The Ancient Protein Clock That Ticks Without DNA

TL;DR: Lipofuscin, the 'age pigment' accumulating in cells, may predict biological aging more accurately than chronological age. This golden-brown cellular waste forms when lysosomes can't break down damaged proteins and fats, with rates varying dramatically between individuals based on genetics and lifestyle. Scientists are developing measurement techniques and therapeutic strategies to track and reduce lipofuscin, potentially revolutionizing how we assess health and develop anti-aging interventions.

Your body keeps a secret tally of how fast you're aging, and it's written in a golden-brown pigment accumulating inside your cells right now. Lipofuscin - often called the "age pigment" - builds up in nearly every tissue as you live, but here's what makes it fascinating: two people born on the same day can have wildly different amounts. This discrepancy isn't random noise. It's a biological signature that might predict your healthspan more accurately than the number of candles on your birthday cake.

While chronological age simply counts trips around the sun, lipofuscin measures something more fundamental: how efficiently your cells handle the molecular damage of staying alive. Scientists are now developing ways to measure this cellular trash as a biomarker, potentially transforming how we assess biological age and predict disease risk decades before symptoms appear.

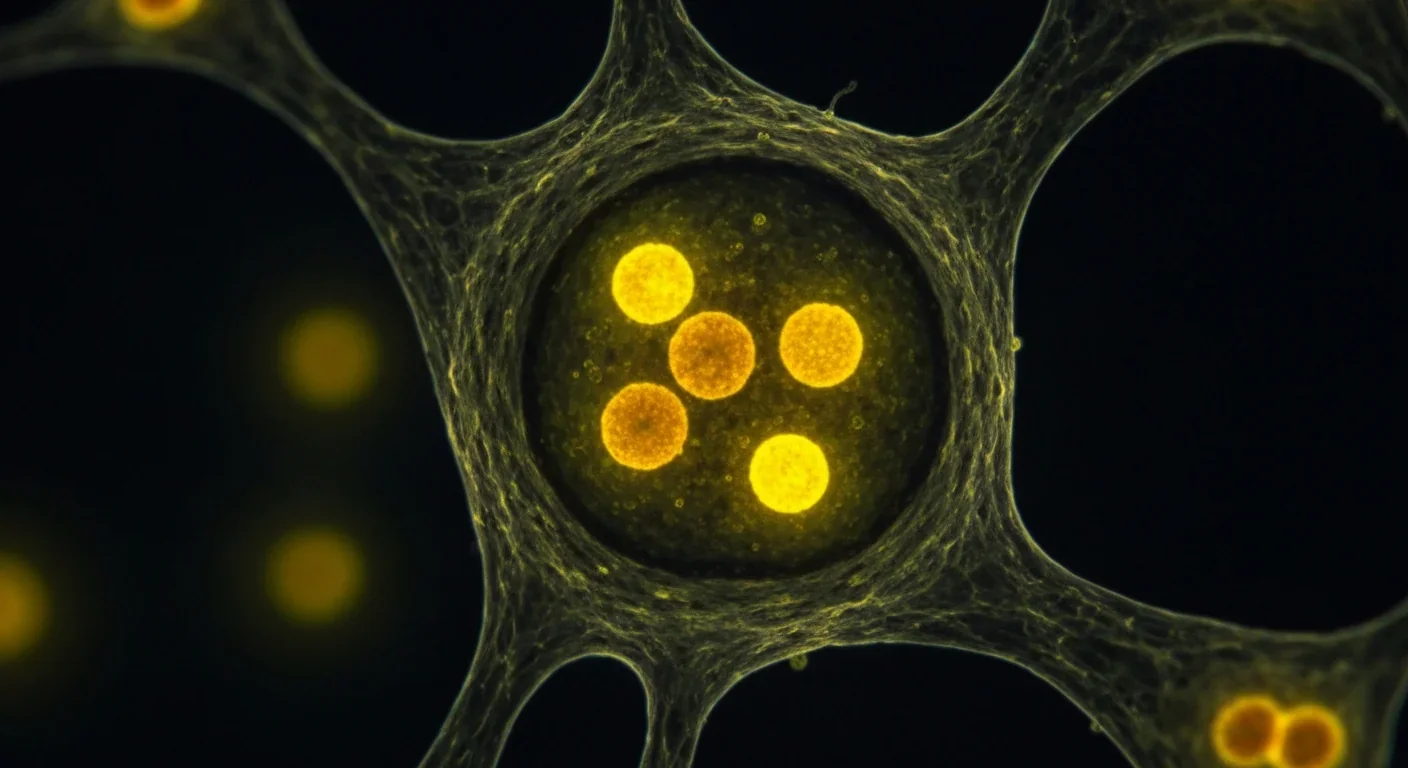

Lipofuscin forms when your cells can't completely digest damaged proteins and oxidized fats. Think of it as the ash that remains after your cellular recycling system - primarily structures called lysosomes - tries to break down worn-out components. Unlike ash, though, this residue is fluorescent, making it relatively easy to spot under specialized microscopes.

The pigment consists mainly of cross-linked proteins and oxidized lipids that form complex aggregates resistant to enzymatic breakdown. Once formed, lipofuscin is essentially permanent - your cells can't get rid of it. Instead, these golden granules accumulate in the cytoplasm, gradually filling up space that could otherwise support cellular function.

What makes lipofuscin particularly intriguing is where it accumulates. Post-mitotic cells - neurons, cardiac muscle cells, and retinal cells that can't divide and replace themselves - show the heaviest accumulation. In the brain and heart, lipofuscin can occupy up to 30% of cellular volume in advanced age. This isn't merely cosmetic. The pigment displaces organelles and interferes with cellular metabolism, potentially contributing to the functional decline we associate with aging.

In aged neurons and heart cells, lipofuscin can fill up to 30% of cellular volume, physically crowding out functional machinery and contributing to age-related decline.

