Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: Lysosomal storage diseases occur when genetic mutations disable the cellular recycling system, causing toxic waste to accumulate and damage organs. Gene therapy trials show unprecedented promise, with some patients discontinuing enzyme replacement therapy for months while maintaining health - offering hope for conditions once considered untreatable.

Inside every cell in your body, a microscopic recycling system works around the clock, breaking down proteins, fats, and cellular debris so your body can reuse them. But for roughly 1 in 7,000 newborns, this cellular cleanup crew doesn't function properly, leading to a devastating cascade of failures that can reshape families and challenge the boundaries of modern medicine.

Lysosomal storage diseases represent what happens when biology's garbage disposal breaks down. These approximately 50 rare inherited disorders turn the body's recycling system into a trap, where cellular waste accumulates instead of being cleared. The result? Progressive damage to organs and tissues that often proves fatal in early childhood. Yet hidden within this tragedy is a frontier of medical innovation that's rewriting the rules for treating genetic diseases.

Think of lysosomes as the waste management department of your cells. These tiny, membrane-bound compartments contain more than 50 different enzymes, each specialized to break down specific types of molecular waste. Proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, old cell parts - all get recycled through this system, their building blocks released for reuse.

The beauty of this system lies in its specificity. Each enzyme has a job, like workers on an assembly line. Hexosaminidase A breaks down a fatty substance called GM2 ganglioside in nerve cells. Glucocerebrosidase handles a different lipid in various tissues. Alpha-galactosidase tackles yet another waste product.

When even one of these enzymes is missing or malfunctioning due to genetic mutations, the consequences ripple outward like a domino effect. The specific substance that enzyme was supposed to process starts accumulating. Week by week, month by month, these unprocessed materials pile up inside cells, distorting their shape, disrupting their function, and eventually killing them.

The lysosome becomes less of a recycling center and more of a toxic storage unit - hence the name "lysosomal storage diseases."

Nearly all lysosomal storage diseases follow an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, meaning a child must inherit a defective gene from both parents to develop the disease. If both parents are carriers - each possessing one mutated gene copy alongside one normal copy - each of their children faces a 25% chance of inheriting two mutated copies and developing the disease.

This pattern creates a hidden genetic landscape. Carriers typically show no symptoms because their single functioning gene copy produces enough enzyme to keep cellular recycling running adequately. But when two carriers have children together, the genetic dice can turn cruel.

Population genetics adds another layer to this story. Certain populations show dramatically elevated carrier rates for specific LSDs due to founder effects - when a small group of ancestors carried a particular mutation, and generations of intermarriage within that community amplified its frequency. The most well-known example is Tay-Sachs disease in Ashkenazi Jewish communities, where approximately 1 in 30 individuals carries the mutation. Similar patterns appear in French Canadian populations and Louisiana Cajun communities.

Why would such harmful mutations persist? One controversial hypothesis suggests that carrier status may confer some protective advantage - perhaps resistance to tuberculosis in the case of Tay-Sachs. If carriers had slightly better survival rates historically, natural selection might have maintained these mutations at higher frequencies despite their devastating effects when inherited in pairs.

The approximately 50 lysosomal storage diseases fall into several categories based on the type of material that accumulates: sphingolipidoses (lipid accumulation), mucopolysaccharidoses (complex sugar accumulation), glycoproteinoses (protein-sugar compound accumulation), and others.

Tay-Sachs disease stands as one of the most heartbreaking examples. Infants appear normal at birth, but around 6 months, parents notice developmental regression. Babies who were starting to sit up lose that ability. They become less responsive, startle at sounds they previously ignored, and develop a characteristic "cherry-red spot" visible during eye exams. Progressive neurological deterioration continues relentlessly. Most children die by age four, often from pneumonia as respiratory muscles weaken.

Gaucher disease shows remarkable variability. Type 1 - the most common form - may not appear until adulthood, causing enlarged liver and spleen, bone pain, and fatigue but sparing the brain. Types 2 and 3 involve neurological damage, with Type 2 proving rapidly fatal in infancy. This wide spectrum exists because more than 300 different mutations can affect the glucocerebrosidase enzyme, each producing varying levels of residual enzyme activity.

"The lysosome is commonly referred to as the cell's recycling center because it processes unwanted material into substances that the cell can use."

