Secret Bacteria That Train Your Baby's Immune System

TL;DR: Ancient viral DNA sequences making up 45% of your genome are reactivating as you age, triggering brain inflammation that may drive Alzheimer's disease - but repurposed antiviral drugs show early promise in blocking this process.

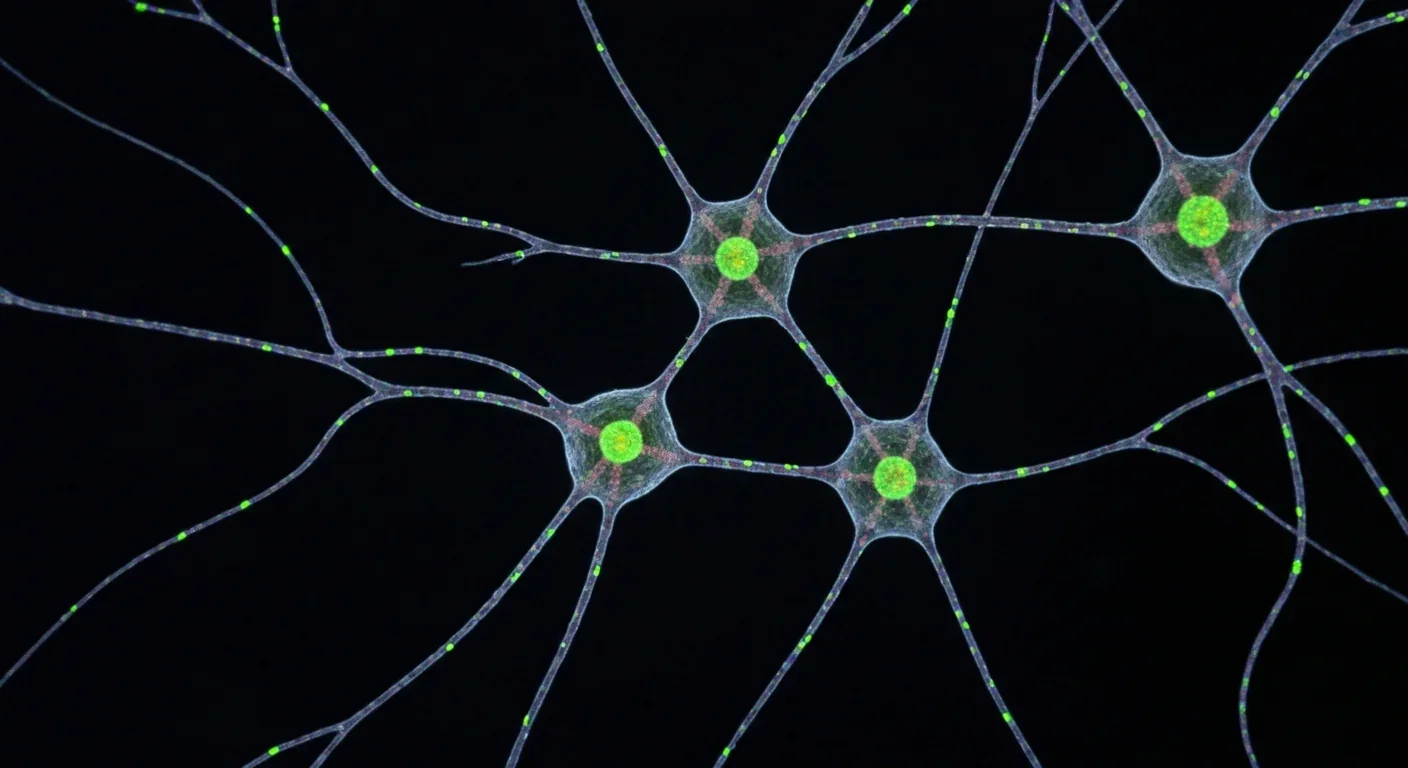

By 2030, neuroscientists predict that half of all Alzheimer's cases could be influenced by a hidden threat lurking inside your own cells - ancient viral-like DNA sequences called transposable elements, which make up nearly half of your genome. For decades, these "jumping genes" were dismissed as evolutionary junk, relics of long-extinct viruses that infected our ancestors millions of years ago. But cutting-edge research from 2025 and 2026 has revealed something unsettling: these sequences are waking up as you age, escaping the molecular locks that normally keep them silent, and triggering waves of inflammation that may be accelerating cognitive decline, neurodegeneration, and Alzheimer's disease. What's happening inside the nuclei of your brain cells could fundamentally change how we understand and treat brain aging.

