Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: Between 30-50% of new buildings cause sick building syndrome through VOC off-gassing from common construction materials. This investigation reveals which products are the worst offenders, how to detect VOCs, and practical solutions including low-VOC alternatives now available at mainstream retailers.

A quiet transformation is happening in how we understand indoor spaces. After decades of sealing buildings tighter for energy efficiency, we're discovering an uncomfortable truth: the very materials we use to construct modern buildings are slowly poisoning the people inside them. Between 30 and 50 percent of new or refurbished buildings now cause sick building syndrome, a constellation of symptoms that mysteriously appear when you enter certain structures and vanish when you leave.

The culprit? Invisible chemicals called volatile organic compounds that off-gas from everyday construction materials, creating indoor air that's often more polluted than the smog-choked streets outside.

Volatile organic compounds are carbon-based chemicals that evaporate at room temperature, transforming from solid or liquid form into invisible gases that you breathe with every inhale. They're everywhere in modern construction: the adhesive bonding your particle board, the paint on your walls, the stain on your hardwood floors, even the carpet beneath your feet.

The EPA recognizes thousands of different VOCs, but some of the most common offenders include formaldehyde, benzene, toluene, and xylene. These aren't obscure industrial chemicals locked away in laboratories. They're in the materials surrounding you right now.

That new-house smell people love? That's actually the scent of toxic chemicals off-gassing into your lungs.

What makes VOCs particularly insidious is their invisibility. You can't see them, and by the time you smell them, you've already been exposed. Some VOCs have no odor at all, silently accumulating in poorly ventilated spaces until they reach concentrations that trigger health effects.

The World Health Organization officially recognized sick building syndrome back in 1982, but it took decades for the construction industry to take the problem seriously. The syndrome manifests through a frustrating pattern: people feel fine at home, develop symptoms at work, and recover once they leave the building. It's not psychosomatic, and it's not just people being sensitive.

Research shows that VOC exposure triggers a cascade of physiological responses. When you breathe these compounds, they interact with the mucous membranes in your eyes, nose, and throat, causing immediate irritation. Some VOCs cross the blood-brain barrier, leading to headaches, dizziness, and cognitive impairment.

A 2015 study in Iranian office buildings found direct correlations between indoor pollutant levels and symptom severity. As carbon dioxide and VOC concentrations climbed, so did reports of nausea, headaches, nasal irritation, and throat dryness.

What's particularly troubling is that symptoms often improve or disappear when people leave the affected building. This temporary relief masks the cumulative damage happening over months or years of exposure. You're not imagining things when your office gives you headaches. Your body is literally responding to a toxic environment.

Not all building materials are created equal when it comes to VOC emissions. Some products off-gas heavily for weeks or months after installation, while others continue releasing chemicals for years.

Paint and Coatings: Traditional paints are among the worst offenders, releasing a cocktail of VOCs as they dry. The problem doesn't stop once the paint feels dry to the touch. Studies using advanced analytical chemistry methods have documented that VOC emissions from decorative materials continue for months, with emission rates varying dramatically based on temperature and humidity.

Adhesives and Sealants: The glues binding your plywood, particle board, and laminate flooring often contain formaldehyde-based resins. These materials are particularly problematic because they're hidden inside walls and under surfaces, continuously off-gassing where you can't see or easily remediate them.

Carpeting: Wall-to-wall carpet systems involve multiple VOC sources, including the carpet backing, padding, and installation adhesives. Even low-VOC carpets from major retailers can emit concerning levels of chemicals during the first few months after installation.

Insulation Materials: Rigid foam insulation and spray foam products often contain isocyanates and other reactive chemicals that can off-gas for extended periods. These materials are typically sealed inside walls, creating a slow-release capsule of chemicals that seeps into your living space through tiny gaps and cracks.

Vinyl Flooring: Luxury vinyl planks and vinyl composition tile release phthalates and other plasticizers as they age. Unlike some products that off-gas heavily at first then taper off, vinyl products can continue emitting chemicals throughout their entire lifespan.