Understanding how lipofuscin forms requires looking at your cells' waste management system. Lysosomes act as cellular stomachs, using powerful enzymes to break down damaged components into reusable building blocks. This process, called autophagy, normally works efficiently - but it has an Achilles heel.

When proteins and fats undergo oxidative damage from normal metabolism or environmental stressors, they can become chemically modified in ways that make them resistant to enzymatic digestion. Free radicals, those reactive molecules produced during energy generation in mitochondria, are major culprits. They attack cellular components, creating cross-linked structures that enzymes can't cleave.

Here's where the problem compounds: as we age, lysosomal function itself declines. The pH inside lysosomes tends to increase with age, making their digestive enzymes less effective. Research from 2025 shows that lysosomal acidification failure drives aging in stem cells, creating a vicious cycle. Weakened lysosomes can't fully break down damaged material, so lipofuscin accumulates. The growing lipofuscin burden then further impairs lysosomal function, accelerating the accumulation.

Individual variation in lipofuscin accumulation stems from multiple factors. Genetic differences in antioxidant systems affect how much oxidative damage occurs in the first place. The FOXO3 gene, strongly associated with human longevity, regulates both antioxidant production and autophagy efficiency. People with beneficial FOXO3 variants may accumulate lipofuscin more slowly, helping explain their extended healthspans.

Environmental exposures also matter. Smoking, UV radiation, poor diet, and chronic inflammation all increase oxidative stress, accelerating lipofuscin formation. This is why biological age can diverge so dramatically from chronological age - your lifestyle and genetics determine how fast your cellular trash piles up.

For lipofuscin to serve as a practical biomarker, we need reliable ways to measure it. Fortunately, the pigment's natural autofluorescence provides a detection method. When excited by blue light (around 340-490 nm), lipofuscin emits a distinctive yellow-brown fluorescence (peak around 540-640 nm).

Researchers have developed several approaches to exploit this property. Fluorescence lifetime imaging ophthalmoscopy can measure lipofuscin in the retina non-invasively, providing a window into cellular aging that doesn't require biopsies. Since retinal pigment epithelium accumulates lipofuscin predictably with age, and retinal health correlates with neurological function, this technique might detect early signs of age-related neurodegeneration.

For research purposes, scientists can quantify lipofuscin in tissue samples using specialized autofluorescence microscopy. By measuring the intensity and distribution of fluorescent granules, they can assess the aging status of specific tissues. Flow cytometry offers another option, sorting cells based on their autofluorescence to identify heavily lipofuscin-laden populations.