The story begins not in a neuroscience lab, but in a cornfield. In the 1940s and '50s, geneticist Barbara McClintock made a startling discovery while studying pigmentation patterns in maize: some genes could move from one location in the chromosome to another, creating unexpected color patterns in corn kernels. She called them "controlling elements," but the scientific establishment largely ignored her work for decades. It wasn't until molecular biology caught up in the 1970s that researchers recognized the profound implications of her discovery, eventually awarding her the Nobel Prize in 1983. What McClintock had found were transposable elements (TEs) - fragments of DNA that can copy themselves and insert into new locations in the genome, disrupting genes and creating genetic diversity.

Today, we know that transposable elements comprise approximately 45% of the human genome, far more than the mere 2% that codes for proteins. About 17% of your DNA consists of LINE-1 (Long Interspersed Nuclear Element-1) retrotransposons alone. These aren't just passive passengers in your chromosomes; they're the evolutionary ghosts of ancient retroviruses that invaded our ancestors' genomes and became permanently embedded in our hereditary material. Most are now broken and inactive, silenced by millions of years of evolution. But roughly 80 to 100 LINE-1 copies remain capable of copying themselves and inserting back into the genome - a process called retrotransposition. In young, healthy cells, powerful epigenetic mechanisms keep these elements locked down, preventing them from wreaking havoc. As you age, those locks begin to fail.

Nearly half of your DNA is made up of ancient viral sequences that have been silent for millions of years - but they're waking up as you age.

Your cells employ a sophisticated security system to keep transposable elements quiet. The first line of defense is DNA methylation - chemical tags added to cytosine bases in DNA that physically block the transcription machinery from reading TE sequences. Think of it as sealing a dangerous book shut with molecular padlocks. The second layer involves histone modifications: the protein spools around which DNA is wrapped can be chemically altered to compress chromatin into tight, inaccessible bundles called heterochromatin, locking TEs away in the nuclear equivalent of a vault. In some tissues, a third guardian - the piRNA (PIWI-interacting RNA) pathway - provides an RNA-based surveillance system that recognizes and destroys TE transcripts before they can be translated into proteins.

Recent research has identified a key player in maintaining TE silencing. A 2025 study published in PubMed found that in the fruit fly Drosophila, a transcription factor called Traffic Jam binds to enhancer sequences within the Flamenco piRNA cluster, driving production of piRNAs that silence gypsy and other retrotransposons. When Traffic Jam is knocked down, Flamenco piRNA levels plummet, transposons escape repression, and female flies become sterile - a dramatic illustration of how finely tuned TE silencing must be for normal physiology.

But these defenses deteriorate with age. Global DNA methylation declines across tissues as we grow older, particularly at repetitive element loci where TEs reside. Heterochromatin gradually unravels, converting from tightly packed, silent regions into looser, transcriptionally permissive euchromatin. Studies in multiple organisms have documented age-related global DNA hypomethylation, especially pronounced at TE sequences. The molecular machinery that maintains these epigenetic marks - DNA methyltransferases, histone-modifying enzymes, chromatin remodelers - all show reduced activity or fidelity in aging cells. In the brain, this is compounded by another vulnerability: neurons are post-mitotic, meaning they don't divide, so they can't dilute accumulated damage by producing fresh daughter cells. Once chromatin structure degrades, once methylation marks are lost, the damage accumulates over decades.

The breakdown accelerates when additional stressors enter the picture. A groundbreaking 2025 paper in Alzheimer's & Dementia found that infection with human herpesvirus (HHV) triggers widespread transposable element dysregulation in aging brains, particularly in individuals with Alzheimer's disease. Chronic viral presence appears to actively remodel the TE landscape, creating a feedback loop in which infection drives TE reactivation, which in turn fuels inflammation that further compromises epigenetic silencing.

