Ribosomal Stress: When Broken Protein Factories Cause Cancer

TL;DR: Banned pesticides like DDT persist in food chains for decades, concentrating in fatty fish and dairy products, then accumulating in human tissues where they disrupt hormones and increase health risks.

Your grandmother's diet included DDT. So did your mother's. And despite these chemicals being banned before you were born, there's a decent chance yours does too. The pesticides we outlawed generations ago haven't disappeared - they've just moved up the food chain, concentrating in the fish you ate last Tuesday and the milk your kids drank this morning.

This isn't a historical curiosity. It's an ongoing chemical experiment with billions of unwitting participants.

In the 1940s through the 1970s, organochlorine pesticides like DDT, chlordane, and dieldrin were agricultural superstars. They killed pests effectively and cheaply, revolutionizing farming and helping eradicate malaria in many regions. The United States used DDT extensively from the 1940s until its ban in 1972, with global production of organochlorine pesticides exceeding 2 million tons before restrictions took effect.

Then came the bad news: these chemicals persist in the environment for decades, resist breaking down, and accumulate in living tissue. By the time most industrialized nations banned them in the 1970s, we'd already distributed them across virtually every ecosystem on Earth.

Here's the unsettling part: DDT is still detected in human blood samples today, more than 50 years after the U.S. ban. These organochlorines earned the designation "persistent organic pollutants" (POPs) because they can remain active in soil and sediment for 30 years or more. Some metabolites of DDT have half-lives measured in decades, meaning they'll be detectable in the environment well into the 22nd century.

The chemicals didn't vanish when we stopped spraying them. They just started a slow migration through every food chain on the planet.

The mechanism behind this persistent contamination is elegantly simple and deeply disturbing. Organochlorines are fat-soluble, which means they dissolve in oils and fats rather than water. When organisms absorb these chemicals - whether from contaminated soil, water, or food - the compounds lodge in fatty tissues instead of being excreted.

This creates two escalating problems: bioaccumulation and biomagnification.

Bioaccumulation occurs when an individual organism absorbs a toxin faster than it can eliminate it. Over its lifetime, that organism builds up higher and higher concentrations in its tissues. An algae cell might absorb a tiny amount of DDT. A small fish eating thousands of algae cells accumulates all their DDT. Then biomagnification kicks in.

Biomagnification is the process by which these concentrations increase at each level of the food chain. The EPA reports that organochlorine concentrations can increase by 10 to 100-fold at each trophic level. A dramatic example comes from a 1997 Arctic study: PCBs (another organochlorine) were found at 10 times higher levels in caribou tissue compared to the lichen they ate, and 60 times higher in wolves compared to lichen.

Humans sit near or at the top of many food chains. That places us squarely in the crosshairs of biomagnification.

When you eat a large predatory fish like tuna or swordfish, you're not just eating that fish - you're eating a concentrated accumulation of every pesticide molecule that passed through the entire ecosystem beneath it. The small fish ate contaminated plankton. Larger fish ate dozens of small fish. The tuna ate hundreds of mid-sized fish. And you ate the tuna, inheriting the chemical legacy of thousands of organisms.

One of the most disturbing aspects of organochlorine persistence is how far these chemicals travel. Arctic populations show high organochlorine levels despite no local pesticide use whatsoever. How did pesticides sprayed on cotton fields in Alabama end up in the fatty tissue of Arctic seals and the people who eat them?

POPs travel through atmospheric transport, ocean currents, and migratory species. When pesticides volatilize in warm climates, they can be carried by global wind patterns to cold regions where they condense and deposit. This "grasshopper effect" means chemicals used primarily in tropical and temperate zones accumulate in polar regions, far from their original application sites.

"POPs can be transported by wind and water, and can accumulate on particles that resuspend into the environment."

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

The result is a global distribution system that recognizes no borders. Coastal waters off the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico show persistent organochlorine contamination in marine life decades after use declined. The Great Lakes continue to harbor significant concentrations of PCBs and other organochlorines in sediments, creating ongoing exposure pathways through the fish populations that millions of people eat regularly.

Even more troubling, these chemicals don't stay put in sediment or soil. Seasonal changes, storms, and dredging activities can remobilize contaminants, releasing them back into the water column where they re-enter food chains. Legacy contamination sites act as persistent sources, continuously seeding new generations of organisms with old chemicals.

The health implications of chronic organochlorine exposure span nearly every system in the human body. These compounds function as endocrine disruptors, interfering with hormone signaling pathways that regulate development, reproduction, metabolism, and immune function.

