Secret Bacteria That Train Your Baby's Immune System

TL;DR: Gut bacteria transform bile acids into hormone-like molecules that regulate metabolism, immunity, and disease risk. Understanding this hidden endocrine system opens new therapeutic pathways for treating diabetes, obesity, and inflammation.

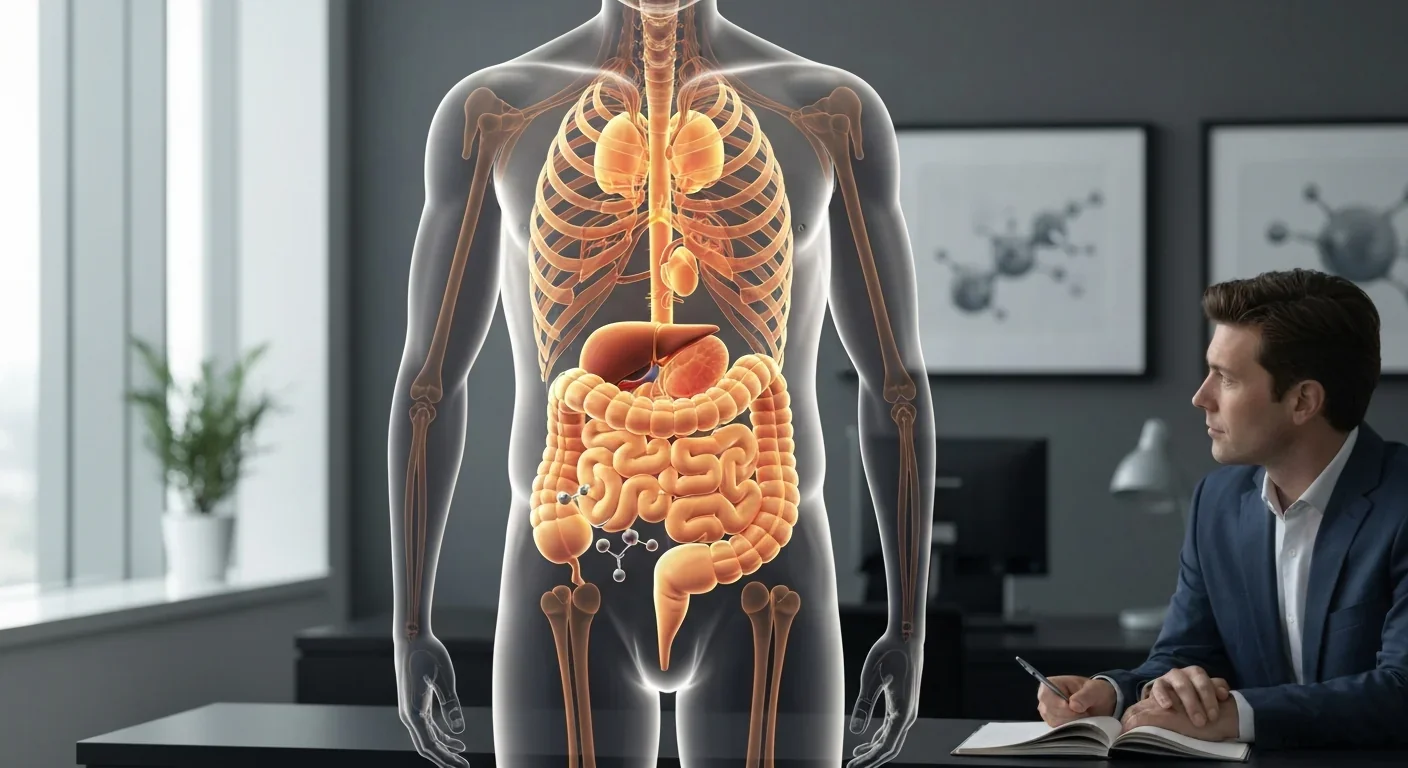

Within your intestines right now, an invisible chemical factory is running at full capacity. Trillions of bacteria are intercepting molecules your liver produced for digestion and transforming them into something completely different: powerful signaling chemicals that function like hormones, affecting everything from blood sugar regulation to cancer risk. This isn't science fiction. It's the bile acid transformation system, and researchers are just beginning to understand how profoundly it shapes human health.

