Banned Pesticides Still Contaminate Our Food Chain Today

TL;DR: Cells monitor ribosome production through a surveillance system that can either kill damaged cells or inadvertently create cancer. Understanding this molecular checkpoint is revealing new cancer therapies and explaining rare genetic disorders.

Every second, your cells manufacture roughly 2,000 new proteins. This industrial-scale production happens inside microscopic machines called ribosomes, the protein factories that translate genetic instructions into the molecular workers your body needs to survive. But what happens when these factories malfunction? Recent research reveals a fascinating biological paradox: the same cellular stress response that normally kills damaged cells can sometimes create cancer instead.

This isn't just academic curiosity. Scientists are discovering that understanding how cells respond to ribosomal dysfunction could unlock new cancer treatments, explain rare genetic disorders, and reveal fundamental principles about how life maintains quality control at the molecular level.

Your cells have evolved an elegant quality control mechanism to detect when ribosome production goes wrong. Think of it like a factory that monitors not just the products rolling off assembly lines but the assembly lines themselves. When ribosome biogenesis becomes disrupted - whether from genetic mutations, UV radiation, or cellular stress - a cascade of molecular signals activates what researchers call the ribosomal stress response.

The key player in this surveillance system is p53, often called the "guardian of the genome." This tumor suppressor protein normally gets degraded by two regulatory proteins, MDM2 and MDM4, which keep p53 levels low during normal conditions. But when ribosome production falters, something remarkable happens.

Specific ribosomal proteins - particularly RPL5 and RPL11 - escape from the nucleolus, the cell's ribosome-building factory, and form a complex with 5S ribosomal RNA. This complex, known as the 5S RNP, binds directly to MDM2 and blocks its ability to degrade p53. The result? p53 levels surge, triggering cell cycle arrest or programmed cell death.

It's a protective mechanism that usually works beautifully, eliminating potentially damaged cells before they can cause problems. But like any biological system, it's not foolproof.

