Hidden Blood Pressure Sensors Control Your Stress Response

TL;DR: Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

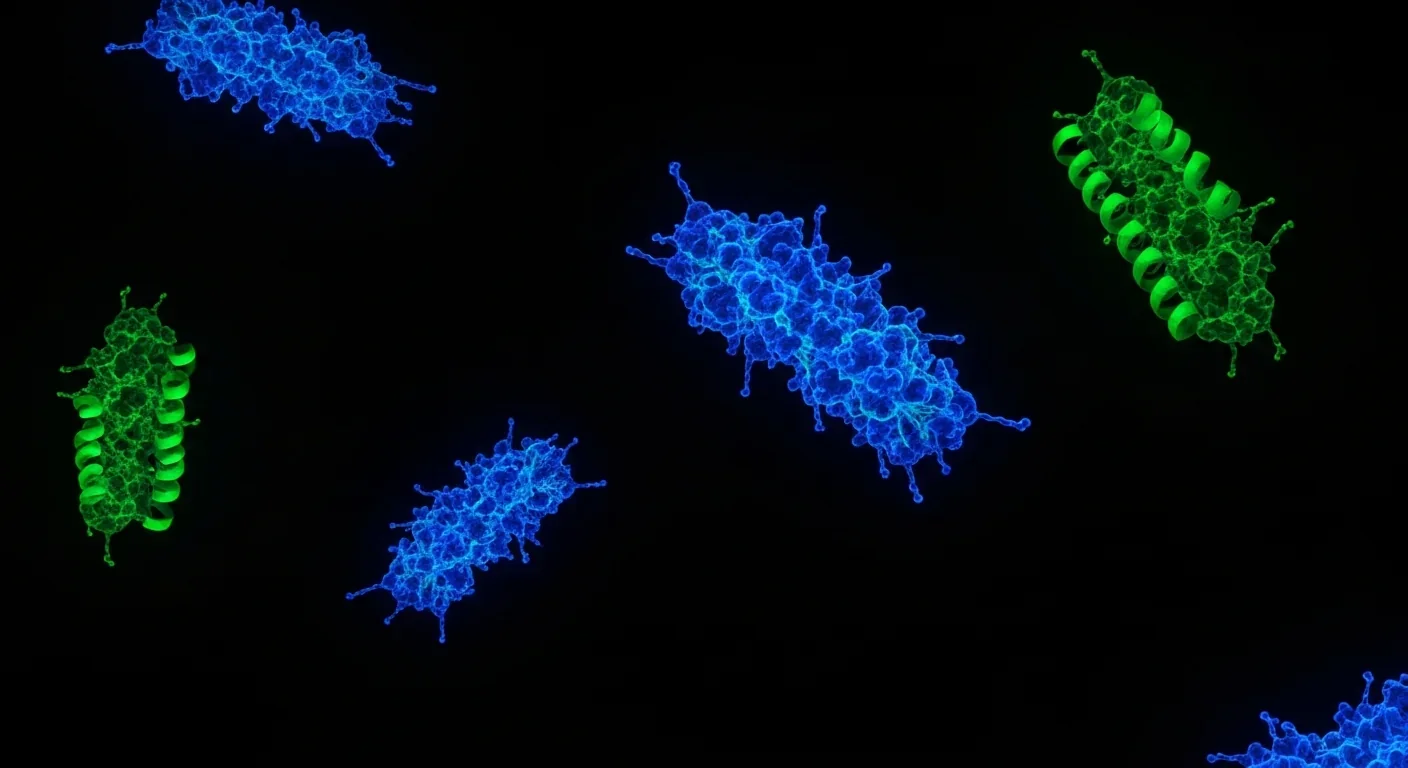

For over half a century, biologists thought they had figured out circadian rhythms. The 24-hour clock that governs when we sleep, when our cells divide, when our hormones surge was all about genes switching on and off in a transcription-translation feedback loop. It was elegant, it was Nobel Prize-winning, and then in 2011, scientists discovered something that shouldn't have been possible. Inside human red blood cells that have no nucleus, no DNA, no genes at all, proteins called peroxiredoxins were keeping perfect time, oscillating in a 24-hour rhythm. This wasn't just an interesting quirk. It was evidence of an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates DNA-based clocks by billions of years and exists in every domain of life from archaea to humans.