For decades, scientists viewed bile acids as simple digestive detergents, molecules your liver makes from cholesterol to help break down fats. But that understanding collapsed when research teams discovered that gut bacteria chemically modify these molecules into an entirely new class of signaling compounds. These bacterial products activate receptors throughout your body, influencing metabolism, immunity, and inflammation. We've been carrying around a hidden endocrine organ, and it's made of microbes.

Your body produces about 500-600 milligrams of bile acids daily, synthesizing them in the liver from cholesterol through the action of an enzyme called cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase. The liver creates two primary bile acids: cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid. These molecules are conjugated with amino acids to make them more soluble, then secreted into the small intestine to help digest dietary fats.

Here's where it gets interesting. About 95% of these bile acids are reabsorbed in the lower small intestine and returned to the liver through what's called enterohepatic circulation. This recycling loop happens 6-8 times every single day, meaning the same bile acid molecules cycle repeatedly between your liver and gut. It's one of the most efficient recycling systems in human physiology.

But the remaining 5% that escape into the colon encounter something the liver never anticipated: hundreds of bacterial species equipped with specialized enzymes. These microbes don't just tolerate bile acids; they actively transform them. The result is a cascade of chemical modifications that creates over 50 different bile acid species, many of which function as hormone-like signaling molecules your own cells cannot produce.

Your gut microbiome transforms bile acids into over 50 different signaling molecules that your own cells cannot produce, creating a hidden endocrine system.

The transformation begins with an enzyme called bile salt hydrolase, or BSH. Found widely in bacterial species including Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Clostridium, and Eubacterium, BSH acts as a molecular gateway. It breaks the bond between the bile acid and its amino acid conjugate, a process called deconjugation. This seemingly simple reaction is actually the first step in a complex transformation pathway.

Once deconjugated, bile acids become substrates for additional bacterial enzymes. The most important is 7α-dehydroxylase, which removes a hydroxyl group from specific positions on the bile acid molecule. Through this reaction, cholic acid becomes deoxycholic acid, and chenodeoxycholic acid becomes lithocholic acid. These are the major secondary bile acids, and they have very different biological properties than their primary counterparts.

But here's a twist that researchers only discovered recently: BSH enzymes don't just deconjugate bile acids. They also work in reverse, acting as amine N-acyl transferases. This means they can conjugate free bile acids with different amino acids than the liver uses, creating what scientists call microbial conjugated bile acids, or MCBAs. These compounds represent an entirely new chemical space, a class of signaling molecules that didn't exist until bacteria made them.

The diversity is stunning. Beyond the classic secondary bile acids like deoxycholic acid and lithocholic acid, bacteria produce isodeoxycholic acid, ursodeoxycholic acid, and numerous other variants through additional reactions including dehydrogenation, epimerization, and oxidation. Each modification subtly changes the molecule's shape and chemical properties, which in turn affects how it interacts with receptors in human tissues.

The transformed bile acids don't stay in the gut. Many are reabsorbed and enter the bloodstream, where they travel throughout the body. Once in circulation, they activate two major classes of receptors: FXR (farnesoid X receptor) and TGR5 (Takeda G-protein receptor 5).

FXR is a nuclear receptor found primarily in the liver, intestine, and kidneys. When bile acids activate FXR in the liver, they trigger a negative feedback loop that suppresses the enzyme CYP7A1, reducing further bile acid synthesis. This is classic hormonal regulation. In the intestine, FXR activation induces production of a hormone called FGF15 (FGF19 in humans), which travels to the liver and reinforces the signal to stop making more bile acids.

But FXR does more than regulate bile acid production. Its activation influences cholesterol metabolism, triglyceride synthesis, glucose homeostasis, and inflammation. Studies have shown that when BSH activity increases and modifies the bile acid pool composition, it alters FXR signaling, which in turn affects cholesterol levels. Clinical trials with BSH-expressing probiotic strains reduced serum cholesterol by up to 33% in people with high cholesterol.

"Gut microbiota-derived bile salt hydrolase, which catalyzes the 'gateway' reaction in a wider pathway of bile acid modification, not only shapes the bile acid landscape, but also modulates the crosstalk between gut microbiota and host health."

