The Ancient Protein Clock That Ticks Without DNA

TL;DR: Nearly 3 million farmworkers suffer organophosphate pesticide poisoning annually, causing irreversible brain damage through acetylcholinesterase inhibition. Despite overwhelming evidence of neurotoxicity and safer alternatives, regulatory failures and industry lobbying allow continued use, creating a hidden epidemic of neurological harm.

Every year, nearly 3 million agricultural workers experience acute organophosphate pesticide poisoning, and more than 200,000 die from the exposure. But these dramatic numbers mask something worse: the millions more who survive face silent, irreversible neurological damage that accumulates with each shift in the fields. The people who grow the food on your table are losing their ability to think, move, and function because of chemicals designed to kill insects by attacking their nervous systems. And those same chemicals do exactly the same thing to human brains.

In a groundbreaking 2025 study, researchers at Columbia University tracked 270 children from birth to age 14 and found something chilling: every single one had detectable levels of chlorpyrifos, a common organophosphate pesticide, in their umbilical cord blood. These children, all born to Latino and African-American mothers in New York City, showed persistent brain abnormalities and motor deficits that didn't fade over time. They were permanent.

The damage starts at the molecular level and radiates outward. What we're learning now is that the effects of these chemicals reach far beyond the fields where they're sprayed, touching communities, contaminating water, and altering the trajectory of children's lives before they even take their first breath.

To understand why organophosphates are so dangerous, you need to understand how your nervous system communicates. Every thought, every movement, every heartbeat depends on chemical messengers called neurotransmitters that jump across tiny gaps between nerve cells. One critical neurotransmitter is acetylcholine, which tells your muscles when to contract, your heart when to beat, and your brain how to process information.

Normally, an enzyme called acetylcholinesterase rapidly breaks down acetylcholine after it delivers its message, resetting the system for the next signal. This happens millions of times per second throughout your body. It's the on-off switch that keeps everything running smoothly.

Organophosphate pesticides permanently disable this switch. When chlorpyrifos enters the body, it's metabolized into chlorpyrifos-oxon, a compound that binds irreversibly to acetylcholinesterase. The enzyme can't break down acetylcholine anymore, so the neurotransmitter floods the nervous system like a river that's burst its banks. Nerve cells fire continuously, receiving signals they can't turn off.

In insects, organophosphates cause paralysis and death within hours. In humans, the effects depend on dose and duration - but chronic low-level exposure slowly rewires the brain in ways we're only beginning to understand.

In insects, this causes paralysis and death within hours. In humans, the effects depend on the dose and duration of exposure. Acute high-dose poisoning causes a cascade of symptoms: excessive salivation, tears, and sweating; muscle twitching and weakness; nausea and diarrhea; difficulty breathing. In severe cases, workers experience seizures, lose consciousness, and suffocate as their respiratory muscles fail.

But most farmworkers never experience acute poisoning. They experience something arguably worse: chronic low-level exposure that slowly rewires their brains.

Farmworker communities have been sounding the alarm for decades, describing headaches, confusion, memory problems, and difficulty concentrating after pesticide exposure. For years, these symptoms were dismissed as temporary, attributed to heat exhaustion or fatigue. Researchers now know the workers were right.

A 2012 study found that even low-level organophosphate exposure damages the brain and nervous system in ways that don't show up on standard cholinesterase tests. Brain imaging revealed structural changes: altered gray matter density, abnormal white matter development, disrupted metabolic activity. These weren't subtle changes. They were widespread throughout the brain.

The Columbia University research pushed this understanding further. Children with higher prenatal exposure to chlorpyrifos showed pronounced differences in brain structure and function that persisted into adolescence. Their motor coordination was slower, their processing speed reduced. Brain scans showed metabolic disturbances across multiple regions involved in movement, cognition, and emotional processing.

What's terrifying is that these children weren't directly exposed. Their mothers were. Chlorpyrifos crosses the placental barrier easily, reaching the developing fetus during the most vulnerable period of brain development. The damage is done before birth, setting children on a trajectory toward lifelong neurological deficits.

"Current widespread exposures continue to place farm workers, pregnant women, and unborn children in harm's way."