Peroxiredoxins are housekeeping proteins, not glamorous clock components. Their day job involves neutralizing reactive oxygen species that damage cells, mopping up hydrogen peroxide and other oxidants like a molecular janitorial service. They're ubiquitous, abundant in virtually every living organism, and for decades nobody thought they had anything to do with circadian biology. The breakthrough came from Akhilesh Reddy's lab at the University of Cambridge, where researchers were studying human red blood cells.

Red blood cells are unusual. To maximize space for oxygen-carrying hemoglobin, they eject their nuclei during maturation, becoming tiny bags of protein and membrane with no genetic material. If circadian clocks required genes cycling on and off, these cells should be clockless zombies, biochemically adrift in time. But when Reddy's team incubated purified red blood cells in darkness at body temperature and sampled them every few hours for days, they found something unexpected. Levels of oxidized peroxiredoxins rose and fell in a clear 24-hour pattern, a rhythm that persisted cycle after cycle without any transcription whatsoever.

The finding was so counterintuitive that it demanded replication. Working with colleagues in Edinburgh and France, the team tested marine algae kept in constant darkness. Same result. A 24-hour peroxiredoxin oxidation rhythm, independent of gene activity. This wasn't a mammalian quirk or a red blood cell oddity. It was something fundamental.

The discovery of 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA challenged the core assumption that biological clocks require genes, revealing an ancient timekeeping system that predates genetic regulation by billions of years.

Before 2011, the dominant explanation for circadian rhythms was the transcription-translation feedback loop, or TTFL model. In its simplest form, clock genes produce clock proteins that eventually shut down their own genes, creating a negative feedback cycle that takes about 24 hours to complete. The discovery in fruit flies earned Jeffrey Hall, Michael Rosbash, and Michael Young the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and similar mechanisms were found in mammals, plants, fungi, and cyanobacteria. It seemed like the universal explanation for biological timekeeping.

The TTFL model had explanatory power. Mutations in clock genes like period disrupted rhythms. Restoring the gene restored the rhythm. The molecular details varied between species but the core logic was the same: genes make proteins, proteins feedback to silence genes, the cycle repeats. It was a complete story, or so it seemed until peroxiredoxins showed up doing their 24-hour dance in cells that couldn't transcribe a single gene.

The implications were immediate and unsettling. If circadian rhythms could exist without transcription or translation, then the TTFL wasn't the whole story. It might not even be the original story. The peroxiredoxin rhythm didn't replace the gene-based clock but it revealed something deeper: a non-transcriptional oscillator that operates in parallel, possibly older, possibly more fundamental than the genetic clockwork biologists had spent decades mapping.

What makes the peroxiredoxin clock so remarkable isn't just that it exists but where it exists. Follow-up studies found the same 24-hour oxidation rhythm in organisms spanning all three domains of life: bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes. It shows up in E. coli, in thermophilic archaea that live in boiling springs, in algae, in fungi, in human cells. This isn't convergent evolution where similar solutions arise independently. This is conservation, a signature of something ancient being passed down across billions of years.

The evolutionary timeline matters. Bacteria and archaea diverged roughly 3.5 billion years ago, long before eukaryotes with their complex gene regulatory networks appeared. If both domains share the peroxiredoxin rhythm, the timekeeping mechanism likely predates their split. That places the origin of this molecular clock in the earliest chapters of cellular life, potentially in the primordial organisms that first had to coordinate their biochemistry with the day-night cycle of the early Earth.