The challenge is translating these laboratory techniques into clinical diagnostics. Retinal imaging shows promise for accessible screening, but lipofuscin burden in the eye may not perfectly reflect accumulation in other organs. Researchers are working on blood-based biomarkers - potentially measuring circulating markers of lysosomal dysfunction or oxidative damage that correlate with tissue lipofuscin levels.

A 2025 paper on advancing single-cell detection of senescent cells highlights how autofluorescence can identify aged cells in mixed populations. This capability could enable personalized aging assessments, revealing whether your immune cells, for instance, show accelerated or decelerated biological aging compared to population norms.

"Lipofuscin autofluorescence provides a non-invasive window into cellular aging, potentially detecting neurodegeneration years before clinical symptoms emerge."

- Advanced ophthalmology research, 2025

The critical question is whether lipofuscin merely marks cellular aging or actively drives it. The distinction matters enormously for therapeutic development. If lipofuscin is just a passenger - a harmless consequence of aging - removing it won't help. If it's a driver, clearing lipofuscin could rejuvenate aged cells.

Evidence suggests lipofuscin sits somewhere between these extremes. It's not entirely inert. Studies show that lipofuscin accumulation impairs cellular function through multiple mechanisms. The granules physically crowd the cytoplasm, reducing space for functional organelles. They may sequester iron and other metals, contributing to oxidative stress. Lipofuscin-loaded lysosomes show reduced capacity to degrade new cargo, compromising the cell's ability to maintain quality control.

In age-related macular degeneration (AMD), lipofuscin in retinal pigment epithelium plays a particularly sinister role. The bisretinoid compounds in retinal lipofuscin are photoreactive, generating reactive oxygen species when exposed to light. This creates a feedback loop: light-induced damage produces more lipofuscin, which amplifies light-induced damage, ultimately killing retinal cells and causing vision loss.

Neurological diseases provide additional evidence. In Alzheimer's disease, neurons heavily laden with lipofuscin show greater dysfunction. The pigment interferes with protein homeostasis and may contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction, the energetic crisis that characterizes many neurodegenerative conditions.

Yet lipofuscin is probably not the primary driver of aging in most tissues. Rather, it reflects upstream problems - chronic oxidative stress, declining autophagy, and lysosomal dysfunction - that have broader consequences beyond just pigment accumulation. This makes lipofuscin a useful biomarker of these more fundamental aging processes, even if it's not the main culprit.

If lipofuscin contributes to age-related dysfunction, removing it could restore cellular health. Several research teams are tackling this challenge, though it's proven difficult.

One promising approach uses beta-cyclodextrins, cyclic sugar molecules that can bind and promote degradation of lipofuscin bisretinoids. In cultured retinal cells, beta-cyclodextrin treatment reduced autofluorescent lipofuscin by 35%. The mechanism appears to involve stimulating lysosomal degradation pathways rather than just expelling the pigment. Since beta-cyclodextrins are already in human trials for Niemann-Pick disease, a cholesterol storage disorder, they could potentially be repurposed for lipofuscin-related conditions like AMD.

Another strategy focuses on enhancing autophagy and lysosomal function. Compounds that boost autophagy - like certain natural products acting through insulin/IGF-1 signaling - can slow lipofuscin accumulation in animal models. In C. elegans worms, treatments that extend lifespan consistently reduce lipofuscin burden, suggesting the two are mechanistically linked.

Restoring lysosomal pH represents another intervention point. If age-related lysosomal alkalinization impairs digestion of cellular components, acidifying lysosomes might prevent lipofuscin formation. Small molecules that enhance lysosomal acidification are under investigation.

Some researchers propose a more radical approach: treating lipofuscin-laden cells as senescent and targeting them for elimination. Senolytic drugs, which selectively kill senescent cells, might also clear heavily lipofuscin-loaded cells if the two populations overlap significantly. Early evidence suggests autofluorescence could identify senescent cells for targeted elimination.

Beta-cyclodextrin treatment reduced lipofuscin by 35% in retinal cells, and these compounds are already in human trials for other conditions - suggesting rapid translation to anti-aging therapies.