- Dr. Virginia Rauh, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

For adult farmworkers, the picture is equally grim. A Frontiers in Public Health study examined pesticide applicators and found clear correlations between organophosphate exposure and impaired cognitive performance. Workers who didn't use adequate protective equipment showed measurable deficits in memory, attention, and executive function compared to unexposed populations.

These deficits compound over years. A farmworker in their twenties might notice occasional brain fog. By forty, they're struggling with tasks that used to be automatic. By sixty, some face early-onset dementia that doctors struggle to distinguish from Alzheimer's disease.

The neurological damage doesn't stop with cognition. Mounting evidence links pesticide exposure to Parkinson's disease, a degenerative disorder that causes tremors, rigidity, and progressive loss of motor control.

Farmers and agricultural workers develop Parkinson's at significantly higher rates than the general population. Research suggests organophosphates may damage the dopamine-producing neurons in a brain region called the substantia nigra, the same cells that die in Parkinson's disease. The chemicals may also trigger oxidative stress and inflammation that accelerates neurodegeneration.

What makes this particularly cruel is the time lag. A farmworker exposed in their twenties might not develop Parkinson's symptoms until their sixties or seventies. By then, decades have passed, making it nearly impossible to prove causation or secure compensation. The damage was done silently, cell by cell, year by year.

Some workers face genetic vulnerabilities that amplify the risk. Variations in the paraoxonase-1 (PON1) enzyme affect how efficiently the body detoxifies organophosphates. People with low PON1 activity can't break down chlorpyrifos-oxon as quickly, leading to higher concentrations in the brain and more severe damage. Children with these genetic variants, born to exposed mothers, face the highest risk of developmental delays and cognitive impairment.

This genetic variation has profound implications for occupational safety. Standard exposure limits assume everyone metabolizes pesticides the same way, but that's not true. Some workers are exponentially more vulnerable, and current regulations don't account for this variation.

Walk through agricultural regions in California, India, Kenya, or Brazil, and you'll find the same story playing out. Workers enter fields shortly after pesticide application, breathe contaminated air, touch treated plants, eat lunch with unwashed hands. They bring pesticide residues home on their clothes and skin, exposing their families to the same toxins.

In Trinidad and Jamaica, a Frontiers study documented alarming rates of unintentional acute pesticide poisoning among smallholder vegetable farmers. Many didn't recognize early symptoms or seek treatment until neurological damage was severe. The researchers found widespread misuse of highly toxic pesticides, inadequate protective equipment, and poor understanding of safe handling practices.

The numbers are staggering. An estimated 3 million organophosphate poisonings occur worldwide annually, concentrated in low- and middle-income countries where regulations are weak and enforcement is nonexistent. Parathion and methylparathion, two of the most toxic organophosphates, cause the majority of occupational poisoning deaths.

Yet these statistics capture only the most dramatic outcomes. For every worker who dies or is hospitalized with acute poisoning, dozens more suffer chronic exposure that degrades their neurological function over decades. These cases never make it into official statistics because the workers don't die suddenly. They just gradually lose the ability to think clearly, move normally, and live independently.

The regulatory story of chlorpyrifos is a masterclass in how industry influence can override public health. In 2001, the EPA banned chlorpyrifos for residential use after determining it posed unacceptable risks to children. But the agency allowed it to remain in agricultural use, where farmworkers and their families faced even higher exposures.

For years, environmental and health advocates pushed for a complete ban. The science was clear: chlorpyrifos causes brain damage in children, harms farmworkers, and persists in the environment. In 2016, the EPA prepared to revoke all food tolerances for the pesticide, effectively banning it from agriculture.

Then politics intervened. In 2017, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt reversed the ban after meeting with executives from Dow Chemical, the pesticide's manufacturer. The decision ignored the agency's own scientists and sparked a 14-year legal battle that finally ended in 2021 when the EPA announced it would ban chlorpyrifos on food crops.

Industry lobbying delayed the chlorpyrifos ban for more than a decade, even as the EPA's own scientists confirmed it caused brain damage in children. Millions of farmworkers continued to be exposed while the legal battle dragged on.

But implementation has been slow and uneven. Some states like California moved ahead with their own bans, but many others still allow its use. And chlorpyrifos is just one of dozens of organophosphate pesticides in use globally. Farmonaut's 2026 analysis identified ongoing risks from malathion, diazinon, and other compounds with similar mechanisms of action.