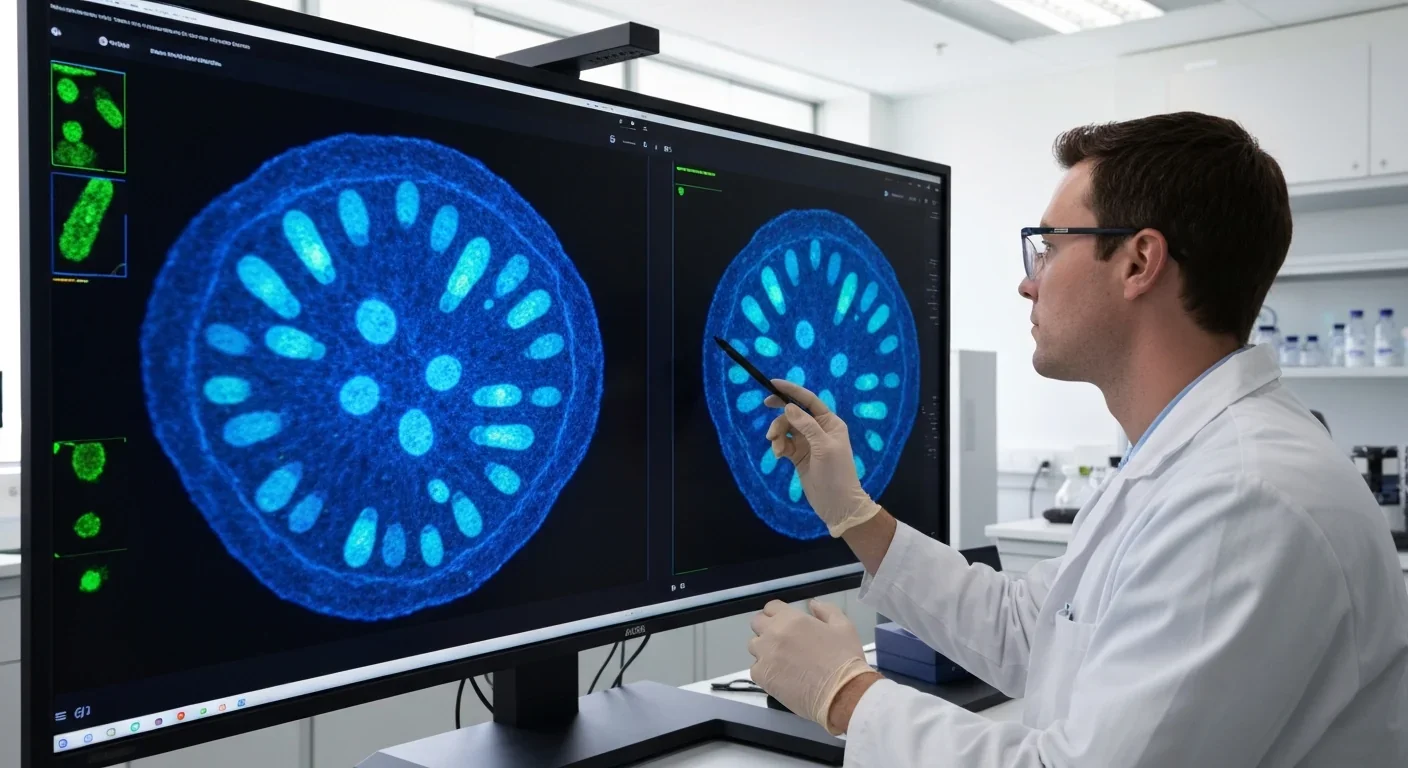

When ribosome production fails, free ribosomal proteins activate p53 by blocking its normal degradation pathway - a quality control mechanism that can either prevent cancer or, paradoxically, contribute to it.

Here's where things get complicated. The ribosomal stress response that's supposed to prevent cancer can actually cause it under certain circumstances. This paradox becomes visible in a group of rare genetic disorders called ribosomopathies.

Take Diamond-Blackfan anemia, a condition where mutations in ribosomal protein genes disrupt red blood cell production. Patients experience severe anemia because their blood cell precursors can't produce enough ribosomes and undergo p53-mediated cell death. Yet paradoxically, people with Diamond-Blackfan anemia face elevated cancer risk, particularly for leukemia and solid tumors.

Treacher Collins syndrome presents another example. Mutations in the TCOF1 gene impair ribosome biogenesis during embryonic development, causing severe facial abnormalities. The condition arises because neural crest cells - which form facial bones and cartilage - are particularly sensitive to ribosomal stress and die via p53-dependent apoptosis.

The emerging picture suggests that chronic ribosomal dysfunction creates evolutionary pressure. Most affected cells die, but occasionally, some accumulate additional mutations that allow them to bypass p53 surveillance. These survivors become cancer cells, having learned to tolerate or exploit ribosomal stress.

Recent research has identified that ribosomal protein deficiencies activate not just p53 but also ATF4, a stress response transcription factor. This creates a more complex signaling landscape where cells must integrate multiple stress signals to decide between survival, adaptation, or death.

The question becomes: what determines whether ribosomal stress kills a cell or transforms it into cancer? Scientists have discovered this isn't a simple on/off switch but rather a nuanced decision tree influenced by several factors.

First, the severity and duration of ribosomal stress matters. Acute, severe disruption typically triggers rapid p53 activation and cell death. But chronic, moderate stress may allow cells to adapt, potentially selecting for mutations that inactivate p53 or its downstream targets.

Second, the cellular context matters enormously. Research on nucleolar stress shows that the nucleolus functions as a stress sensor hub, integrating signals from ribosome biogenesis with other cellular stresses like nutrient deprivation, DNA damage, and oncogene activation. The nucleolus can sequester regulatory proteins and generate non-coding RNAs that modulate cell fate decisions.

Third, not all ribosomal proteins act identically. While RPL5 and RPL11 primarily work through the classical MDM2-p53 pathway, other ribosomal proteins have distinct functions. RPL22, for instance, regulates alternative splicing of MDM4, creating a parallel pathway to activate p53. This suggests redundancy in the surveillance system but also potential vulnerabilities that cancer cells might exploit.