DDT and its metabolites have been linked to increased risk of breast cancer, particularly in women exposed during critical developmental windows. The chemical's ability to mimic estrogen creates ongoing disruption in hormone-sensitive tissues. Research has also established connections to liver cancer, reproductive dysfunction, and developmental abnormalities in children exposed in utero or through breastfeeding.

Organochlorines are neurotoxic, affecting brain development and function. Children exposed to elevated levels show measurable deficits in cognitive performance and increased rates of attention disorders. The developing fetus and young children are particularly vulnerable because their rapidly growing tissues concentrate these fat-soluble compounds, and their immature detoxification systems can't efficiently eliminate them.

Perhaps most disturbing is that breast milk contains measurable levels of organochlorines and other POPs globally. This creates an impossible dilemma for parents: breast milk remains the optimal food for infants, yet it serves as a primary route of exposure to persistent toxins. Mothers who consumed contaminated fish and dairy products throughout their lives concentrate those chemicals in breast tissue, then transfer them to their nursing infants in highly bioavailable form.

Over 90% of human exposure to organochlorines comes through diet, not through drinking water or breathing air.

The CDC's National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) has been tracking organochlorine levels in the U.S. population since the 1970s. While levels have generally declined since the bans took effect, they haven't approached zero. Certain populations show persistently elevated levels, particularly those who consume large quantities of fatty fish, live near contaminated sites, or work in industries handling legacy chemicals.

Military personnel face unique exposure risks. A recent study found that endocrine-disrupting chemical mixture exposure correlated with increased risk of papillary thyroid cancer in U.S. service members, highlighting how occupational exposures can concentrate risk in specific populations.

When the U.S. banned DDT in 1972, it seemed like a decisive victory for environmental health. Over the following decades, most industrialized nations implemented similar bans, and international agreements like the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants created a global framework to eliminate the worst offenders.

Yet regulatory gaps persist. The EPA still maintains tolerance levels for organochlorine residues in food, acknowledging that complete elimination isn't feasible. These tolerance levels define "acceptable" contamination - a regulatory compromise between ideal safety and practical reality.

The concept of pesticide action levels creates a regulatory framework that sounds protective but has significant limitations. These levels are set based on toxicological studies, but they often fail to account for cumulative exposure from multiple sources, the cocktail effect of multiple chemicals acting together, or the heightened vulnerability of certain populations.

Monitoring presents another challenge. The EPA and other agencies track contaminant levels in food, water, and human tissues, but monitoring alone doesn't eliminate exposure. It simply documents the ongoing problem. Since 1987, the EPA has reduced dioxin and furan releases by more than 85% from known industrial sources - impressive progress, but it doesn't address the massive reservoir of legacy contamination already distributed throughout ecosystems.

International cooperation has achieved genuine progress. The Stockholm Convention, which entered into force in 2004, has united 185 countries in the effort to eliminate POPs. The treaty has successfully restricted or banned dozens of chemicals and established mechanisms for countries to support each other in meeting reduction targets. Yet enforcement remains uneven, and some nations continue to use DDT for malaria control under WHO exemptions, creating ongoing sources of environmental contamination.

The global nature of contamination means that purely national efforts fall short. Chemicals deposited in one country can volatilize and travel to another. Fish migrate across international waters, carrying their chemical burdens with them. Effective management requires coordinated global action, but geopolitical realities often impede the cooperation necessary to address a problem that recognizes no borders.

Not everyone carries the same organochlorine burden or faces equal risk from exposure. Several factors concentrate risk in specific populations.

Geography matters enormously. People living near former manufacturing sites, agricultural areas with heavy historical pesticide use, or contaminated waterways face elevated exposure. Indigenous communities in the Arctic - despite being thousands of miles from where these pesticides were applied - show some of the highest organochlorine levels in the world due to their traditional diets rich in fatty marine mammals that sit atop long food chains.

Diet is perhaps the single greatest determinant of exposure. The primary route of organochlorine exposure for most people is through food, particularly animal products high in fat. Fatty fish from contaminated waters, dairy products, and meat concentrate these chemicals far more than plant foods. A Consumer Reports investigation found measurable pesticide residues across the food supply, with the highest levels in animal products.

Age and developmental stage profoundly affect vulnerability. Fetuses, infants, and children face disproportionate risks because their developing systems are more sensitive to endocrine disruption, and their body burden relative to size is higher. A nursing infant can receive significant organochlorine exposure through breast milk, particularly if the mother consumed contaminated foods throughout her life.