The universality suggests function. Organisms don't maintain a biochemical system across billions of years of evolution unless it's doing something important. The peroxiredoxin rhythm isn't vestigial. It's working, integrated into cellular metabolism, coupling the redox state of the cell to the time of day. In organisms that later evolved transcriptional clocks, the two systems coexist, which raises a provocative question: did DNA-based circadian clocks evolve on top of an older protein-based rhythm, layering genetic regulation onto a metabolic foundation that was already keeping time?

"The finding that circadian rhythms can persist in a cell devoid of DNA and the transcription machinery overturns the long-held belief that genes are essential for a biological clock."

- Research findings from University of Cambridge

The mechanism driving the 24-hour peroxiredoxin cycle is rooted in oxidation chemistry. Peroxiredoxins contain a reactive cysteine residue at their active site. When they encounter hydrogen peroxide or other reactive oxygen species, the cysteine oxidizes to sulfenic acid, neutralizing the threat but altering the protein's structure. Under certain conditions, the sulfenic acid can be further oxidized to sulfinic acid, a modification called hyperoxidation that temporarily inactivates the enzyme.

Here's where it gets interesting. Cells produce reactive oxygen species as a byproduct of metabolism, and metabolic activity fluctuates over the day. During active periods, oxidative stress rises. Peroxiredoxins get oxidized faster than they can be reduced back to their active form. As oxidized peroxiredoxins accumulate, they form high-molecular-weight complexes that can be detected by gel electrophoresis. During rest periods, oxidative pressure drops and specialized enzymes called sulfiredoxins repair the hyperoxidized peroxiredoxins, returning them to their reduced state. The balance between oxidation and reduction creates an oscillation.

But that alone doesn't explain a stable 24-hour rhythm. Oscillations can happen at many timescales depending on reaction rates and substrate availability. What constrains the peroxiredoxin cycle to ~24 hours is still an open question. Some researchers propose that the rhythm is entrained by metabolic cycles that are themselves circadian, creating a feedback loop where peroxiredoxin oxidation reflects the cell's energy state and that state is partly controlled by gene-based clocks. Others suggest intrinsic properties of the oxidation-reduction chemistry, perhaps involving slow conformational changes in protein complexes, generate the periodicity directly.

The details matter because they determine whether the peroxiredoxin rhythm is a true autonomous oscillator or a readout of other circadian processes. Current evidence points to something in between. In systems where transcriptional clocks are intact, peroxiredoxin rhythms track gene-based rhythms. But in red blood cells and algae kept in constant darkness, where transcriptional activity is absent or suppressed, the rhythm persists. That persistence implies the capacity for autonomous oscillation, though in living cells with active genomes, the two clockworks almost certainly communicate.

The peroxiredoxin clock operates through oxidation-reduction chemistry, with proteins cycling between active and hyperoxidized states in response to metabolic rhythms. This creates a biochemical oscillator that doesn't require any genes to function.

If cells have both a transcriptional clock and a non-transcriptional metabolic clock, how do they work together? The relationship is still being mapped, but emerging data suggests coordination rather than competition. Gene-based clocks regulate when certain metabolic enzymes are produced, shaping daily rhythms in energy production, redox balance, and nutrient utilization. Those metabolic shifts in turn influence peroxiredoxin oxidation levels, creating a rhythm in protein modification.

In the other direction, oxidized peroxiredoxins and the reactive oxygen species they regulate can affect gene expression. ROS are signaling molecules, not just cellular damage. They influence transcription factors, modify histones, and alter the activity of epigenetic enzymes. When peroxiredoxin levels oscillate, ROS levels oscillate too, feeding back into the genetic clock. The result is a bidirectional coupling where genes influence metabolism and metabolism influences genes.

This architecture might explain why circadian systems are so robust. If one clock fails, the other provides backup. Mutations that disrupt gene-based rhythms don't eliminate metabolic rhythms, and vice versa. The redundancy buffers against perturbation. It also allows for fine-tuning. Different tissues might rely more heavily on one clock than the other, tailoring their timekeeping to local physiological demands.