The tumor suppressor protein HNRNPK adds another layer of complexity. Recent studies show HNRNPK induces p53-dependent nucleolar stress to drive ribosomopathies, suggesting that some genetic defects deliberately trigger ribosomal stress as a pathological mechanism rather than responding to it.

"Cellular responses to ribosome biogenesis inhibition extend beyond general alterations in transcription and translation to actively determine cancer cell fate by selectively engaging tumor-suppressor pathways."

- Research on ribosomal protein regulation of p53

While ribosomal stress can kill normal cells, cancer cells often have a complicated relationship with their protein factories. Most cancer cells actually increase ribosome production to support their rapid growth. This creates both a vulnerability and an opportunity for treatment.

Cancer cells frequently harbor mutations that increase ribosome biogenesis, driven by oncogenes like MYC that upregulate ribosomal RNA transcription. They need massive amounts of protein synthesis to sustain rapid division and growth. This ribosomal addiction makes them particularly sensitive to drugs that target ribosome production.

Several experimental cancer therapies exploit this vulnerability by deliberately inducing ribosomal stress in tumor cells. CX-5461, for example, inhibits RNA polymerase I, the enzyme that transcribes ribosomal RNA genes. In preclinical studies, this triggers p53 activation and selectively kills cancer cells while sparing most normal cells.

The strategy gets even more sophisticated. Some cancers have already lost p53 function through mutation - roughly half of all human cancers carry p53 mutations. For these tumors, inducing ribosomal stress won't trigger the classical apoptotic pathway. Instead, researchers are exploring p53-independent mechanisms by which ribosomal dysfunction can still kill cells, including activation of alternative cell death pathways.

Research has shown that ribosomal stress can activate autophagy, interfere with cell cycle progression, and trigger inflammatory responses even without functional p53. This suggests multiple therapeutic angles for targeting the ribosomal stress response.

The genetic landscape of ribosomal dysfunction in cancer proves surprisingly complex. While ribosomopathies typically involve germline mutations in ribosomal protein genes, cancer-associated ribosomal mutations show different patterns.

Many cancers carry mutations in nucleolar proteins that regulate ribosome assembly rather than in ribosomal proteins themselves. Nucleophosmin (NPM1), for instance, is the most frequently mutated gene in acute myeloid leukemia. NPM1 normally coordinates ribosome assembly in the nucleolus, but mutant versions mislocalize to the cytoplasm, disrupting nucleolar architecture and ribosome production.

Other cancers exploit ribosomal stress through epigenetic mechanisms. Changes in ribosomal DNA methylation patterns can alter ribosome production rates, creating heterogeneous populations of cells with varying stress resistance. This heterogeneity may help tumors survive therapy and develop resistance.

Recent genomic studies have revealed that even subtle variations in ribosome composition - different combinations of ribosomal protein isoforms - can affect which mRNAs get translated preferentially. This "ribosome code" hypothesis suggests cancer cells might customize their ribosomes to preferentially translate oncogenic proteins while avoiding tumor suppressors.

The therapeutic implication? Different cancers might require personalized approaches based on their specific ribosomal alterations and p53 status.

Cancer cells don't just tolerate ribosomal stress - they become addicted to increased ribosome production to fuel their rapid growth, creating a therapeutic vulnerability that drugs can exploit.

One surprising insight into ribosomal stress comes from sun exposure. UV radiation damages not just DNA but also actively transcribed ribosomal RNA genes. When UV photons strike skin cells, they create lesions that stall RNA polymerase I on ribosomal DNA, triggering what researchers call "ribosome roadblocks."

These roadblocks activate the ribosomal stress response through multiple mechanisms. Stalled polymerases recruit DNA damage sensors, disrupted ribosome biogenesis releases free ribosomal proteins to activate p53, and nucleolar integrity becomes compromised. The result is rapid apoptosis of severely damaged skin cells - your skin's way of preventing UV-induced cancers.