The regulatory system is designed to react, not prevent. Pesticides are approved based on industry-funded studies, used for decades, and only banned after overwhelming evidence of harm accumulates. By then, millions of workers have been exposed.

Recent research has uncovered another disturbing layer to this crisis. A 2025 study found that farmworkers with chronic pesticide exposure show significant DNA and cellular damage. Organophosphates don't just inhibit acetylcholinesterase. They also generate reactive oxygen species that damage DNA, triggering mutations and cellular dysfunction.

This DNA damage has cascading effects. It impairs the body's ability to repair other types of cellular injury, accelerates aging, and increases cancer risk. Workers exposed to pesticides over decades show elevated rates of lymphomas, leukemias, and brain tumors.

The cellular damage extends beyond neurons. Organophosphates affect immune system function, making workers more susceptible to infections and inflammatory diseases. They disrupt endocrine systems, interfering with hormones that regulate metabolism, reproduction, and development.

And because DNA damage can be inherited, farmworkers may pass compromised genetic material to their children, perpetuating health problems across generations. We're only beginning to understand these multigenerational effects, but early research suggests the impacts could last decades beyond the initial exposure.

You don't have to work in agriculture to be affected by these pesticides. Pesticide drift occurs when chemicals applied to crops travel through air and water, contaminating nearby schools, homes, and communities.

Studies in California's agricultural Central Valley have documented chlorpyrifos in the air more than a mile from application sites. Children attending schools near treated fields show detectable pesticide levels in their bodies and experience higher rates of asthma, developmental delays, and learning disabilities.

Drift isn't an accident. It's an inherent feature of how pesticides are applied. Wind carries aerosolized droplets, irrigation water moves residues into streams and groundwater, and rain washes chemicals from treated soil into drainage systems that feed drinking water supplies.

The EPA acknowledges drift as a serious problem but has struggled to regulate it effectively. Buffer zones around sensitive areas like schools and residential neighborhoods are often too small to prevent exposure, and enforcement is inconsistent.

Communities near agricultural areas face a constant low-level exposure that regulatory frameworks don't capture. Current safety standards focus on occupational exposure in fields, but they don't account for the cumulative impact on people who live, work, and raise children in proximity to treated crops.

The EPA requires farmworkers who handle pesticides to use personal protective equipment, including respirators, gloves, coveralls, and eye protection. In theory, proper PPE should prevent exposure. In practice, it rarely does.

A Frontiers study on PPE effectiveness found that many workers use inappropriate or poorly maintained equipment. Respirator filters aren't changed regularly, gloves tear and aren't replaced, and coveralls are reused without proper cleaning. Some workers can't afford to replace equipment frequently. Others aren't trained on proper use.

Heat poses another challenge. Agricultural work is physically demanding, often performed in high temperatures. Full protective gear is stifling. Workers make a brutal choice: suffer heat exhaustion and potential heat stroke, or remove protective equipment and risk pesticide exposure.

"The focus on personal protective equipment shifts responsibility from pesticide manufacturers to workers themselves. When someone gets sick, the question becomes 'were you wearing your equipment properly?' rather than 'why are we using chemicals that require military-grade protection?'"

- Farmworker health and safety analysis

And PPE only addresses direct contact during application. It doesn't protect against residues on crops during harvesting, pesticides in irrigation water, or drift from nearby fields. A farmworker can follow every safety protocol and still be exposed multiple times daily.

The focus on PPE also shifts responsibility from pesticide manufacturers and agricultural employers to workers themselves. When someone gets sick, the question becomes "were you wearing your equipment properly?" rather than "why are we using chemicals that require military-grade protection?"

The frustrating reality is that we don't need organophosphate pesticides. Safer alternatives exist, including biopesticides derived from natural materials, microbial pesticides that target specific pests, and integrated pest management strategies that reduce reliance on chemical controls.

Biopesticides like pyrethrins (extracted from chrysanthemum flowers) and neem oil have insecticidal properties with far lower toxicity to humans. Microbial pesticides use bacteria, fungi, or viruses that infect target pests but don't harm other organisms. These tools aren't perfect, but they dramatically reduce the risk of neurological damage.