Occupational exposure remains significant for workers in certain industries. Agricultural workers on lands with legacy contamination, cleanup crews at Superfund sites, and military personnel at bases with historical pesticide use face elevated risks. These populations often lack adequate protective equipment or information about the specific chemicals they may encounter.

Socioeconomic factors compound these risks. Lower-income communities are more likely to be located near contaminated sites, have less access to diverse food sources that could reduce reliance on contaminated fish or local game, and face barriers to healthcare that could identify and address exposure-related health problems.

The persistence of organochlorines means complete avoidance is impossible, but practical steps can meaningfully reduce exposure.

Make informed food choices. The single most effective strategy is adjusting your diet. Fatty fish from contaminated waters represent the highest dietary exposure risk. Choose smaller fish species that live shorter lives and occupy lower trophic levels - sardines, anchovies, and wild salmon from clean waters accumulate far fewer contaminants than tuna, swordfish, and king mackerel. Trim visible fat from meat and poultry, and select lower-fat dairy options when possible, as organochlorines concentrate in fat.

Diversify your seafood sources. If you regularly consume fish from the same lake, river, or coastal area, you're concentrating your exposure from that specific contamination profile. Varying your sources distributes risk across different environments with different contamination levels. Check local fish advisories before eating recreationally caught fish.

"Organochlorine concentrations increase by 10 to 100-fold at each trophic level."

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Choose organic when it matters most. While organic certification doesn't guarantee complete freedom from organochlorines (since these chemicals persist in soil and can drift from neighboring conventional fields), organic farming practices reduce overall pesticide burden. Consumer Reports identifies specific conventional produce items with consistently higher pesticide residues, making these strategic targets for buying organic.

Support cleanup efforts. Many communities have legacy contamination sites that continue to release organochlorines into local food chains. Supporting remediation projects, whether through advocacy or direct participation, reduces the ongoing source of exposure. Soil remediation techniques continue to improve, offering hope for eventually reducing the reservoir of contamination in hot spots.

Pregnant and nursing women need special attention. If you're pregnant, planning pregnancy, or nursing, minimizing organochlorine exposure protects your child during critical developmental windows. This doesn't mean avoiding breastfeeding - the benefits far outweigh the risks - but it does mean being strategic about your diet during these periods.

Demand better monitoring and reporting. Much of our food supply isn't routinely tested for organochlorine residues. Stronger monitoring requirements would provide consumers with better information and create incentives for producers to source from less contaminated areas. Contact your representatives to support expanded food testing programs.

Think generationally. The organochlorine problem spans decades. Decisions we make today about chemical use, environmental cleanup, and food system management will affect exposure levels for generations. Supporting policies that accelerate cleanup, prevent new persistent pollutants from entering use, and strengthen international cooperation on POPs management addresses the root causes rather than just managing symptoms.

We're living with the consequences of decisions made when our grandparents were young. The pesticides that seemed like pure benefit in the 1950s cast a shadow that extends well into the 21st century and beyond. This should humble us as we consider what persistent legacies our current chemical choices might leave for future generations.

The organochlorine story teaches uncomfortable lessons about persistence, interconnection, and the true cost of short-term solutions. These chemicals solved immediate problems - crop pests, disease vectors - while creating slow-motion disasters that unfold across decades and continents. The full impact remains unclear because we're still in the middle of the experiment.

Since bans took effect, organochlorine levels in human tissues have declined substantially, but the chemicals remain widespread and will continue cycling through food chains for the rest of this century at minimum.

What happens over the next fifty years depends partly on our continued exposure to legacy contamination, but also on whether we've learned anything from this experience. The Stockholm Convention and similar frameworks represent our recognition that some chemicals are simply too persistent, too bioaccumulative, and too toxic to justify their use. Yet new persistent chemicals continue to be developed and deployed, creating potential future analogues to the organochlorine problem.

The encouraging news is that reduction works. Since bans took effect, organochlorine levels in human tissues have declined substantially in monitored populations. Cleanup efforts at contaminated sites reduce local exposure. International cooperation has slowed or halted the addition of new POPs to the environment. These aren't victories - the chemicals remain widespread - but they're progress.

The discouraging news is how slowly progress comes. We're measuring improvement in decades and generations rather than years. The organochlorines already distributed through global ecosystems will continue cycling through food chains for the rest of this century at minimum. New human beings born today will inherit a chemical burden created before their grandparents were born.