What happens when a LINE-1 element escapes its cage? The retrotransposon is transcribed into RNA, then translated into proteins - including an enzyme with reverse transcriptase activity, the same molecular machinery HIV uses to copy its RNA genome into DNA. This reverse transcriptase converts the LINE-1 RNA back into double-stranded DNA, which can then insert into a new genomic location. But this process is messy: the reverse-transcribed DNA often ends up floating in the cytoplasm rather than safely integrating into chromosomes. This is where the trouble truly begins.

Cells have evolved exquisitely sensitive detectors for foreign DNA in the cytoplasm, because that's a hallmark of viral infection. The primary sensor is an enzyme called cGAS (cyclic GMP-AMP synthase). When cGAS encounters double-stranded DNA in the cytoplasm - whether from a virus, a ruptured mitochondrion, or an escaped transposable element - it synthesizes a small molecule called cGAMP, which binds to and activates a protein called STING (Stimulator of Interferon Genes). Activated STING triggers a signaling cascade that culminates in the production of type I interferons and activation of the inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB.

"In senescent cells, cGAS gets activated by self-DNA present in the cytosol."

- Research published in Genes & Development

The cGAS-STING pathway is designed to detect viral invaders, but it can't distinguish between viral DNA and TE-derived DNA. When LINE-1 elements reactivate en masse during aging, the cell's innate immune system treats the situation as a viral infection, launching a sterile inflammatory response - inflammation without an external pathogen. In the brain, this triggers microglia (the brain's resident immune cells) and astrocytes (supportive glial cells) to release pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species. Chronic activation of this pathway creates a state of neuroinflammation that damages neurons, impairs synaptic function, and accelerates cognitive decline.

Research in aging mice has shown that this isn't theoretical. In cGAS knockout mice, accelerated aging and increased inflammation are linked to decreased DNA methylation on LINE-1 transposons, leading to their mobilization and activation of alternative DNA sensors like AIM2, which further fuel inflammation. Intriguingly, loss of cGAS paradoxically worsens inflammation because cGAS normally helps maintain chromatin stability; without it, TE derepression spirals out of control, engaging backup immune pathways in a destructive feedback loop.

There's an additional layer to this complexity: YAP/TAZ activity, which regulates nuclear envelope integrity through lamin B1 expression, declines with age. This decline promotes nuclear envelope blebbing and the formation of cytoplasmic chromatin foci (CCFs) - fragments of nuclear DNA that escape into the cytoplasm. These CCFs provide another source of cytoplasmic DNA that activates cGAS-STING, amplifying the inflammatory signal. Transposable element reactivation, nuclear envelope breakdown, and innate immune activation become a self-reinforcing cycle.

The most alarming evidence comes from human studies linking TE reactivation directly to Alzheimer's disease. A 2025 study analyzed brain tissue from two large biobanks - the Religious Orders Study/Memory and Aging Project (ROS/MAP) and the Mount Sinai Brain Bank (MSBB) - encompassing hundreds of Alzheimer's patients and controls. Using bulk RNA sequencing, researchers found widespread TE dysregulation in HHV-positive Alzheimer's brains, including an astrocyte-specific upregulation of LINE-1 subfamily TEs. In HHV-positive AD brains, LINE-1 expression increased up to fourfold compared to controls.

Critically, this upregulation correlated with increased amyloid-beta plaques and tau pathology - the hallmark lesions of Alzheimer's disease. LINE-1 up-regulation was particularly pronounced in astrocytes, where it modulated expression of NEAT1, a long noncoding RNA involved in neuroinflammation, via long-range chromatin interactions. Microglial activation paralleled TE upregulation, suggesting that TE-derived cytoplasmic DNA engages innate immune pathways culminating in microglial-driven inflammatory cytokine production.

Tau protein itself - the microtubule-associated protein that aggregates into neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's - may play a dual role in this process. Recent evidence suggests tau interacts with heterochromatin, helping to stabilize the repressive chromatin state. When tau misfolds and aggregates, it may lose this function, contributing to heterochromatin decondensation and TE derepression. Conversely, TE reactivation has been shown to increase tau phosphorylation and promote tau aggregation, creating another vicious cycle: tau pathology enables TE reactivation, which drives inflammation, which worsens tau pathology.

When transposable elements wake up, your brain's immune system can't tell the difference between your own DNA and a viral invasion - triggering inflammation that accelerates neurodegeneration.