This explains why sunburns cause skin peeling. The cells dying and shedding have activated ribosomal stress pathways in response to irreparable UV damage. It's a protective mechanism, though imperfect - some damaged cells inevitably escape elimination and may later develop into melanomas or other skin cancers.

The UV research also revealed that ribosomal stress pathways respond not just to reduced ribosome quantity but to reduced quality. Damaged ribosomes that misincorporate amino acids or stall during translation trigger similar surveillance mechanisms, suggesting cells monitor translation fidelity as carefully as translation capacity.

Understanding the ribosomal stress response requires appreciating the central role of MDM2 and MDM4, the two proteins that normally keep p53 in check. These proteins function as the gatekeepers between life and death in stressed cells.

MDM2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that tags p53 for degradation by the proteasome. It also has non-enzymatic functions, binding to p53's transactivation domain to prevent it from activating target genes. MDM4 (also called MDMX) lacks ligase activity but enhances MDM2 function and independently suppresses p53.

The ribosomal stress response disrupts this regulatory axis through multiple mechanisms. The 5S RNP complex formed by RPL5, RPL11, and 5S rRNA physically binds MDM2, blocking its interaction with p53. Meanwhile, RPL22 alters MDM4 splicing, producing an isoform that cannot suppress p53 effectively.

Recent structural studies have revealed exactly how ribosomal proteins bind MDM2, identifying specific interfaces that could potentially be targeted by drugs. Small molecules that mimic ribosomal protein binding might activate p53 in cancer cells without actually disrupting ribosome function, avoiding the toxicity of blocking ribosome biogenesis systemically.

The MDM2-MDM4 axis also represents a point of dysfunction in ribosomopathies. In Diamond-Blackfan anemia, excessive p53 activation through dysregulated MDM2 causes the characteristic bone marrow failure. Researchers have tested MDM2 activators or p53 inhibitors as potential treatments, with the goal of restoring the balance between cell survival and death.

Beyond the p53 pathway, cells respond to ribosomal stress by reorganizing their entire translation machinery. One visible manifestation is the formation of stress granules, dense cytoplasmic aggregates of stalled translation initiation complexes, mRNAs, and RNA-binding proteins.

Recent research on ribosome association and stress granules shows that actively translating ribosomes actually inhibit mRNA localization to stress granules. This creates a sorting mechanism: mRNAs that ribosomes can still translate efficiently remain in the cytoplasm and continue producing proteins, while mRNAs that stall or fail to recruit ribosomes get sequestered in stress granules.

This sorting has profound implications for cell fate. Stress granules can protect specific mRNAs from degradation, creating a reservoir of transcripts that can rapidly resume translation if conditions improve. But prolonged stress granule formation may also promote aggregation of RNA-binding proteins, potentially contributing to neurodegenerative diseases.

Cancer cells manipulate stress granule dynamics to survive therapy. Chemotherapy drugs that induce ribosomal stress trigger stress granule assembly, but cancer cells often upregulate proteins that promote stress granule disassembly, allowing them to resume translation quickly after treatment ends.

The deepening understanding of ribosomal stress responses is opening new therapeutic avenues. Several strategies are under development or in clinical trials.

First, direct inhibitors of ribosome biogenesis show promise for treating cancers with intact p53. Besides CX-5461, which targets RNA polymerase I, researchers are testing compounds that block ribosome assembly factors, disrupt nucleolar structure, or inhibit ribosomal RNA processing. The key challenge is achieving selectivity - cancer cells are more sensitive to these agents than normal cells, but the therapeutic window remains narrow.

Second, targeting the MDM2-p53 axis has produced several drug candidates. Nutlins and similar compounds bind MDM2's p53-binding pocket, preventing MDM2 from degrading p53. These drugs essentially mimic the effect of ribosomal stress without actually disrupting protein synthesis. Early clinical trials show activity against various cancers, particularly those with wild-type p53.

Third, for ribosomopathies like Diamond-Blackfan anemia, the opposite approach is being explored - reducing p53 activation to allow more cells to survive despite ribosomal defects. L-leucine supplementation, which enhances residual protein synthesis capacity, has shown benefit in some patients. Gene therapy to restore missing ribosomal proteins represents a more definitive long-term solution currently under development.