Integrated pest management (IPM) takes a systems approach: crop rotation to break pest cycles, beneficial insects that prey on agricultural pests, physical barriers, and careful monitoring to apply pesticides only when necessary and at the lowest effective dose. Farms that adopt IPM often reduce pesticide use by 50% or more without sacrificing yields.

Organic agriculture eliminates synthetic pesticides entirely, relying on natural pest control methods and soil health to produce crops. Study after study shows that organic farmworkers have lower pesticide exposure and better health outcomes than workers on conventional farms.

So why hasn't the transition happened? Economics, inertia, and lobbying. Conventional pesticides are cheap and easy to use. Transitioning to alternatives requires upfront investment in new equipment, training, and changed practices. Large agricultural companies profit from pesticide sales and fund lobbying efforts to maintain the status quo.

Protecting farmworkers from organophosphate neurotoxicity requires systemic change at every level.

First, we need regulatory reform that prioritizes prevention over reaction. Instead of waiting decades for proof of harm, regulatory agencies should adopt a precautionary approach: if a pesticide shows evidence of neurotoxicity in animal studies, it shouldn't be approved for use until proven safe. The burden of proof should rest with manufacturers, not with workers who suffer the consequences.

Second, enforcement must improve dramatically. CDC and state pesticide illness surveillance programs document thousands of exposure cases annually, but most go unreported. Farms that violate safety regulations face minimal penalties, if any. Strengthening enforcement and imposing meaningful consequences for violations would create real incentives for compliance.

Third, we need to support the transition to safer pest control methods. Government programs could subsidize IPM adoption, fund research on biopesticides and regenerative agriculture, and provide technical assistance to farmers making the shift. Making safer methods economically viable is essential.

Fourth, farmworker rights and protections must be strengthened. Workers need the right to refuse unsafe work without fear of retaliation, access to regular health monitoring, and compensation when exposure causes injury. Many farmworkers are undocumented immigrants with limited legal protections, making them especially vulnerable to exploitation.

Fifth, better tracking and research are essential. California's pesticide illness surveillance system is considered the most comprehensive in the U.S., but even it captures only a fraction of exposures. Expanding surveillance nationwide and funding long-term studies on chronic low-level exposure would provide the data needed to inform policy.

Finally, transparency matters. Consumers have a right to know what pesticides were used on their food and what risks they pose. Clear labeling and public databases would empower people to make informed choices and create market pressure for safer farming practices.

We've built a global food system that depends on poisoning the people who grow our crops. Every time you buy conventionally grown produce, you're participating in an economy that treats farmworker health as an acceptable externality, a cost of doing business that shows up on no balance sheet.

The researchers who tracked those 270 children didn't just find brain abnormalities. They found a moral failure. Dr. Virginia Rauh, one of the study's lead scientists, put it bluntly: "Current widespread exposures continue to place farm workers, pregnant women, and unborn children in harm's way."

Think about that. We have decades of research proving that organophosphates cause irreversible brain damage. We know which populations are most affected. We have safer alternatives. And yet millions of workers continue to be exposed because regulatory systems move slowly and economic interests resist change.

The brain damage from organophosphate exposure is invisible until it's not. Until a worker starts forgetting things at age 45. Until a child struggles in school for reasons no one can explain. Until a 60-year-old farmworker develops Parkinson's and can no longer work.

The brain damage is invisible until it's not. Until a worker starts forgetting things at age 45. Until a child struggles in school for reasons no one can explain. Until a 60-year-old farmworker develops Parkinson's disease and can no longer work.

These outcomes aren't inevitable. They're choices we make as a society: choices about what level of harm we're willing to inflict on vulnerable populations in exchange for cheap, abundant food.

In May 2025, the EU listed chlorpyrifos as a persistent organic pollutant under the Stockholm Convention, joining PCBs and DDT as chemicals that pose such severe environmental and health risks that they warrant global action. This designation marks a turning point, acknowledging that organophosphate damage isn't just a workplace safety issue. It's an international environmental crisis.