The interplay has practical consequences. Studies in mice show that disrupting peroxiredoxin function impairs circadian behavior even when genetic clocks are intact. Oxidative stress management and circadian regulation are intertwined, which means interventions targeting one system will ripple through the other. That's relevant for understanding how jet lag, shift work, and sleep disorders affect cellular health at a molecular level.

Circadian disruption is linked to a growing list of diseases. Shift workers have higher rates of metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers. Night owls forced to wake early show signs of chronic inflammation and insulin resistance. For years, these associations were attributed to the mismatch between genetic clocks and environmental schedules. But if metabolic clocks matter too, if peroxiredoxin rhythms are part of the equation, then circadian health isn't just about when clock genes turn on and off. It's about when cells handle oxidative stress, when mitochondria ramp up energy production, when damage repair systems are active.

Peroxiredoxins are among the most abundant proteins in some cell types, especially red blood cells where PRDX2 can account for significant total protein mass. Their oxidation state is a barometer of cellular redox balance. If that barometer loses its rhythm, the cell loses coordination between its antioxidant defenses and the predictable stresses of day and night. Oxidative damage accumulates at the wrong times. Repair processes activate out of sync. The cumulative effect over years could contribute to aging and age-related disease.

There's growing interest in chronotherapy, the idea that timing medical interventions to align with circadian biology improves outcomes. Chemotherapy administered at optimal times of day causes fewer side effects and works better. Blood pressure medications dosed in the evening reduce cardiovascular events more effectively than morning doses. If peroxiredoxin rhythms influence drug metabolism, immune function, and tissue repair, then chronotherapy needs to consider non-transcriptional clocks too. The timing of oxidative stress, not just gene expression, becomes a therapeutic target.

"The implications of this for health are manifold. We already know that disrupted clocks are associated with metabolic disorders such as diabetes, mental health problems and even cancer."

- ScienceDaily report on peroxiredoxin discovery

Despite a decade of research since the 2011 discovery, major questions remain. The molecular mechanism generating the 24-hour periodicity in peroxiredoxin oxidation is incompletely understood. Is it an intrinsic property of the protein chemistry or does it require external pacing from metabolic cycles? How is the rhythm reset by light and temperature cues, which are classic circadian entrainment signals?

The relationship between transcriptional and non-transcriptional clocks varies across organisms and tissues. In some contexts they seem tightly coupled, in others more independent. What determines the balance? Are there master regulators that coordinate the two systems, or is the coordination emergent from many small feedback loops?

Evolutionary questions abound. If the peroxiredoxin clock is ancient, did it emerge before or after the last universal common ancestor? Could protocells without genomes have had redox-based timekeeping? The conservation across domains suggests deep roots, but fossil biochemistry is hard to trace. Experiments with synthetic minimal cells might provide clues by testing whether simple chemical systems can generate stable 24-hour oscillations.

Clinical translation is just beginning. No drugs currently target peroxiredoxin rhythms specifically. No biomarkers use peroxiredoxin oxidation state to assess circadian health. The diagnostic and therapeutic potential is untapped. Companies developing circadian medicine focus on genetic clocks because the biology is better understood and druggable targets are clearer. As peroxiredoxin research matures, that could change.

The peroxiredoxin story is a reminder that biology is layered. What looks like a complete explanation at one level of analysis turns out to be built on older, deeper mechanisms. Gene-based circadian clocks are sophisticated, tunable, and essential for complex organisms. But they're not the only clocks, and they may not be the first clocks.

Before there were genomes elaborate enough to support transcription-translation feedback loops, there were proteins oscillating in response to redox chemistry. Those oscillations coupled metabolism to time, giving early cells a way to anticipate daily changes in their environment. When genetic regulation evolved, it didn't replace the metabolic clock. It integrated with it, creating a multi-layered timekeeping system that's been refined over billions of years.

We're still learning what that means for how organisms function and how we might intervene when timekeeping goes wrong. The non-transcriptional clock was hidden in plain sight, running in every cell but unrecognized until researchers looked in cells that couldn't do anything else. How many other ancient systems are we missing because we're focused on the newest, most complex layers of regulation?