Research published in MDPI's Buildings journal found that even moderate temperature increases dramatically accelerate VOC emissions from modern building materials. This means your building's indoor air quality can deteriorate significantly during summer months or in spaces with poor climate control.

The health effects of VOC exposure exist on a spectrum, from minor irritation to serious long-term conditions. Understanding this range helps explain why some people barely notice building-related symptoms while others become severely debilitated.

Acute Effects appear within hours or days of exposure and typically resolve when you leave the contaminated environment. These include eye irritation, headaches, dizziness, nausea, and fatigue. You might experience difficulty concentrating, often described as "brain fog," or notice your eyes watering and nose running despite having no cold or allergies.

"Between 30 and 50 percent of new or refurbished buildings can cause some form of Sick Building Syndrome."

- Health and Safety Executive (HSE) estimates

Subacute Effects develop after weeks or months of repeated exposure. Persistent respiratory irritation can evolve into chronic cough or worsen existing asthma. Some people develop chemical sensitivity, where even low-level exposures trigger disproportionate reactions.

Chronic Effects emerge from years of exposure and can include serious respiratory disease, liver and kidney damage, and neurological impairment. The EPA classifies several common construction VOCs as probable or known carcinogens, with formaldehyde being the most concerning.

The risk isn't distributed equally across all populations. Children are particularly vulnerable because they breathe more air relative to their body weight and their developing systems are more susceptible to chemical damage. Pregnant women face additional concerns, as some VOCs can cross the placental barrier and potentially affect fetal development.

An extensive analysis published in MDPI's Biosensors journal documented the complex interplay between VOC exposure, sampling methods, and health risk assessment. The researchers emphasized that current exposure limits might not adequately protect sensitive populations, particularly given the synergistic effects when multiple VOCs are present simultaneously.

The regulatory landscape for VOC emissions varies dramatically depending on where you live and what type of building you're constructing. In the United States, the EPA has established guidelines but lacks comprehensive mandatory standards for most building materials.

The Toxic Substances Control Act gives the EPA authority to regulate certain chemicals, and the agency has prioritized several VOCs for risk evaluation. However, the process is slow, and many problematic chemicals remain largely unregulated in consumer products.

ASHRAE Standard 62.1 provides ventilation requirements for acceptable indoor air quality, recommending 5 to 10 cubic feet per minute of fresh air per occupant. The standard also calls for a minimum of 8.4 air exchanges per 24-hour period in residential settings.

California's formaldehyde regulations are among the strictest in the nation, establishing emission limits for composite wood products that have effectively become de facto national standards since manufacturers don't want to produce different products for different states.

Understanding environmental regulations in construction remains challenging for builders and developers because requirements vary between federal, state, and local jurisdictions. Some municipalities have adopted green building codes that mandate low-VOC materials, while others have no specific requirements beyond basic safety standards.

Europe generally takes a more precautionary approach, with several countries implementing comprehensive VOC labeling systems that inform consumers about emission levels. The European Union's REACH regulation provides a framework for managing chemical risks that's more proactive than U.S. approaches.

The good news is that low-VOC construction products have improved dramatically over the past decade. What were once niche products used only in specialty green buildings are now widely available at mainstream retailers and competitive in price with conventional alternatives.

Major manufacturers now offer zero-VOC paints that contain fewer than 5 grams per liter of VOCs, compared to 50-150 g/L for conventional paints.

Paint and Coatings: Major manufacturers now offer extensive lines of zero-VOC and low-VOC paints that perform comparably to traditional formulations. Some companies have developed truly zero-emission formulas using water-based chemistries that eliminate organic solvents entirely.

Adhesives: Water-based and solvent-free adhesives have replaced traditional formulations in many applications. For wood products, manufacturers increasingly use polyurethane-based binders that emit fewer VOCs than formaldehyde-urea-formaldehyde resins.

