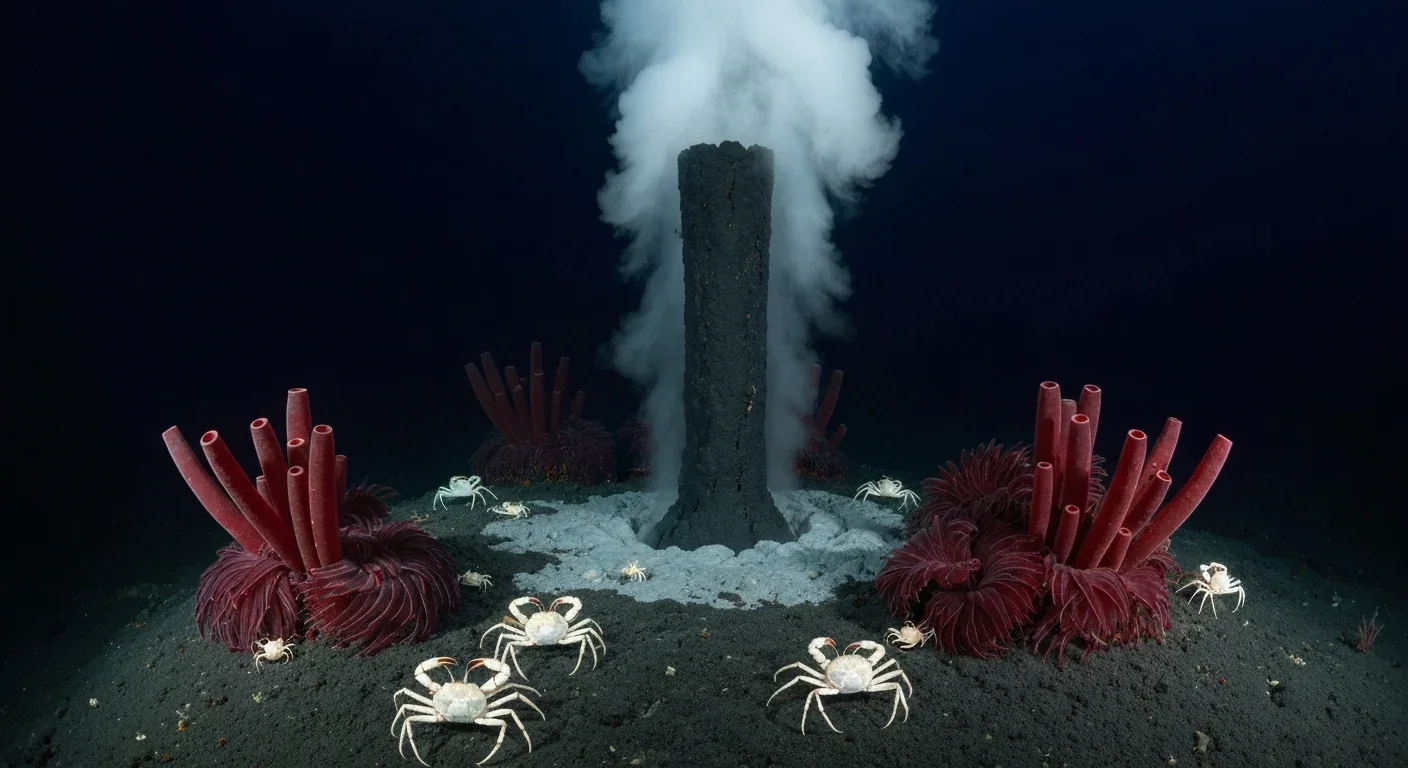

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.