Fourth, researchers are investigating combination approaches that exploit cancer cells' ribosomal vulnerabilities. Pairing ribosome biogenesis inhibitors with drugs targeting alternative survival pathways might prevent the adaptive resistance that limits single-agent efficacy.

A particularly innovative strategy involves targeting cancer-specific ribosome variants. If cancer cells truly customize their ribosomes to preferentially translate oncogenic mRNAs, drugs that specifically interfere with these altered ribosomes might offer exquisite selectivity.

"The ability of some ribosomal proteins to control MDM2 and MDM4 activities, and thereby p53, underscores an intriguing aspect of cell biology where protein synthesis machinery directly regulates cell fate."

- Study on ribosomal proteins in p53 regulation

Stepping back, the ribosomal stress response reveals fundamental principles about how complex biological systems maintain stability while remaining adaptable. Cells can't afford to let protein synthesis run unchecked - the energetic cost and potential for errors are too high. Yet they also can't be too stringent, or they'd destroy themselves over minor fluctuations.

The solution evolution arrived at involves multilayered surveillance: monitoring ribosome quantity through the 5S RNP-MDM2 axis, monitoring ribosome quality through translation fidelity mechanisms, and integrating these signals with other cellular stresses in the nucleolus. Redundancy provides robustness, while the ability to bypass some checkpoints allows adaptation when circumstances demand it.

Cancer exploits this system's flexibility, finding ways to tolerate ribosomal abnormalities that would kill normal cells. Ribosomopathies reveal what happens when the system overreacts, eliminating too many cells and causing tissue failure. Future therapies will need to navigate this narrow path between insufficient and excessive quality control.

The research also highlights how ancient and essential functions - like ribosome production - become cancer vulnerabilities. Ribosomes emerged billions of years ago and remained so critical that their structure barely changed. Cancer's universal need for rapid growth makes ribosome biogenesis an unavoidable dependency, one that's being exploited therapeutically.

As we understand more about how cells sense and respond to ribosomal dysfunction, several questions remain unanswered. What determines whether chronic ribosomal stress leads to cell death, adaptation, or transformation? Can we predict which patients with ribosomopathies will develop cancer based on their specific mutations and cellular responses? How much can we safely disrupt ribosome biogenesis in cancer therapy without causing ribosomopathy-like side effects?

Advanced technologies are helping address these questions. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals how individual cells within a tumor respond differently to ribosomal stress, explaining why some survive treatment. Cryo-electron microscopy structures of stress-sensing complexes guide drug design. Patient-derived organoids allow testing whether ribosome-targeting therapies will work for specific cancers before trying them in people.

Perhaps most intriguingly, ribosomal stress research is converging with other fields to reveal unexpected connections. Links to aging, neurodegeneration, and metabolic diseases keep emerging. The nucleolus, long dismissed as merely the ribosome factory, is being recognized as a signaling hub that coordinates cellular responses to diverse stresses.

We're learning that when your cell's protein factories break down, the consequences ripple through every aspect of cellular function. The response can save your life by eliminating precancerous cells or threaten it by causing cancer or genetic disorders. Understanding this biological paradox might ultimately help us live longer, healthier lives by keeping our cellular quality control systems working just right - vigilant enough to prevent cancer but not so aggressive they destroy healthy tissue.

The protein factories inside your cells operate continuously, producing the molecular machines that keep you alive. When they falter, your cells face an ancient choice between death and transformation. Scientists are finally learning how that choice gets made and how to influence it. What emerges from this research may transform how we treat cancer, understand genetic diseases, and think about cellular health itself.

Triton, Neptune's largest moon, orbits backward at 4.39 km/s. Captured from the Kuiper Belt, tidal forces now pull it toward destruction in 3.6 billion years.