- Frontiers in Microbiology, 2025

TGR5 works differently. It's a G-protein coupled receptor found on cell membranes in multiple tissues, including intestinal cells, muscle, brown adipose tissue, and immune cells. When secondary bile acids like deoxycholic acid activate TGR5, they stimulate energy expenditure, improve insulin sensitivity, and modulate inflammation.

A breakthrough study from researchers at EPFL showed that TGR5 activation on macrophages blocks the chemical signals these immune cells use to recruit more macrophages into fat tissue. This matters because macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue drives the chronic low-grade inflammation associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes. By reducing this inflammatory infiltration, bile acid signaling through TGR5 helps restore insulin sensitivity.

The realization that gut bacteria generate hormone-like bile acid signals has completely reframed our understanding of metabolic disease. Type 2 diabetes, obesity, fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular conditions all show alterations in bile acid profiles. People with these conditions typically have disrupted gut microbiomes and abnormal ratios of primary to secondary bile acids.

Consider what happens when someone takes broad-spectrum antibiotics. The drugs kill many bile-acid-transforming bacteria, dramatically reducing secondary bile acid production. Within days, the bile acid pool composition shifts heavily toward primary bile acids. This disrupts FXR and TGR5 signaling throughout the body, potentially affecting glucose metabolism, lipid processing, and inflammatory tone. Some researchers believe this mechanism partly explains the metabolic side effects occasionally seen with prolonged antibiotic use.

Diet creates equally profound effects. A high-fat diet increases bile acid production because more bile is needed to digest dietary fats. This provides more substrate for bacterial transformation, potentially increasing secondary bile acid production. But diet also shapes the gut microbiome composition, favoring certain bacterial species over others. A diet rich in fiber promotes bacteria like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus that express BSH enzymes, while a low-fiber, high-fat Western diet tends to reduce bacterial diversity and may diminish bile acid transformation capacity.

The complexity deepens when you consider that different bile acids activate receptors with different potencies. Chenodeoxycholic acid is the most potent natural FXR agonist, while deoxycholic acid preferentially activates TGR5. Lithocholic acid, meanwhile, can be toxic at high concentrations and is normally sulfated and excreted. The balance between these molecules, determined partly by which bacterial species are present and active, fine-tunes metabolic signaling.

Clinical trials showed that probiotic strains expressing bile salt hydrolase enzymes reduced serum cholesterol by up to 33% in people with high cholesterol.

Understanding bile acid signaling has opened multiple therapeutic avenues. Drug developers are pursuing several strategies simultaneously, each targeting different points in the pathway.

FXR agonists are the most advanced. Obeticholic acid, a semisynthetic bile acid derivative, received approval for treating primary biliary cholangitis and is being tested for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. By strongly activating FXR, it shifts metabolism in ways that reduce liver inflammation and fibrosis. However, FXR activation also affects cholesterol metabolism in complex ways, and managing side effects has proven challenging.

TGR5 agonists represent another approach. Researchers have identified several small molecules that mimic bile acid activation of TGR5 without the potential toxicity of actual bile acids. These compounds show promise for treating metabolic syndrome by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing inflammation, though none have reached market yet.

Bile acid sequestrants take a different tack. These drugs bind bile acids in the intestine, preventing their reabsorption. This forces the liver to synthesize more bile acids from cholesterol, lowering blood cholesterol levels. But sequestrants also alter the bile acid pool available for bacterial transformation, potentially affecting secondary bile acid production and downstream signaling.

The most innovative approaches target the microbiome directly. Researchers are developing next-generation probiotics engineered to express specific BSH variants or other bile-acid-modifying enzymes. The goal is to rationally reshape the bile acid pool to achieve desired metabolic effects. Some teams are even exploring fecal microbiota transplantation as a way to restore healthy bile acid metabolism in people with metabolic disease.

Live biotherapeutic products containing specific bacterial strains represent a middle ground. Unlike traditional probiotics, these are characterized consortia designed to colonize the gut and perform specific metabolic functions. Several companies are developing bile-acid-focused biotherapeutics for conditions ranging from obesity to inflammatory bowel disease.