- Wikipedia, Lysosomal Storage Disease

Pompe disease demonstrates how LSDs can affect specialized tissues differently. The deficient enzyme - acid alpha-glucosidase - causes glycogen to accumulate primarily in muscle cells. Infantile-onset Pompe presents with severe muscle weakness and a dangerously enlarged heart, typically proving fatal before age two without treatment. Late-onset forms may not appear until adulthood, causing progressive muscle weakness that gradually steals mobility and eventually respiratory function.

Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS disorders) like Hunter syndrome and Sanfilippo syndrome cause accumulation of complex sugars called glycosaminoglycans. Children develop distinctive facial features, skeletal abnormalities, organ enlargement, and progressive cognitive decline. Each MPS type targets different tissues with varying severity, but most involve multiple organ systems.

Fabry disease can remain undiagnosed for years because early symptoms - pain in hands and feet, heat intolerance, gastrointestinal issues - seem unconnected. Over decades, the accumulated lipid globotriaosylceramide damages kidneys, heart, and brain, leading to organ failure in middle age.

The common thread? These diseases don't just affect one organ - they create cascading failures across multiple systems because lysosomes exist in nearly every cell type.

The lethality of lysosomal storage diseases stems from several factors working in terrible concert.

First, accumulation is irreversible without intervention. Unlike many diseases where the body can heal once the underlying problem is addressed, LSDs involve permanent storage of materials that cells cannot eliminate on their own. Each day adds to the toxic burden.

Second, critical organ systems take devastating hits. When LSDs affect the brain - as many do - neurological damage proves especially catastrophic. The central nervous system has limited capacity for repair, and neurons packed with storage material simply die. In diseases like Tay-Sachs, progressive neurodegeneration robs children of every skill they've gained, then strips away basic functions like breathing and swallowing.

When LSDs target the heart, as in infantile Pompe disease, cardiac muscle becomes so infiltrated with glycogen that it loses its ability to pump effectively. Cardiomegaly - dangerous heart enlargement - often proves fatal before age two.

The blood-brain barrier prevents most large molecules - including therapeutic enzymes - from entering the brain, making treatment of neurological LSDs extraordinarily difficult.

Third, current treatments have significant limitations. The gold-standard enzyme replacement therapy works beautifully for some LSDs but fails for others due to a critical obstacle: the blood-brain barrier. This protective shield prevents most large molecules - including therapeutic enzymes - from entering the brain. For LSDs with neurological involvement like Tay-Sachs, delivering enzyme to the brain remains extraordinarily difficult, even when infused directly into cerebrospinal fluid.

Fourth, diagnosis often comes too late. By the time symptoms prompt investigation and testing confirms an LSD, irreversible damage may have already occurred. This timing problem makes early intervention - when it might prevent the most severe outcomes - extremely challenging.

Recognizing LSDs requires vigilance because early symptoms often appear nonspecific. A child might simply seem to develop more slowly than peers, or experience unexplained pain, or show behavioral changes. Pediatricians may initially attribute these signs to more common developmental variations.

Several diagnostic tools help confirm LSDs once suspected:

Enzyme activity assays measure how much of a specific lysosomal enzyme is present in blood, skin cells, or other tissues. Severely reduced or absent activity points toward a specific LSD. Cleveland Clinic notes that in classic Tay-Sachs disease, hexosaminidase A is essentially absent from blood samples.

Genetic testing identifies the specific mutations responsible. This approach proves particularly valuable for carrier screening in high-risk populations, enabling couples to understand their risks before conceiving. DNA sequencing can detect more than 100 different HEXA mutations associated with Tay-Sachs alone.

Biomarker analysis detects accumulated substances in blood or urine. For mucopolysaccharidoses, measuring glycosaminoglycan levels in urine provides diagnostic clues about which specific MPS disorder is present.

Imaging studies reveal organ enlargement, skeletal abnormalities, and brain changes characteristic of particular LSDs. MRI scans may show white matter abnormalities in metachromatic leukodystrophy, while X-rays display the distinctive bone changes of MPS disorders.

Newborn screening represents the frontier in early diagnosis. Some states now include tests for Pompe disease, MPS I, and other LSDs in their mandatory newborn screening panels. Early detection through screening enables treatment to begin before irreversible damage occurs, dramatically improving outcomes for certain LSDs.

The therapeutic approach to LSDs has evolved from purely supportive care to disease-modifying interventions, though significant gaps remain.

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) delivers functional copies of the missing enzyme intravenously. For several LSDs - including Gaucher disease Type 1, Pompe disease, Fabry disease, and several MPS disorders - ERT has transformed outcomes. Patients receive infusions every one to two weeks, supplying their cells with the enzyme they cannot produce.