The recognition of lipofuscin as a biological age biomarker opens several promising directions. First, it provides an objective measure of aging at the cellular level, complementing DNA methylation clocks and other biomarkers. A comprehensive aging assessment might combine multiple markers - epigenetic, proteomic, and pigment-based - to generate a complete biological age profile.

Second, lipofuscin measurement could enable personalized health monitoring. Imagine getting your retinal lipofuscin measured during a routine eye exam, providing an early warning if your biological age is outpacing your chronological age. This could motivate lifestyle changes or medical interventions before overt disease develops.

Third, lipofuscin offers a mechanistic link between aging and specific diseases. The relationship between lipofuscin and neurodegeneration suggests that therapies targeting pigment accumulation might prevent or delay conditions like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Similarly, clearing retinal lipofuscin could protect against AMD, one of the leading causes of blindness in developed countries.

From a research perspective, lipofuscin provides a quantifiable endpoint for testing anti-aging interventions. If a drug or dietary intervention claims to slow aging, does it reduce lipofuscin accumulation in animal models? In humans? This concrete measure could help separate genuine anti-aging therapies from snake oil.

The field also highlights the importance of maintaining cellular quality control systems. Much of aging may stem not from irreparable damage to DNA or proteins, but from the gradual failure of housekeeping mechanisms that normally clear damaged components. Supporting autophagy and lysosomal function - through diet, exercise, or pharmaceutical interventions - might be more important than we realized.

Lipofuscin research is part of a broader transformation in how we think about aging. Instead of viewing it as a uniform, inevitable decline, we're recognizing aging as a multifaceted process with distinct hallmarks - genomic instability, epigenetic alterations, proteostasis loss, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, and more.

Different tissues and even different cells within the same tissue age at different rates. Your brain might be biologically 40 while your heart is 60, based on the molecular and cellular changes each has accumulated. Lipofuscin is one window into this tissue-specific aging, particularly relevant for post-mitotic cells that can't dilute their pigment burden through division.

This heterogeneity explains why chronological age is such an imperfect predictor of health outcomes. We all know people who seem much younger or older than their years. Biological age biomarkers like lipofuscin help quantify these differences, potentially identifying who needs more aggressive preventive care and who's doing fine.

The ultimate goal is developing interventions that target the root causes of biological aging rather than just treating age-related diseases one by one. If we can slow lipofuscin accumulation by supporting lysosomal function and reducing oxidative stress, we might simultaneously reduce risk for neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disease, and vision loss. This represents a fundamentally different approach to medicine - maintaining the robustness of cellular housekeeping systems rather than waiting for them to fail.

"The goal isn't just to live longer, but to extend the period of healthy, vibrant life by maintaining the cellular quality control systems that keep our tissues functioning optimally."

- Longevity research perspective

While lipofuscin-targeted therapies remain experimental, the mechanisms underlying its accumulation suggest practical steps. Reducing oxidative stress through a diet rich in antioxidants - particularly colorful vegetables and fruits - may slow pigment formation. Regular exercise enhances autophagy, helping cells clear damaged components before they become lipofuscin.

Avoiding pro-oxidant exposures matters too. Smoking dramatically accelerates lipofuscin accumulation. Excessive alcohol consumption impairs lysosomal function. Managing chronic inflammation through good sleep, stress reduction, and treatment of inflammatory conditions addresses another accelerator of cellular aging.

Intermittent fasting and caloric restriction, the most reliable interventions for extending lifespan in animals, both enhance autophagy and reduce lipofuscin accumulation. You don't need to starve yourself - even time-restricted eating (limiting food intake to an 8-10 hour window) activates some of these beneficial pathways.

As measurement technologies improve, tracking your own lipofuscin burden may become feasible. Retinal imaging clinics are beginning to offer autofluorescence measurements. While interpretation standards are still developing, having a baseline could prove valuable as the science advances.

The next decade will likely bring major advances in understanding and manipulating lipofuscin. Clinical trials of beta-cyclodextrins for AMD will reveal whether directly targeting the pigment improves outcomes. Large-scale studies correlating retinal lipofuscin with health trajectories will establish whether it predicts disease and mortality independently of other risk factors.