The bile acid story extends beyond metabolism. High levels of certain secondary bile acids, particularly deoxycholic acid, are associated with increased colorectal cancer risk. The proposed mechanism involves bile acid damage to intestinal cells and promotion of inflammation, both of which can contribute to cancer development. People with obesity tend to have elevated deoxycholic acid levels, which may partly explain their increased colorectal cancer risk.

Conversely, some bile acids show potential anticancer properties. Ursodeoxycholic acid, a minor secondary bile acid, has anti-inflammatory and protective effects on intestinal cells. It's approved for treating certain liver conditions and is being studied for cancer prevention in high-risk populations.

Bile acids also modulate immune function beyond their effects on macrophages. They influence the balance between inflammatory and regulatory T cells in the gut, affect dendritic cell maturation, and alter the production of inflammatory cytokines. Through these mechanisms, the bacterial transformation of bile acids helps regulate intestinal immunity and maintains the delicate balance between tolerating beneficial microbes while defending against pathogens.

"Bile acids have traditionally been thought to be restricted to the small intestine, helping with the digestion of lipids. But recent studies have shown that bile acids also enter the bloodstream and behave like hormones."

- Dr. Kristina Schoonjans, EPFL

Recent research suggests bile acids may even influence brain function. TGR5 receptors are expressed in brain tissue, and some studies indicate that bile acid signaling affects mood, cognition, and neurodegenerative disease progression. The gut-brain axis may operate partly through bile acid signals, adding another layer to the already complex relationship between gut microbes and mental health.

While therapeutic interventions are still being refined, the existing research offers some practical implications. Your gut bacteria's bile acid transformation capacity is influenced by factors you can control.

Diet matters enormously. Fiber feeds beneficial bacteria that express BSH and other bile-acid-modifying enzymes. Fermented foods provide live bacteria that may contribute to bile acid metabolism. Polyphenols from fruits, vegetables, tea, and coffee affect both the microbiome composition and bile acid signaling pathways directly.

Exercise influences bile acid metabolism too, though the mechanisms are still being worked out. Physical activity alters gut microbiome composition, affects bile acid synthesis rates, and modifies how tissues respond to bile acid signals. Studies in mice show that exercise training changes the bile acid profile in ways that improve metabolic health.

Circadian rhythms add yet another variable. Both bile acid synthesis in the liver and bacterial metabolic activity in the gut follow daily cycles. Disruption of these rhythms through shift work or irregular eating patterns may dysregulate bile acid signaling. Some researchers speculate that time-restricted eating improves metabolic health partly by reinforcing circadian bile acid rhythms.

Avoiding unnecessary antibiotics preserves the bacterial species responsible for bile acid transformation. When antibiotics are necessary, considering probiotic supplementation during and after treatment might help maintain bile acid metabolism, though more research is needed to identify the most effective strains and timing.

The discovery that gut bacteria transform bile acids into hormone-like signaling molecules fundamentally changes how we think about human biology. We're not autonomous organisms running on genetic programming. We're composite beings, and our microbial partners actively shape our metabolism, immunity, and disease risk through their chemical transformations.

This realization carries both promise and complexity. On one hand, the bile acid pathway offers multiple intervention points for treating metabolic disease, inflammation, and potentially cancer. We can develop drugs that mimic or block bile acid signals, engineer bacteria to produce desired bile acid profiles, or use diet and lifestyle to favor beneficial transformations.

On the other hand, the system's complexity makes prediction difficult. Over 50 different bile acid species, two major receptor families with tissue-specific expression, hundreds of bacterial species with varying enzyme activities, and influences from diet, drugs, circadian rhythms, and more create an almost overwhelming number of variables. What works for one person might not work for another, depending on their unique microbiome composition and host genetics.

The research frontier is expanding rapidly. Scientists are using advanced analytical chemistry to identify previously unknown bile acid species. They're mapping which bacterial strains produce which enzymes and under what conditions. They're untangling the signaling cascades downstream of FXR and TGR5 activation. They're testing whether microbiome interventions can improve metabolic outcomes in clinical trials.