The success stories are remarkable. Gaucher disease Type 1, once severely debilitating, now allows patients to lead relatively normal lives with regular ERT. Infantile Pompe disease, previously uniformly fatal before age two, now sees children surviving into school age and beyond with treatment started shortly after birth.

"While enzyme replacement therapies enhance survival by tackling cardiac issues, they fall short in addressing skeletal muscle and central nervous system complications."

- DelveInsight, Pompe Disease Analysis

But ERT has critical limitations. The infused enzymes cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, rendering ERT ineffective for LSDs with central nervous system involvement. Even direct injection into cerebrospinal fluid fails for conditions like Tay-Sachs because the hexosaminidase A molecule is simply too large to penetrate brain tissue from the spinal fluid. Additionally, some patients develop immune responses against the infused enzyme, reducing its effectiveness over time.

Substrate reduction therapy takes a different approach: if you can't break down the accumulating material, slow its production. Medications like miglustat inhibit the synthesis of the storage material, reducing accumulation. While not a cure, this strategy helps some Gaucher patients and offers an oral medication alternative to infusions.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) replaces the patient's blood-forming stem cells with donor cells carrying functional genes. The transplanted cells produce the missing enzyme, which can then be taken up by other cells throughout the body. For some MPS disorders and other LSDs, HSCT performed early can slow or halt disease progression, though it carries significant risks including graft rejection and infection.

Pharmacological chaperone therapy uses small molecules that stabilize misfolded enzymes, helping them function more effectively. For Fabry disease, migalastat helps certain mutations of alpha-galactosidase fold properly and reach lysosomes where they can work.

Supportive care remains essential across all LSDs. Managing symptoms - treating seizures, providing nutritional support, addressing pain, preventing infections - improves quality of life even when disease-modifying therapies aren't available.

Gene therapy represents the most exciting frontier in LSD treatment, offering the prospect of durable or permanent correction rather than lifelong enzyme replacement.

The principle is elegant: deliver a functional copy of the defective gene into the patient's cells using a modified virus as a vehicle. Once inside, the gene integrates into cellular machinery and begins producing the missing enzyme. Done successfully, this could provide a one-time treatment with lasting benefits.

Adeno-associated viruses (AAV) have emerged as the preferred delivery vehicle. These modified viruses efficiently infect human cells but don't cause disease and generally don't integrate into chromosomes where they might disrupt important genes. Different AAV serotypes naturally target different tissues - AAV9 crosses the blood-brain barrier, making it useful for LSDs with neurological involvement, while AAV8 preferentially targets muscle and liver.

Recent clinical trials are generating unprecedented optimism:

In Tay-Sachs disease, a 2022 gene therapy trial delivered the correct HEXA gene directly to brain cells of two children using AAV9. Both showed functional improvements compared to the natural disease course - a first for this invariably fatal condition.

For Pompe disease, multiple gene therapy candidates are in trials. ACTUS-101 uses AAV to deliver the GAA gene to muscle cells, potentially replacing the need for bi-weekly enzyme infusions. Even more striking, AT845 gene therapy has allowed some patients to discontinue ERT entirely for periods of 19 to 51 weeks while maintaining stable function - strong evidence that gene therapy can provide sustained enzyme production.

Gene therapy trials show patients discontinuing enzyme replacement therapy for up to 51 weeks while maintaining stable function - a breakthrough moment for LSDs.

MPS IIIA (Sanfilippo syndrome A), one of the most devastating childhood dementias, is being targeted by UX111. This AAV9-based therapy showed rapid reductions in biomarkers of disease activity in cerebrospinal fluid when administered before advanced neurodegeneration.

GM1 gangliosidosis, another fatal neurological LSD, is being addressed by PBGM01, delivered via injection directly into the brain's cerebrospinal fluid spaces. Early trial data shows dose-dependent increases in enzyme activity in the central nervous system.

The challenges are significant. AAV-based gene therapies can trigger immune responses, potentially reducing efficacy or causing inflammation. Manufacturing these therapies at scale while maintaining quality proves complex and expensive. And for LSDs where damage has already occurred, gene therapy may halt progression but cannot reverse existing injury.

Still, the trajectory is clear. Gene therapy is moving from experimental concept to clinical reality for LSDs, offering hope where little existed before.

Beyond gene therapy, researchers are exploring multiple avenues to combat LSDs.