Some regions are showing what's possible when political will aligns with public health. California's 2020 ban on chlorpyrifos eliminated one of the most widely used neurotoxic pesticides in the state. UC Berkeley researchers documented measurable improvements in air quality near agricultural areas within months of the ban.

Voices across the U.S. are demanding similar action, organizing farmworkers, public health advocates, and parents to pressure regulatory agencies and elected officials. These grassroots movements are building the political pressure needed to overcome industry lobbying.

Agricultural workers deserve the same protections afforded to other occupations. We don't allow construction workers to operate without fall protection, or factory workers to handle toxic chemicals without safeguards. Why should farmworkers be any different?

The transition won't happen overnight, but every delay means more workers suffering irreversible neurological damage, more children born with preventable developmental deficits, more families losing breadwinners to degenerative diseases.

We know what needs to be done. Ban the most toxic organophosphates immediately. Accelerate the shift to safer alternatives. Strengthen worker protections and enforcement. Fund research on chronic exposure effects. Support communities affected by pesticide drift.

The question isn't whether we can afford to make these changes. It's whether we can afford not to. The true cost of organophosphate pesticides isn't measured in application expenses or crop yields. It's measured in damaged brains, broken bodies, and lives cut short.

That cost is too high. The people who feed us deserve better.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

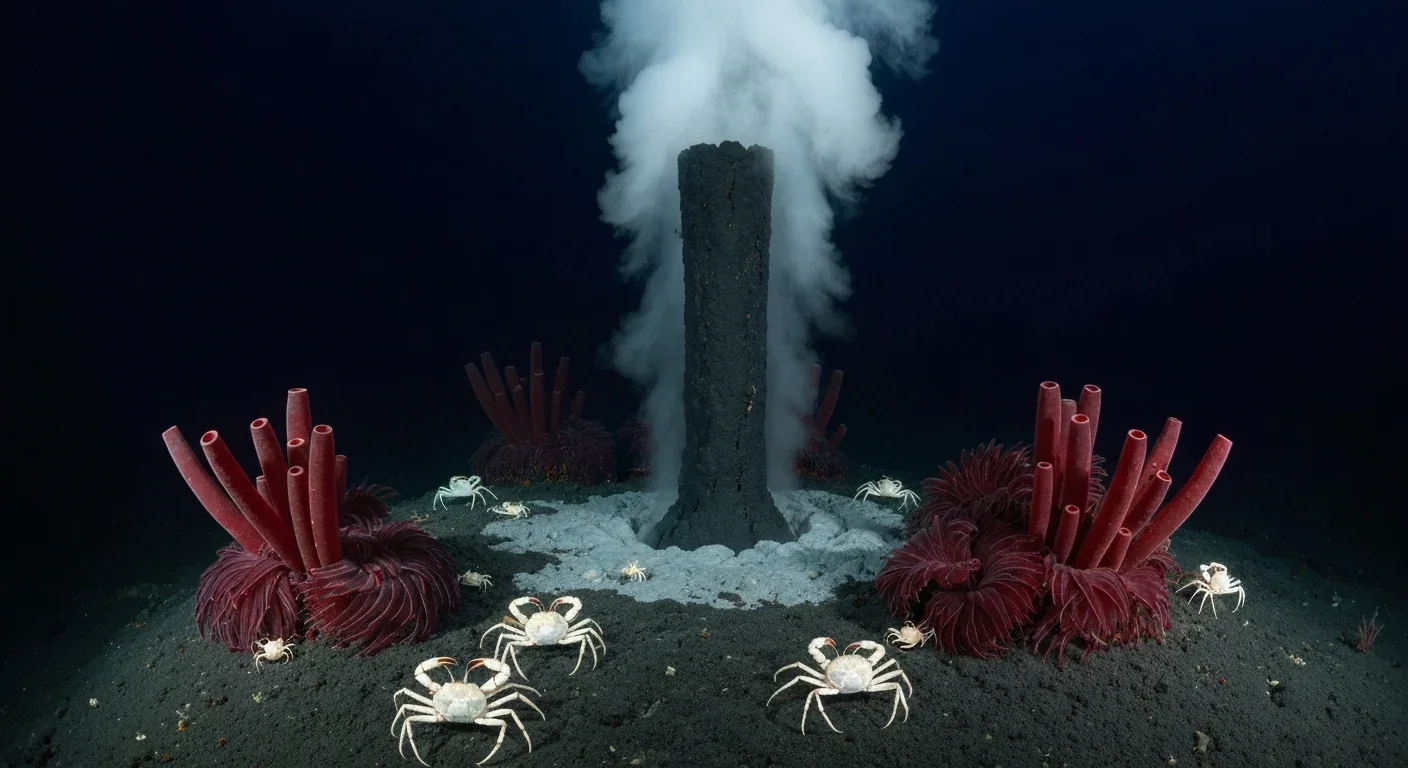

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

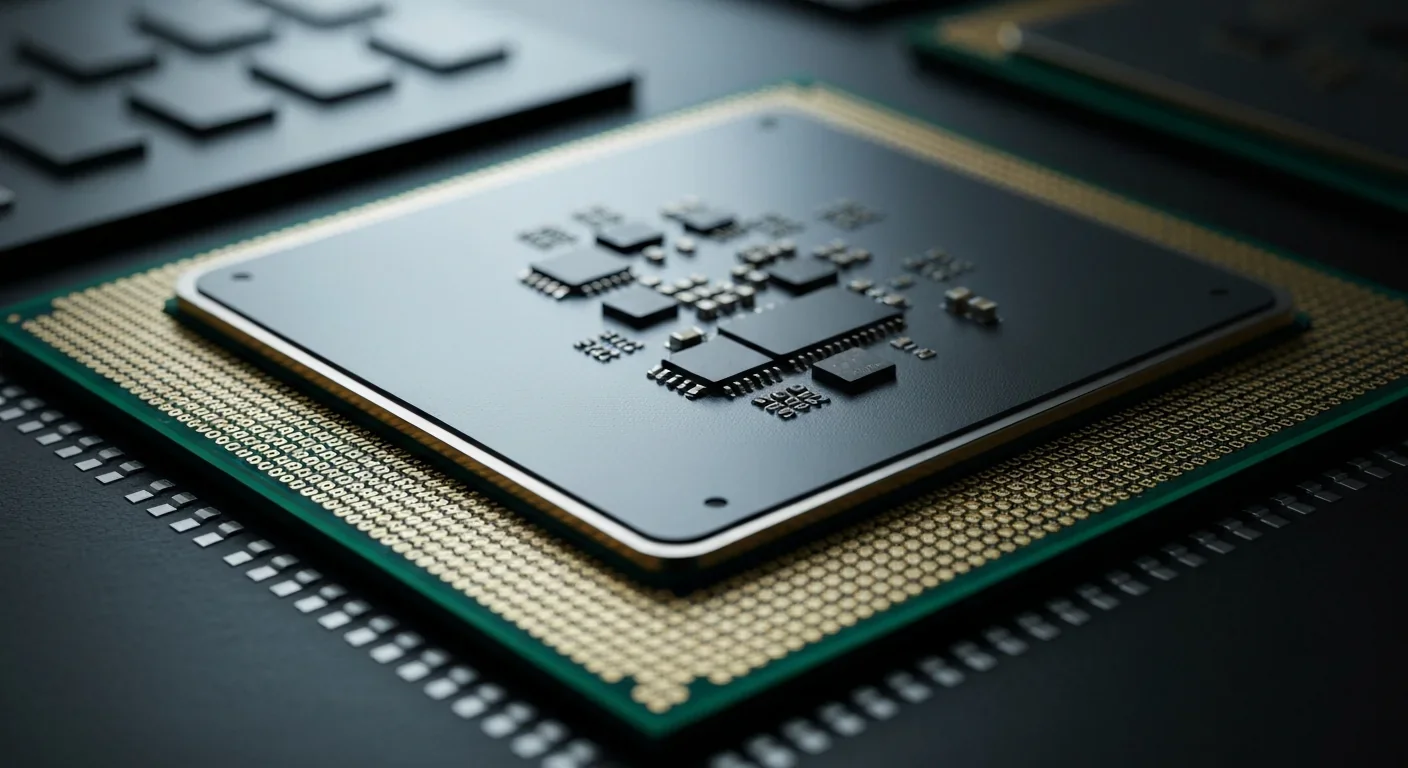

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.