Banned pesticides like DDT persist in food chains for decades, concentrating in fatty fish and dairy products, then accumulating in human tissues where they disrupt hormones and increase health risks.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

Humans systematically overestimate how single factors affect future happiness while ignoring broader context - a bias called the focusing illusion. This cognitive flaw drives poor decisions about careers, purchases, and relationships, and marketers exploit it ruthlessly. Understanding this bias and adopting systems-based thinking can improve decision-making, though awareness alone doesn't eliminate the effect.

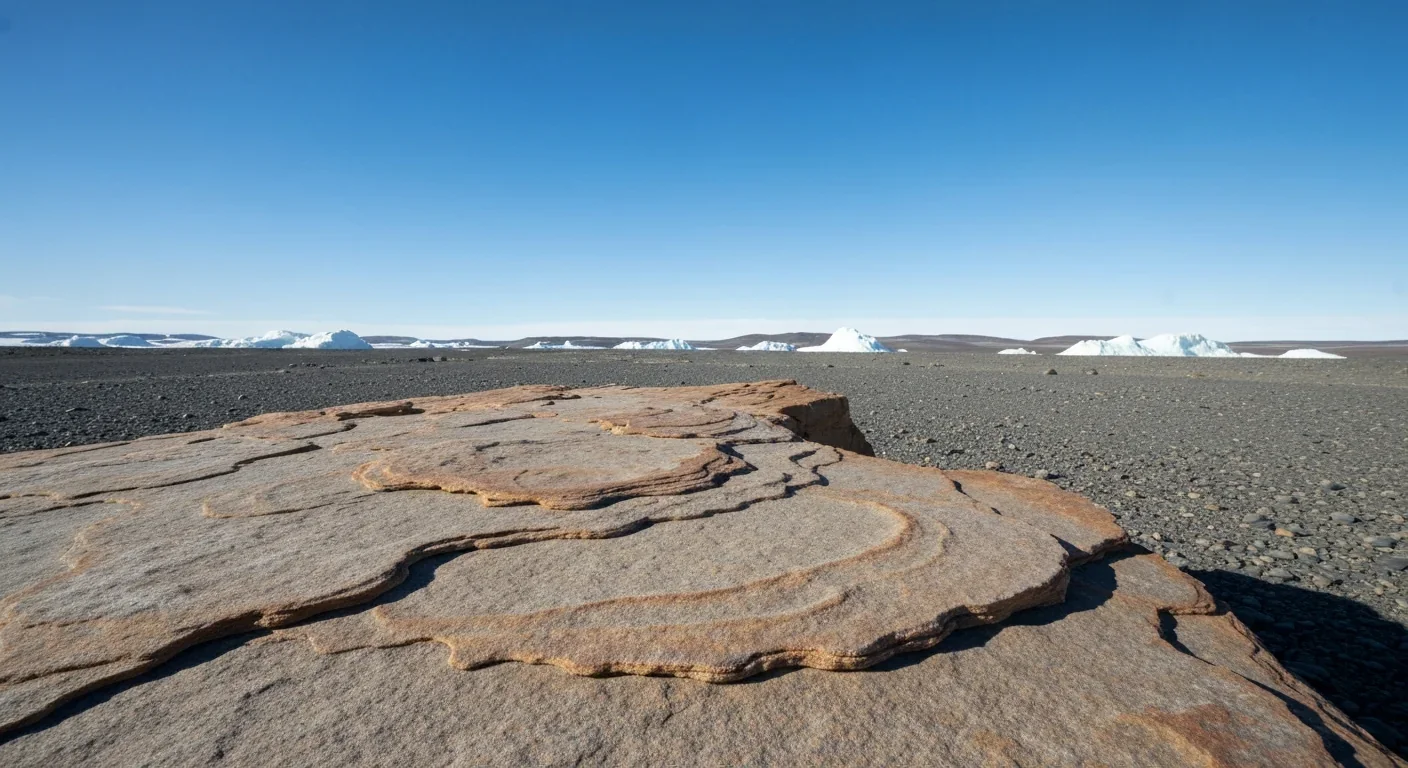

Scientists have discovered lichens living inside Antarctic rocks that survive extreme cold, radiation, and desiccation - conditions remarkably similar to Mars. These cryptoendolithic organisms grow just micrometers per year, can live for thousands of years, and have remained metabolically active in Martian simulations, offering profound insights into life's limits and the potential for extraterrestrial biology.