We might see lipofuscin measurement incorporated into comprehensive biological age assessments, sitting alongside epigenetic clocks, inflammatory markers, and metabolic parameters. Insurance companies and healthcare systems could use these metrics to stratify risk and target preventive interventions to those who would benefit most.

More fundamentally, lipofuscin research is teaching us that aging isn't a single, monolithic process. It's a collection of distinct cellular and molecular changes, many of which can be measured, modulated, and potentially reversed. Each biomarker - whether lipofuscin, senescent cells, or DNA methylation patterns - reveals a different facet of the aging process.

This multiplicity offers hope. We don't need to solve aging all at once. Targeting even one mechanism, like lipofuscin accumulation, might extend healthspan and compress morbidity - the period of late-life disability. Combined interventions addressing multiple aging hallmarks simultaneously could be transformative.

The age pigment accumulating silently in your cells isn't just a curiosity. It's a biological clock, a window into cellular aging, and potentially a therapeutic target. As we develop better ways to read this clock and, eventually, turn it back, we move closer to a future where your chronological age says less and less about your health, vitality, and remaining years. The golden-brown granules in your neurons and heart cells might just hold the key to making 60 the new 40 - not through wishful thinking, but through precise, mechanism-based interventions that give your cells the tools to keep their own houses clean.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