Flooring: Healthy building products include a growing range of low-emission flooring options. Natural linoleum, cork, bamboo, and hardwood finished with water-based sealers all emit significantly fewer VOCs than vinyl products or carpeting with synthetic backing.

When selecting low-VOC materials, certification matters. Look for products tested according to standardized protocols like ASTM D5116 or ISO 16000, which measure emissions in controlled chamber environments. Third-party certifications from organizations like Greenguard provide independent verification of manufacturer claims.

You can't manage what you can't measure, and detecting VOCs requires specialized equipment that can identify and quantify compounds at parts-per-billion concentrations.

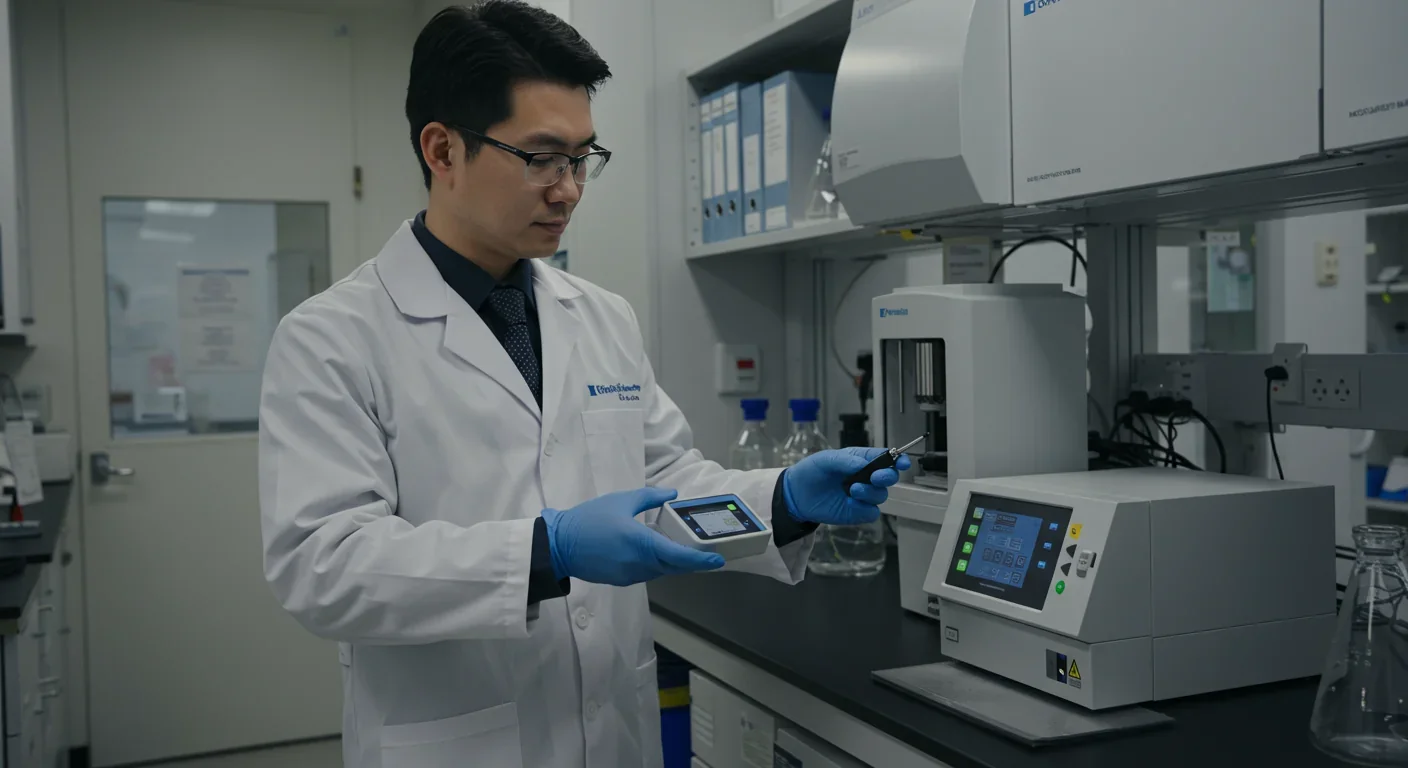

Professional VOC meters use photoionization detectors or electrochemical sensors to measure total volatile organic compound levels in real-time. These devices provide immediate feedback about indoor air quality, allowing you to identify problem areas and verify that remediation efforts are working.