The herpesvirus connection adds yet another dimension. Human herpesviruses - including HSV-1, the cause of cold sores - establish lifelong latent infections in the nervous system and periodically reactivate. The 2025 Alzheimer's & Dementia study found that HHV-positive brains showed extensive activation of LINE-1 elements, particularly in astrocytes and microglia. Viral infection appears to trigger TE derepression, possibly by interfering with host epigenetic machinery or by inducing chromatin remodeling as part of the host antiviral response. This intertwining of viral infection, TE reactivation, and innate immune activation creates a feedback loop that may underlie age-related neurodegeneration: viral reactivation drives TE activation, which triggers inflammation, which damages chromatin and enables further TE and viral reactivation.

Human observational studies reveal correlations, but animal models allow researchers to test causation. Studies in Drosophila have been particularly revealing. When researchers experimentally suppress TE activity in aging fruit flies - either by overexpressing piRNA pathway components or by genetic deletion of active TEs - they observe extended lifespan and reduced neurodegeneration. Conversely, flies with impaired TE silencing show accelerated brain aging and shortened lifespans. This suggests TE reactivation isn't merely a consequence of aging but an active driver of the aging process itself.

In mammals, similar patterns emerge. Mouse models with defective DNA repair or accelerated aging show increased LINE-1 expression and activity in the brain, accompanied by neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment. Mice lacking functional cGAS, rather than being protected from TE-driven inflammation, actually show worse outcomes because alternative DNA sensors compensate, and global chromatin instability worsens. The loss of cGAS leads to decreased DNA methylation on LINE-1 transposons, increased transposon mobilization, and activation of the AIM2 inflammasome, ultimately accelerating rather than ameliorating age-related inflammation.

Experimental models of tau pathology provide further support. Researchers used HEK293 cells engineered to express the P301S mutant form of tau - a mutation that causes familial frontotemporal dementia - and found that these cells showed elevated LINE-1 activation. When treated with antiviral drugs (discussed below), valacyclovir rescued tau-associated neuropathology and alleviated LINE-1 activation, with immunofluorescence showing reduced phosphorylated tau and qPCR confirming LINE-1 downregulation. Similar results were obtained in virus-infected human brain organoids - three-dimensional cultures of neural tissue grown from stem cells - which recapitulate many features of the developing and aging brain.

If TE reactivation drives neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, can we reverse it? The most promising approach so far involves repurposing drugs originally developed for other purposes. Reverse transcriptase inhibitors - drugs designed to block HIV replication - can also inhibit the reverse transcriptase activity of LINE-1 retrotransposons. Lamivudine (3TC), an HIV drug, has shown ability to reduce TE-associated inflammation in mouse models of aging. Similarly, valacyclovir and acyclovir - antiviral drugs commonly used to treat herpes infections - have shown remarkable effects in both cell culture and observational human studies.

The 2025 brain organoid study found that valacyclovir and acyclovir partially reversed LINE-1 dysregulation in HSV-1-infected human brain organoids. Single-cell RNA sequencing showed reduced LINE-1 expression after antiviral treatment. Even more striking, valacyclovir accelerated the breakdown of tau clumps, preventing their progression to neurofibrillary tangles, and reduced levels of LINE-1 ORF1p protein, the molecular machinery essential for retrotransposition.

"Anti-HHV drugs may suppress virus replication during reactivation events, reducing future risk of AD."

- Researcher quoted in News Medical study

Perhaps most compellingly, an AI-driven analysis of 80 million electronic health records found that individuals prescribed valacyclovir or acyclovir - typically for herpes simplex or shingles - showed statistically significant lower incidence of Alzheimer's disease, with the effect particularly pronounced in women over 75. This wasn't a randomized clinical trial, so it can't prove causation, but the association is striking and consistent with the mechanistic data. It suggests that anti-HHV drugs may suppress virus replication during reactivation events, reducing TE activation and thereby lowering future risk of Alzheimer's disease.

Epigenetic interventions represent another frontier. If age-related loss of DNA methylation and heterochromatin enables TE reactivation, can restoring these marks silence TEs again? Researchers are exploring small molecules that enhance DNA methyltransferase activity or promote heterochromatin formation. HDAC inhibitors, which modulate histone acetylation, and drugs targeting histone methyltransferases are being tested in preclinical models. The challenge is specificity: you want to silence TEs without inadvertently silencing essential genes or activating oncogenes. Targeting TE-specific transcription factor binding sites - analogous to the Traffic Jam enhancer interactions in Drosophila - might offer a more precise approach.