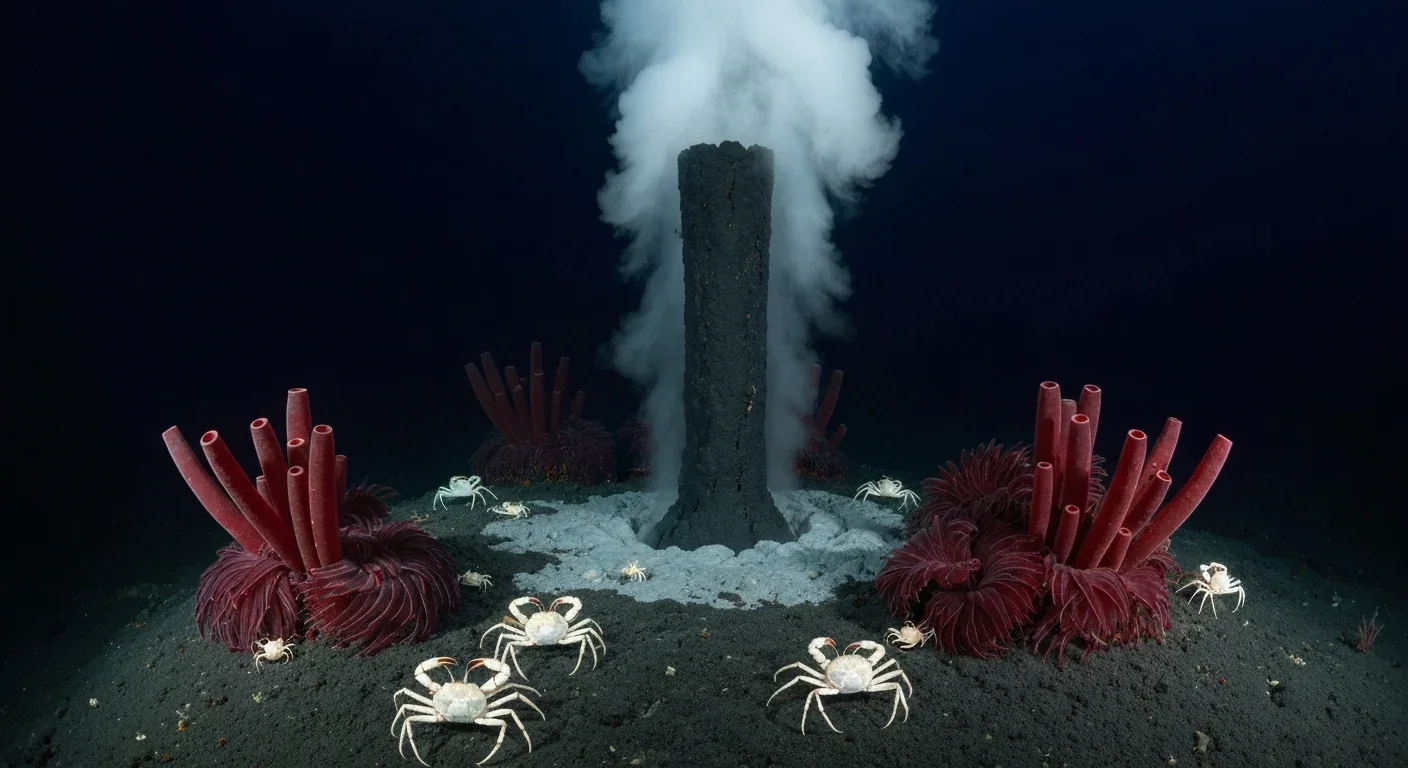

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

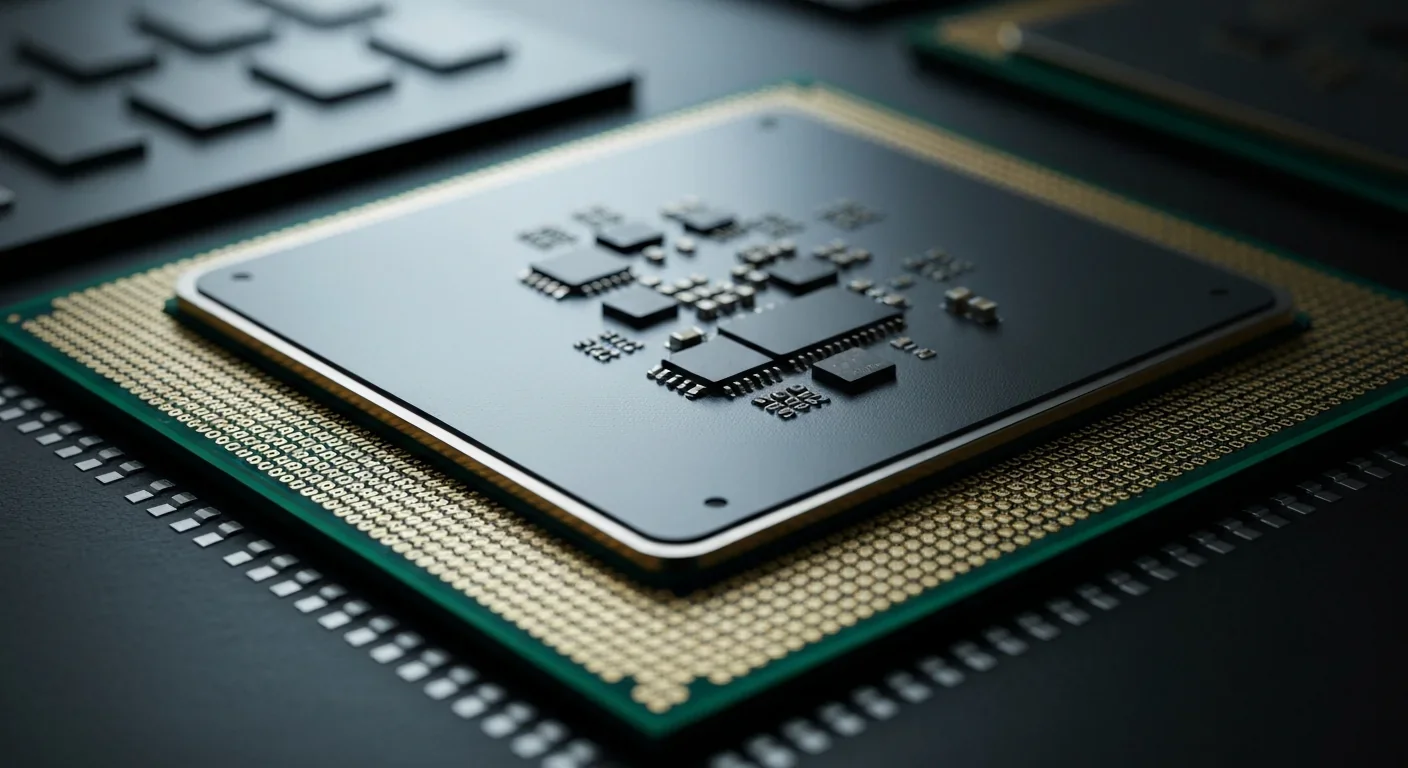

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.