Perhaps the deepest lesson is about the illusion of control. We thought we could spray these chemicals precisely where we wanted them, achieve our goals, and move on. Instead, we learned that the planet is one interconnected system. What we release in one place doesn't stay there. What we assume will break down sometimes doesn't. And what we think affects only pests can travel up food chains to affect every organism, including ourselves.

Your dinner tonight probably contains molecules from pesticides banned half a century ago. That's not speculation or fear-mongering - it's documented fact. The question isn't whether we're exposed, but what we do with that knowledge. We can ignore it, accepting persistent contamination as the unavoidable price of modern life. Or we can treat it as a wake-up call about the long-term consequences of short-sighted chemical use.

The chemicals in our food chains are asking us a question: What are we willing to do to protect future generations from inheriting yet another persistent problem we created and couldn't fully solve?

Triton, Neptune's largest moon, orbits backward at 4.39 km/s. Captured from the Kuiper Belt, tidal forces now pull it toward destruction in 3.6 billion years.

Banned pesticides like DDT persist in food chains for decades, concentrating in fatty fish and dairy products, then accumulating in human tissues where they disrupt hormones and increase health risks.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

Humans systematically overestimate how single factors affect future happiness while ignoring broader context - a bias called the focusing illusion. This cognitive flaw drives poor decisions about careers, purchases, and relationships, and marketers exploit it ruthlessly. Understanding this bias and adopting systems-based thinking can improve decision-making, though awareness alone doesn't eliminate the effect.