CRISPR gene editing offers the theoretical possibility of correcting mutations directly in patients' cells rather than simply adding a functional gene copy. While still in early development for LSDs, the technology's precision could eventually overcome some limitations of current gene therapy approaches.

Small molecule therapies aim to achieve various goals: enhancing enzyme stability, facilitating enzyme trafficking to lysosomes, or reducing inflammation and secondary damage. Ambroxol, a common cough medicine, has shown promise for increasing glucocerebrosidase activity in Gaucher disease and may even benefit Parkinson's disease patients who often carry Gaucher mutations.

Blood-brain barrier disruption techniques could help therapeutic enzymes reach the brain. Focused ultrasound can temporarily open the blood-brain barrier in targeted regions, potentially allowing ERT to access brain tissue that would otherwise remain untreated.

Prenatal and preimplantation diagnosis enables couples at risk to test embryos or fetuses for LSD mutations. Combined with IVF and preimplantation genetic testing, couples who are both carriers can ensure they have unaffected children. This approach has dramatically reduced Tay-Sachs incidence in communities where carrier screening and genetic counseling are widely available.

Newborn screening expansion continues to add more LSDs to mandatory screening panels. Early detection enables earlier treatment, which proves crucial for conditions where outcomes depend critically on timing. Children's Hospital of Orange County and other centers of excellence are developing rapid testing protocols that compress diagnosis timelines from months to days.

The treatment landscape for lysosomal storage diseases is shifting faster than most rare disease fields. A generation ago, these conditions were largely untreatable. Today, multiple LSDs have approved enzyme replacement therapies, and gene therapy is transitioning from hypothesis to clinical tool.

Within the next decade, we'll likely see:

More gene therapies reaching approval, expanding the number of LSDs with one-time treatment options. The FDA has signaled willingness to approve gene therapies based on biomarker and functional outcomes rather than requiring decades of survival data.

Combination approaches that pair gene therapy with immunosuppression to prevent rejection, enzyme replacement to manage disease during gene therapy's ramp-up period, or small molecules to enhance gene therapy efficacy.

Neonatal gene therapy, where newborns diagnosed through screening receive gene therapy within days of birth, preventing damage before it starts. Early trials in MPS disorders are testing whether this approach can essentially cure diseases that would otherwise devastate development.

Ex vivo gene therapy, where patients' own stem cells are removed, genetically corrected in the laboratory, and reinfused - combining the advantages of gene therapy and stem cell transplantation without rejection risk.

The economic and access challenges remain substantial. Gene therapies often cost millions of dollars per patient, raising questions about healthcare system capacity and global equity. A therapy that works brilliantly but remains available only to wealthy patients in developed countries fails the broader ethical test.

For families affected by lysosomal storage diseases, the advances can feel simultaneously revolutionary and achingly slow. Each trial result, each approval, each new therapy carries the weight of desperate hope.

Organizations like the National Organization for Rare Disorders and disease-specific foundations provide critical support: funding research, connecting families, advocating for newborn screening expansion, and ensuring that even as science advances, the human needs of affected families don't get lost.

The medical community is learning that comprehensive care for LSDs extends beyond drugs and gene therapy. Coordinated multidisciplinary teams - metabolic specialists, neurologists, cardiologists, genetic counselors, nutritionists, physical therapists, and psychosocial support staff - improve outcomes and reduce family burden by addressing the complex, evolving needs these diseases create.

Research into LSDs has implications beyond these rare conditions. Understanding how cells manage their waste products illuminates more common diseases. The lysosomes and lipids involved in Gaucher disease, for instance, intersect with Parkinson's disease pathways - Gaucher mutations increase Parkinson's risk, and treatments for one condition might inform the other.

The gene therapy techniques pioneered for LSDs are being adapted for other genetic diseases, from hemophilia to muscular dystrophy. Success in LSDs - where single-gene defects create clear treatment targets - establishes proof of principle for tackling more complex genetic conditions.

Perhaps the deepest lesson of lysosomal storage diseases lies in what they reveal about biological systems. Our cells function through countless interconnected processes, each dependent on others, each vulnerable to disruption. The failure of a single enzyme - one protein among thousands - can topple the entire system.

But the same interconnection that creates vulnerability also offers therapeutic opportunity. Gene therapy works precisely because cells have machinery to take up DNA, express new genes, and distribute proteins throughout the body. Enzyme replacement succeeds because cells evolved to capture and use enzymes from their surroundings. The blood-brain barrier that blocks treatments also protects the delicate neural tissue we're trying to save.