Another strategy targets the downstream inflammatory cascade. STING inhibitors are in clinical development for autoimmune diseases and could potentially dampen the neuroinflammation triggered by TE-derived cytoplasmic DNA. Senolytics - drugs that selectively kill senescent cells, which are major sources of TE reactivation and inflammatory signaling - have shown promise in mouse models of neurodegeneration, though their effects on human brain aging remain to be determined.

Despite rapid progress, critical questions remain. Does long-term antiviral therapy completely abrogate TE activation, or does it merely suppress viral reactivation without fully restoring TE silencing? The organoid data showed partial correction, but no longitudinal human data yet exists on sustained antiviral use for Alzheimer's prevention. Does chronic HHV infection directly induce DNA demethylation at LINE-1 loci, thereby facilitating transcriptional activation? The association is clear, but the mechanism linking viral infection to epigenetic remodeling at specific TE loci remains unknown.

The role of nuclear architecture is another frontier. Does age-associated decline in YAP/TAZ-driven nuclear envelope integrity increase cytoplasmic chromatin foci that facilitate transposon mobilization in neurons? If so, interventions that stabilize the nuclear envelope - perhaps through drugs that enhance lamin B1 expression or promote nuclear pore complex integrity - could prevent both CCF formation and TE escape into the cytoplasm.

Individual variability looms large. Why do some people show extensive TE reactivation and neuroinflammation while others maintain better TE silencing into old age? Genetic factors - such as APOE4 genotype, which is associated with both increased Alzheimer's risk and increased TE expression in AD brains - clearly play a role, but environmental factors (viral exposure, chronic stress, diet, exercise) likely modulate epigenetic maintenance as well. Understanding this heterogeneity could enable personalized risk stratification and targeted interventions.

Repurposing FDA-approved antiviral drugs could offer a rapid pathway to preventing Alzheimer's - observational studies already show lower dementia rates in people taking these medications.

Finally, the brain may be uniquely vulnerable to TE reactivation because neurons are post-mitotic and have limited DNA repair capacity compared to dividing cells. If true, therapies that enhance neuronal DNA repair pathways or boost autophagy (the cellular recycling process that clears damaged proteins and organelles, including cytoplasmic DNA) might synergize with TE-targeting drugs.

What Barbara McClintock discovered in corn kernels seven decades ago has led to a profound rethinking of human aging. Transposable elements are not inert junk DNA but dynamic genomic elements that, when derepressed, can drive a cascade of molecular events culminating in chronic inflammation and tissue degeneration. In the brain, where neurons cannot be replaced and inflammation is particularly toxic, TE reactivation may be a central mechanism linking genomic instability to cognitive decline.

This paradigm shift has immediate practical implications. If TE-driven inflammation is indeed a root cause of neurodegeneration, then we're not limited to treating downstream symptoms - amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, synaptic loss - but can address the genomic instability at the source. Reverse transcriptase inhibitors and antiviral drugs, already FDA-approved and widely used, offer a rapid pathway to intervention. Observational evidence suggests benefit; prospective clinical trials are the logical next step.

The broader lesson is that aging may be fundamentally a failure of genome maintenance. Epigenetic drift, transposable element reactivation, accumulation of cytoplasmic DNA, activation of innate immune pathways - these are all manifestations of the genome losing its organizational integrity over time. TE-driven inflammation may serve as a common denominator linking diverse aging hallmarks: genomic instability, chronic inflammation, and tissue dysfunction all converge on the reactivation of ancient viral relics embedded in our chromosomes.

As we move into the third decade of the 21st century, the field is poised at a remarkable juncture. The molecular mechanisms are becoming clear, animal models demonstrate causation, human correlative data are strong, and repurposed drugs show early promise. Within the next few years, randomized controlled trials of reverse transcriptase inhibitors for Alzheimer's prevention could begin enrollment, moving from electronic health record associations to definitive causal tests.

Perhaps most intriguingly, this research blurs the line between infectious disease and aging. Herpesvirus infection, which most humans acquire, may not just cause cold sores or shingles but could contribute to Alzheimer's disease decades later by triggering transposable element reactivation. If validated, this would represent a new category of pathogen-associated chronic disease - one that operates not through direct viral damage but by awakening the genomic ghosts we all carry.