For detailed analysis, laboratory testing services collect air samples using specialized canisters or sorbent tubes that capture VOCs for later analysis via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Testing typically costs $200-400 per sample but delivers far more actionable data than consumer-grade screening tools.

Consumer-level air quality monitors have become increasingly sophisticated and affordable. Devices costing $100-300 can now detect VOCs along with particulate matter, carbon dioxide, and other indoor pollutants. While these aren't as accurate as professional equipment, they're sufficient for identifying potential problems that warrant further investigation.

The timing of testing matters significantly. VOC emissions are highest immediately after material installation and decrease over time following a logarithmic decay curve. A comprehensive assessment typically includes baseline testing before occupancy, follow-up testing at 30 days, and periodic monitoring over the first year.

Solving VOC problems in existing buildings requires a multi-layered approach addressing sources, ventilation, and occupant behavior.

Source Control: This is always the first priority. Identifying and removing high-emitting materials provides the most effective long-term solution. Sometimes this is straightforward, like replacing a particularly toxic carpet or repainting with low-VOC products.

When removal isn't feasible, encapsulation can work. Specialized sealants create vapor barriers that trap VOCs inside materials, preventing them from entering occupied spaces.

Ventilation Enhancement: Since you spend roughly 90% of your time indoors, and indoor air often contains 2-5 times more pollutants than outdoor air, dramatically increasing ventilation can dilute VOC concentrations to safer levels.

"Doubling ventilation rates increased worker productivity by 1.7%, a benefit that far exceeds the incremental energy costs."

- Research on ventilation and productivity

Mechanical ventilation systems with energy recovery allow you to bring in fresh outdoor air while minimizing heating and cooling costs. These systems exchange heat and moisture between outgoing and incoming air streams, recovering up to 80% of the energy that would otherwise be lost.

Air Cleaning: Advanced air purification systems can remove VOCs from indoor air, though their effectiveness varies by technology and specific compounds. Activated carbon filters absorb many VOCs through adsorption, though they become saturated over time and require replacement.

Photocatalytic oxidation systems use ultraviolet light and titanium dioxide catalysts to decompose VOCs into carbon dioxide and water. These work continuously without filter replacement, but their effectiveness depends heavily on air flow patterns and contact time.

Material Selection: Prevention beats remediation every time. Specifying low-VOC products from the design phase costs no more than using conventional materials but eliminates problems before they start.

We're at an inflection point in how society thinks about indoor air quality. For decades, building codes prioritized structural safety and energy efficiency while ignoring the chemical composition of indoor air. That's changing, driven by mounting evidence that poor indoor air quality imposes substantial health and economic costs.

The next generation of building materials will likely integrate active air purification capabilities. Photocatalytic coatings, materials embedded with activated carbon, and surfaces that release beneficial compounds to neutralize pollutants are all moving from laboratory research to commercial products.

Smart building systems will continuously monitor indoor air quality and automatically adjust ventilation, filtration, and even window positions to maintain optimal conditions. Machine learning algorithms will predict when specific spaces need intervention based on occupancy patterns, weather conditions, and historical data.

Within the next decade, constructing buildings with high-VOC materials will seem as outdated as installing asbestos insulation or lead pipes.

Perhaps most importantly, the market is shifting. Prospective tenants and homebuyers increasingly ask about indoor air quality before signing leases or closing purchases. Some commercial landlords now tout their buildings' superior air quality as a competitive advantage for attracting tenants.