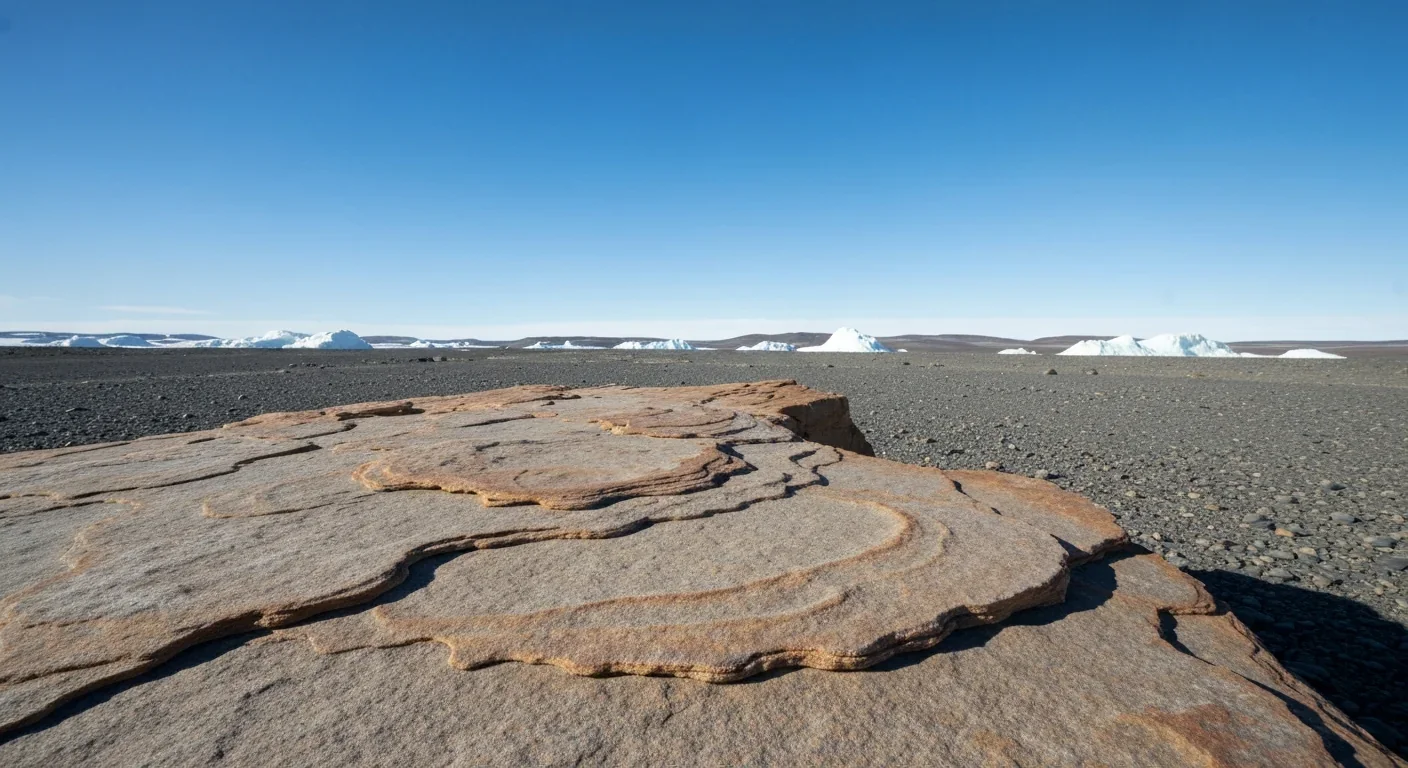

Scientists have discovered lichens living inside Antarctic rocks that survive extreme cold, radiation, and desiccation - conditions remarkably similar to Mars. These cryptoendolithic organisms grow just micrometers per year, can live for thousands of years, and have remained metabolically active in Martian simulations, offering profound insights into life's limits and the potential for extraterrestrial biology.

The nonprofit sector has grown into a $3.7 trillion industry that may perpetuate the very problems it claims to solve by professionalizing poverty management and replacing systemic reform with temporary relief.

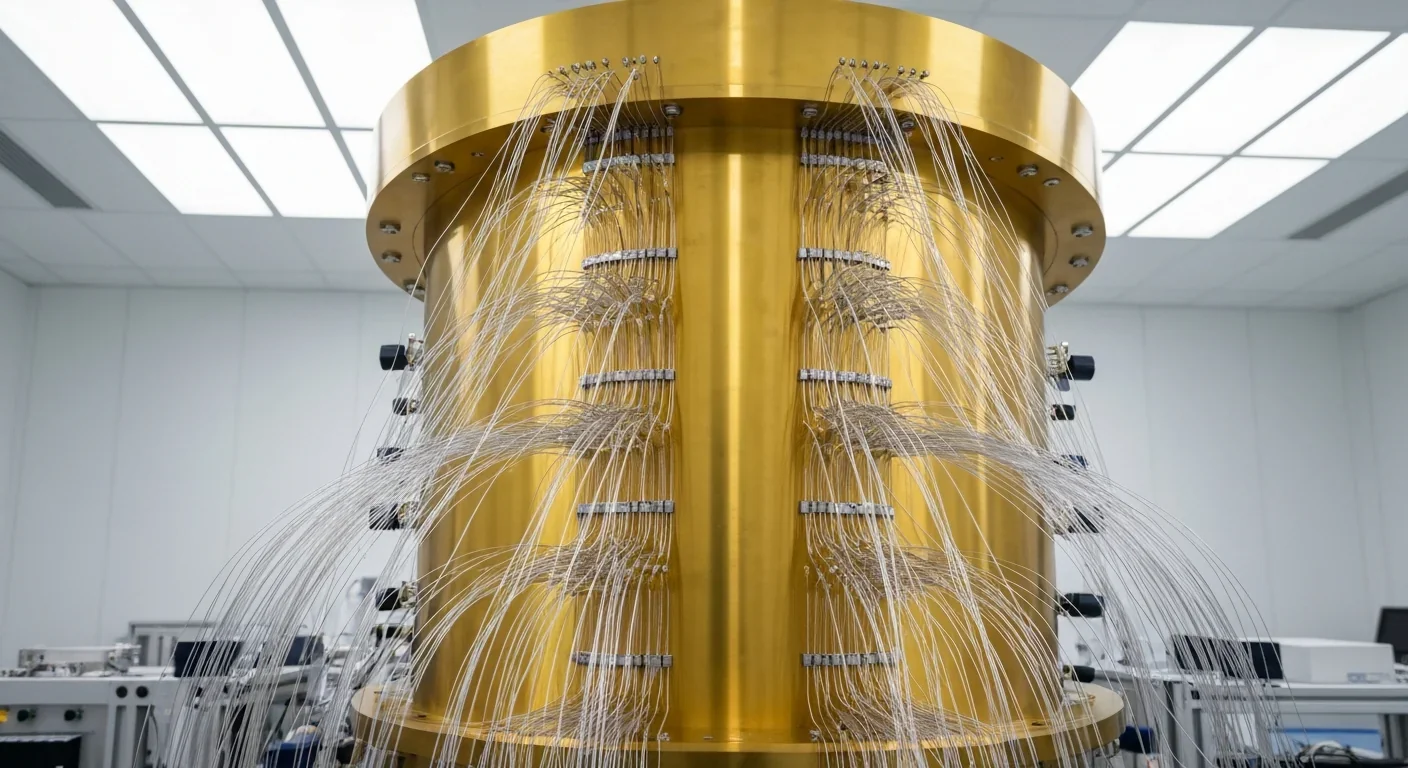

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.