The jumping genes are waking up. The question now is whether we can put them back to sleep before they accelerate the decline of the aging brain. The answer may determine the cognitive fate of hundreds of millions of people worldwide as the global population ages. Understanding TE reactivation could fundamentally change how we approach age-related neurodegeneration - from treating symptoms to addressing a root genomic cause, potentially adding years of cognitive health to human lifespan. The ancient invaders in our genome, once dismissed as junk, have become the frontier of aging research and a beacon of hope for preventing the diseases that steal our memories and minds.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

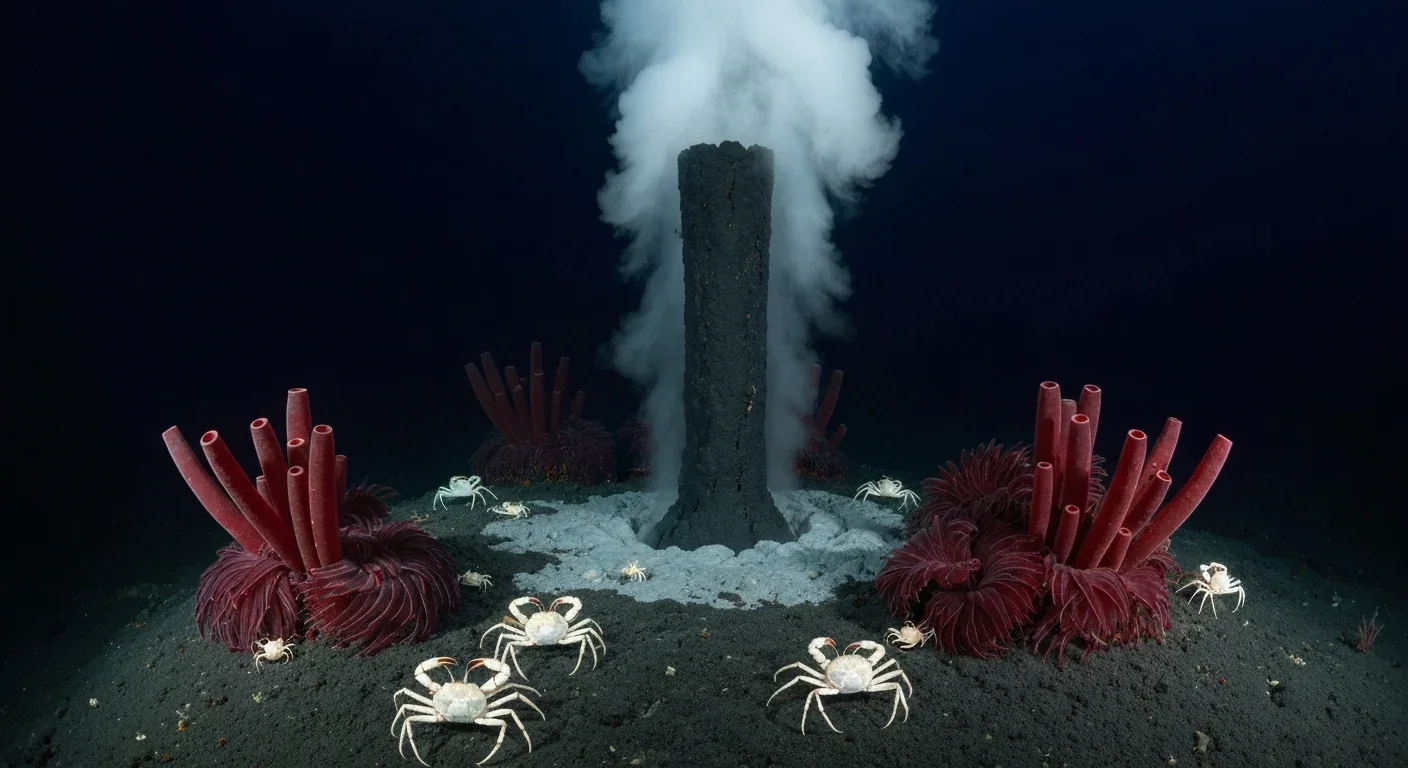

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.