The sick building syndrome epidemic didn't happen because manufacturers or builders were deliberately creating toxic environments. It resulted from optimizing for the wrong variables, prioritizing initial costs and energy efficiency while ignoring long-term health impacts.

As our understanding of VOC toxicity deepens and alternatives become readily available, there's simply no justification for continuing to construct buildings that make people sick. The question isn't whether the construction industry will transition to healthier materials, but how quickly we can accelerate that transition to protect the billions of people spending their lives inside buildings that are slowly poisoning them.

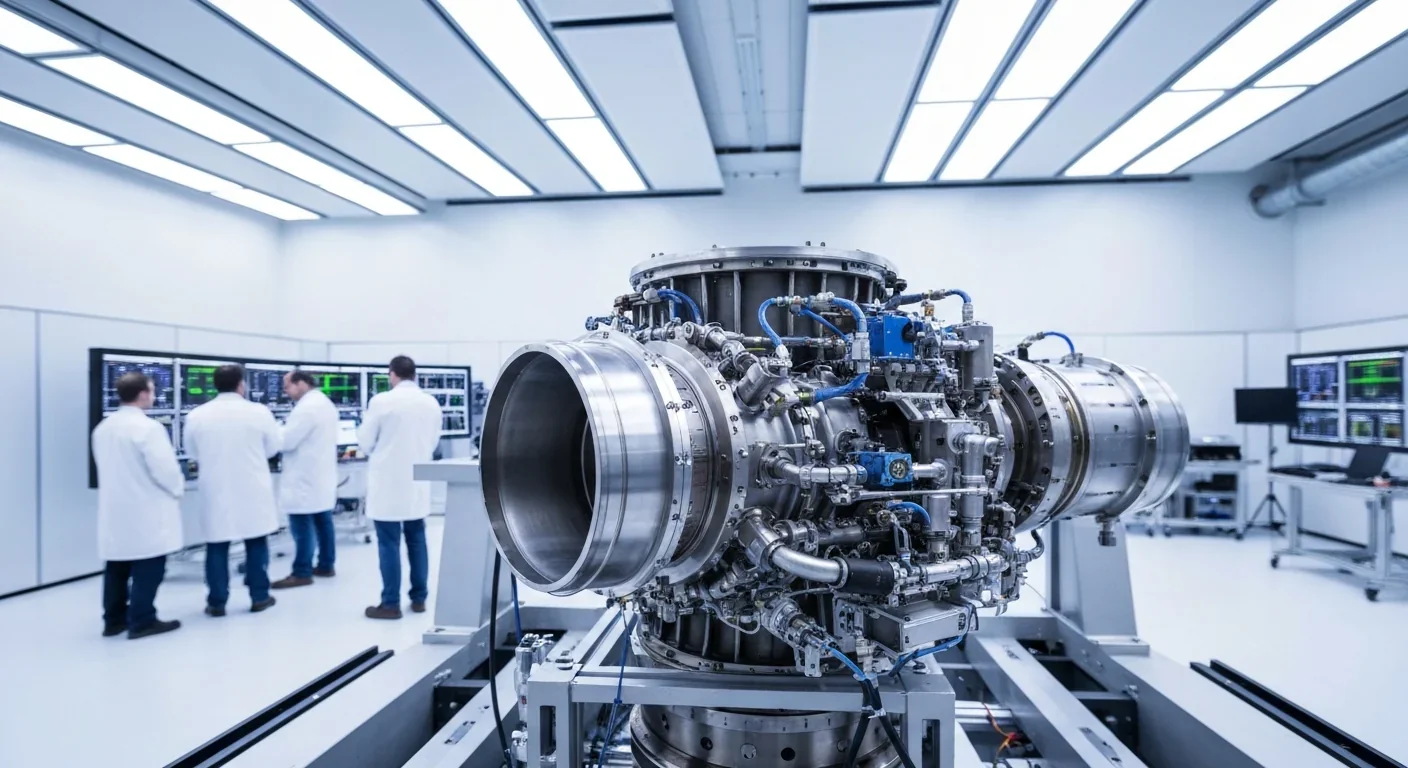

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

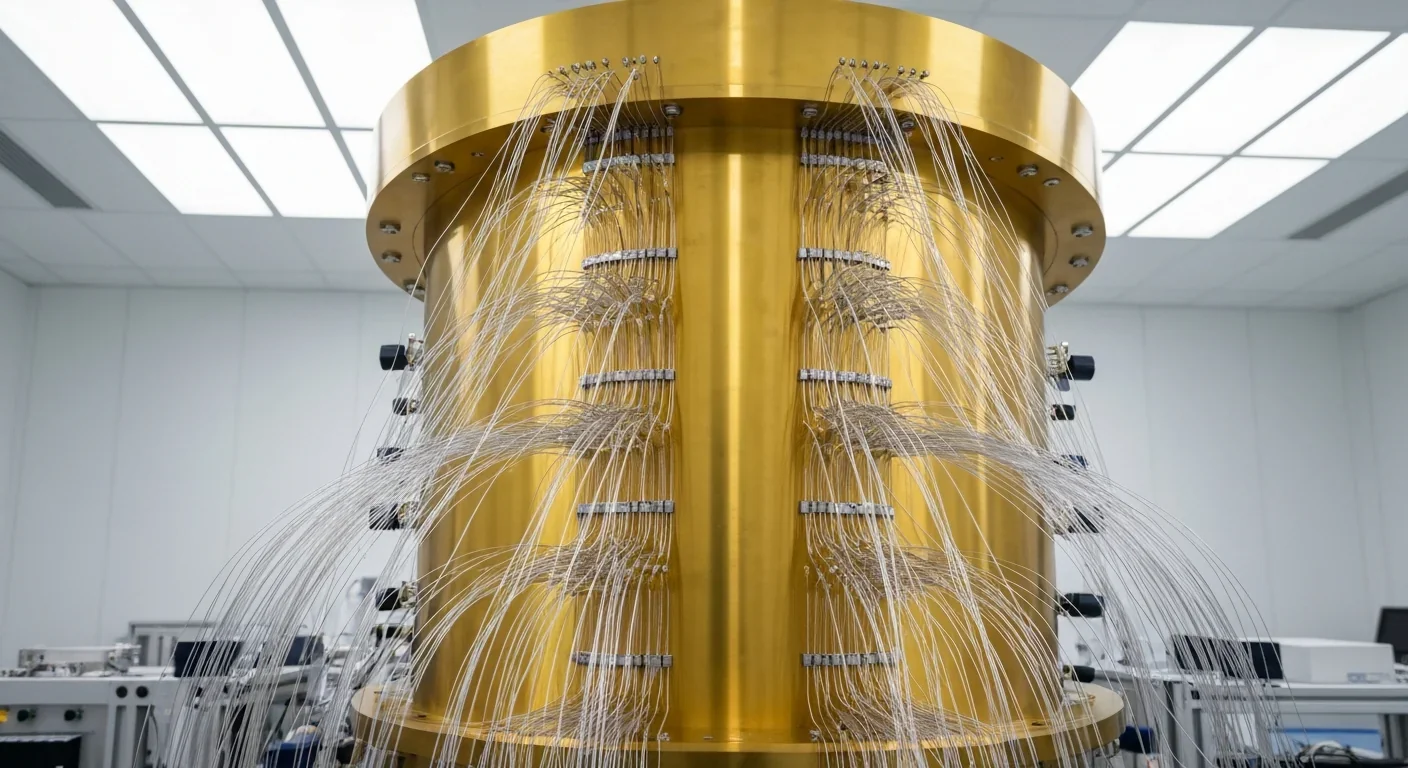

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.