The next decade of circadian research will have to grapple with this complexity. Clock genes remain important, but they're not the whole clock. Peroxiredoxins are part of the machinery, and so is the entire metabolic network that produces and consumes reactive oxygen species. Time isn't just written in our genes. It's written in the rhythm of our chemistry, in the oscillations of proteins that predate DNA-based life and persist in every cell we have.

What started as a puzzling observation in red blood cells is rewriting the history of biological timekeeping. The ancient protein clock that ticks without DNA is teaching us that life has been keeping time longer than we thought, in ways we're only beginning to understand.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

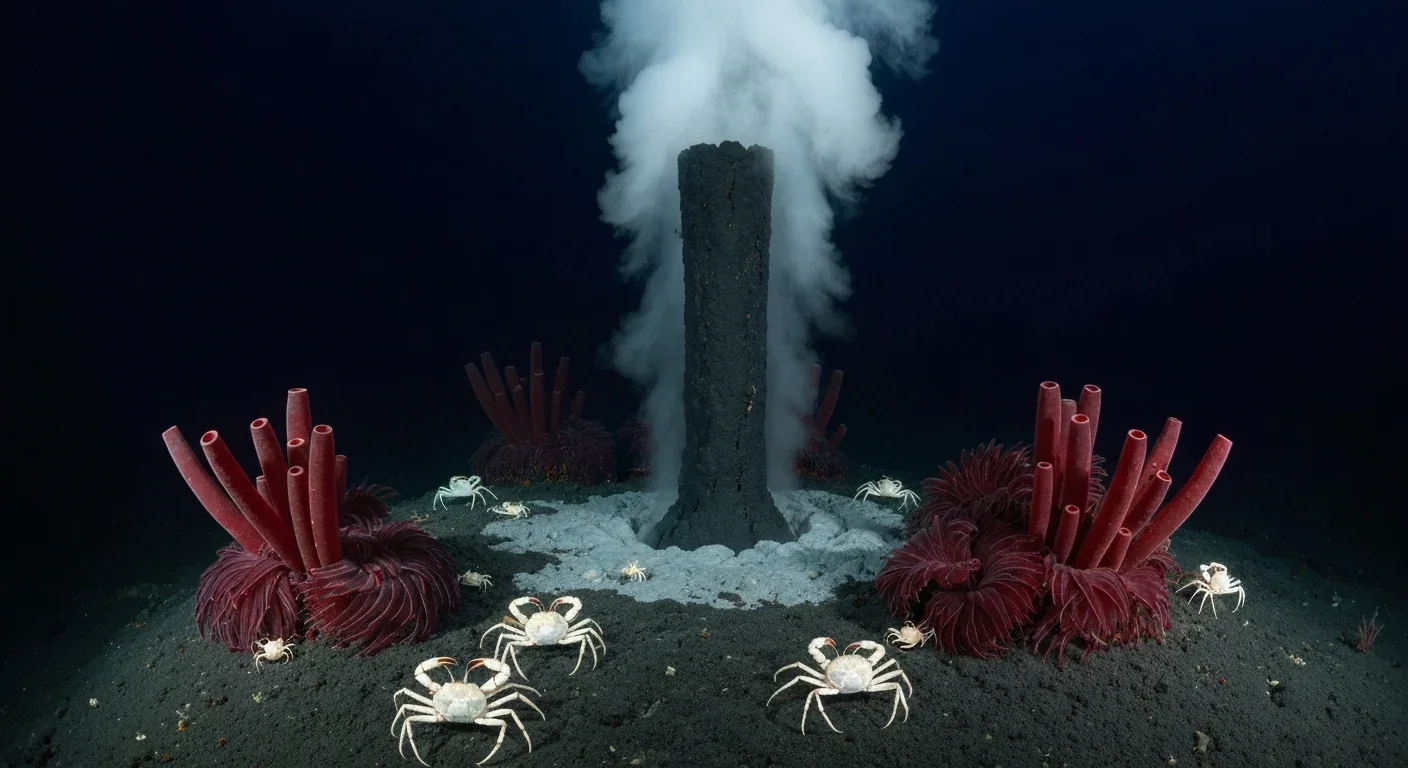

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

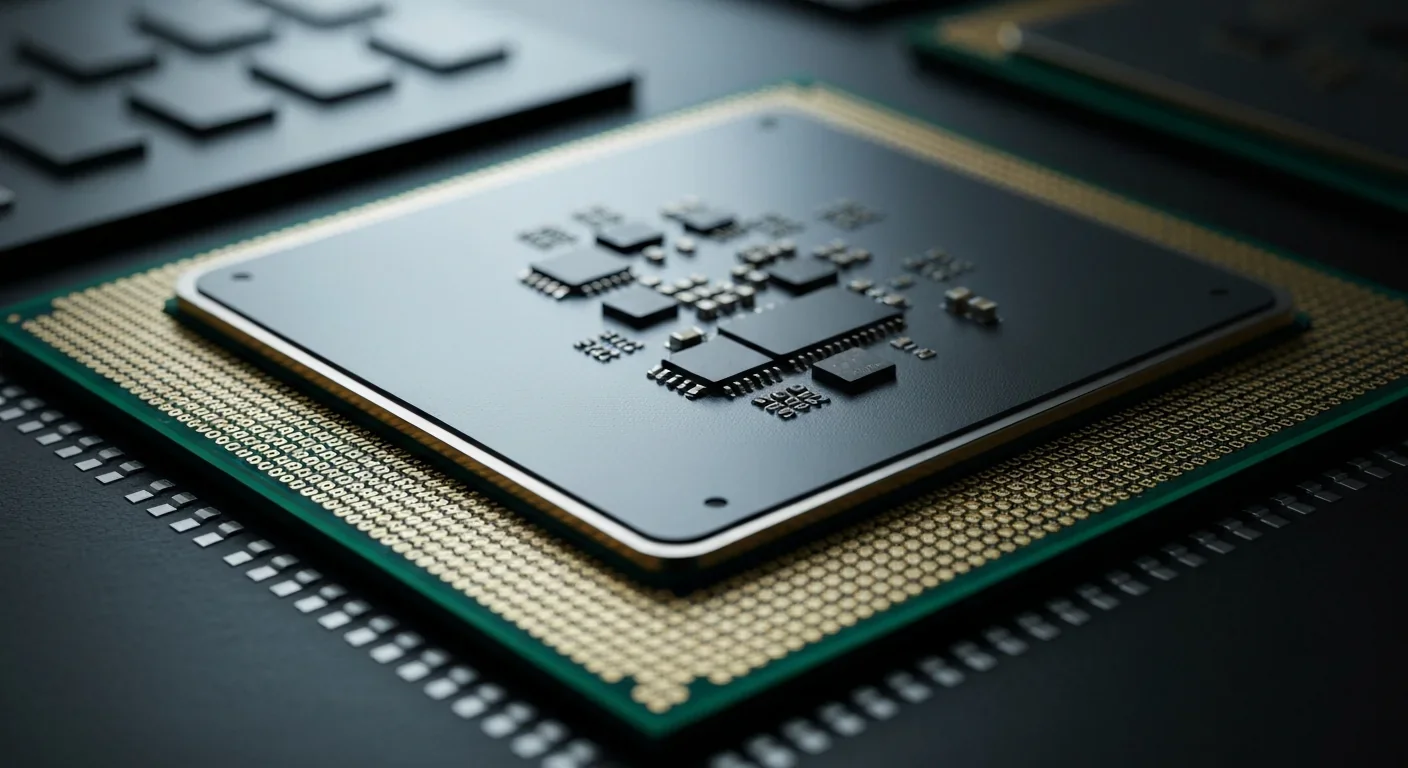

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.