What began as a simple story about molecules that help digest fats has become a window into one of biology's most sophisticated regulatory systems. Your gut bacteria are running a hormone factory, churning out signaling molecules that coordinate metabolism across your entire body. Understanding and eventually optimizing this system may be one of the most powerful tools medicine gains in the coming decades.

The liver makes bile acids to digest your lunch. But your gut bacteria have other ideas. They transform those digestive molecules into a chemical language for coordinating the conversation between your microbiome and your metabolism. It's a reminder that human biology is never just human, and that the most important pharmaceutical factories might not be making drugs at all. They might be making us.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

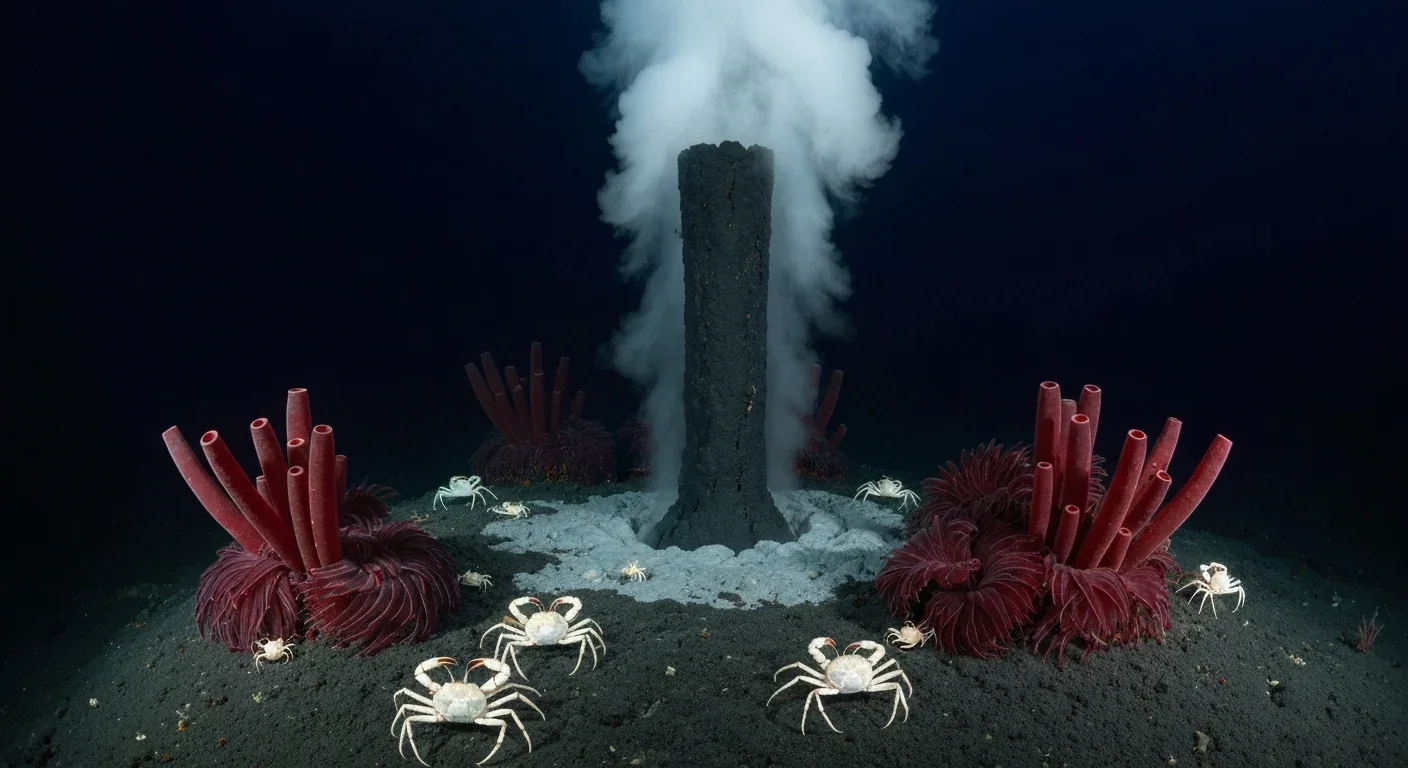

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.