The nonprofit sector has grown into a $3.7 trillion industry that may perpetuate the very problems it claims to solve by professionalizing poverty management and replacing systemic reform with temporary relief.

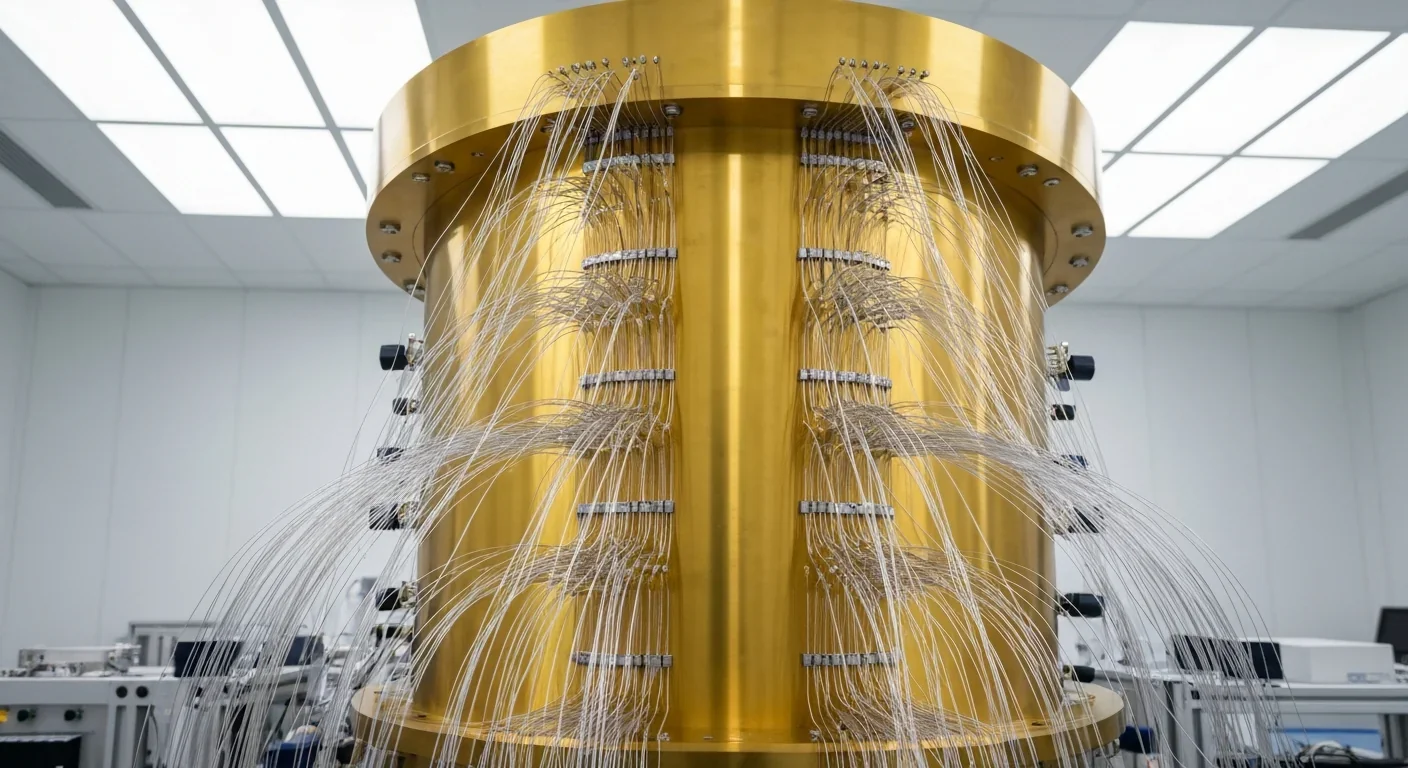

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.