These diseases, devastating as they are, have taught medicine how to intervene at the most fundamental levels of biology. The children and families affected by LSDs have contributed immeasurably to scientific progress, often participating in early trials knowing the personal benefit might be small but the knowledge gained could help others.

As research continues, the distinction between "rare" and "common" disease may blur. The mechanisms causing rare LSDs often echo in more prevalent conditions. The treatments developed for small patient populations demonstrate what's possible in genetic medicine broadly.

The cellular recycling system that fails in LSDs usually works with remarkable reliability across billions of cells and decades of life. When it fails, the consequences unfold with tragic clarity. But the same clarity that makes these diseases devastating also makes them scientifically tractable - single genes, specific enzymes, measurable substrates. In that tractability lies hope: that rare diseases once considered medical dead ends might become among the first genetic conditions we learn to truly cure.

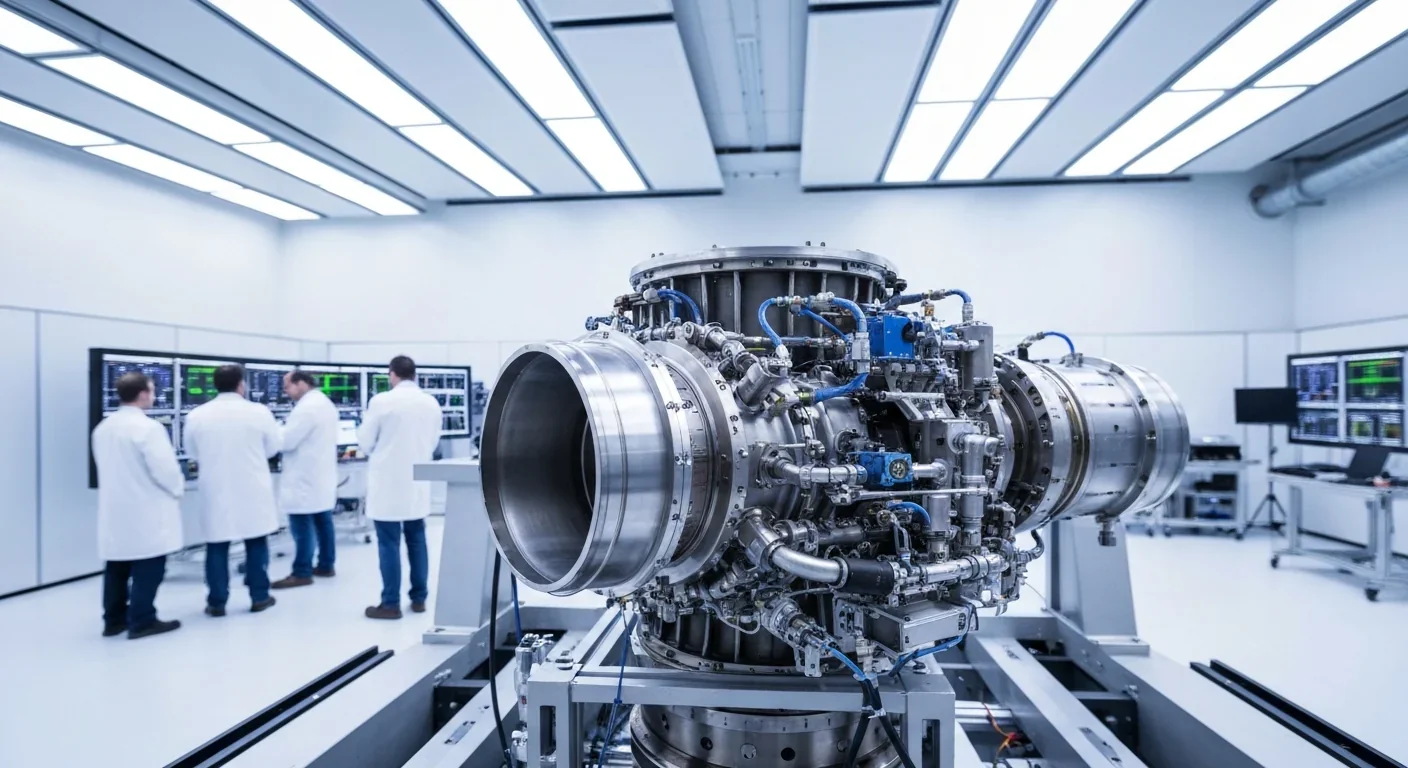

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

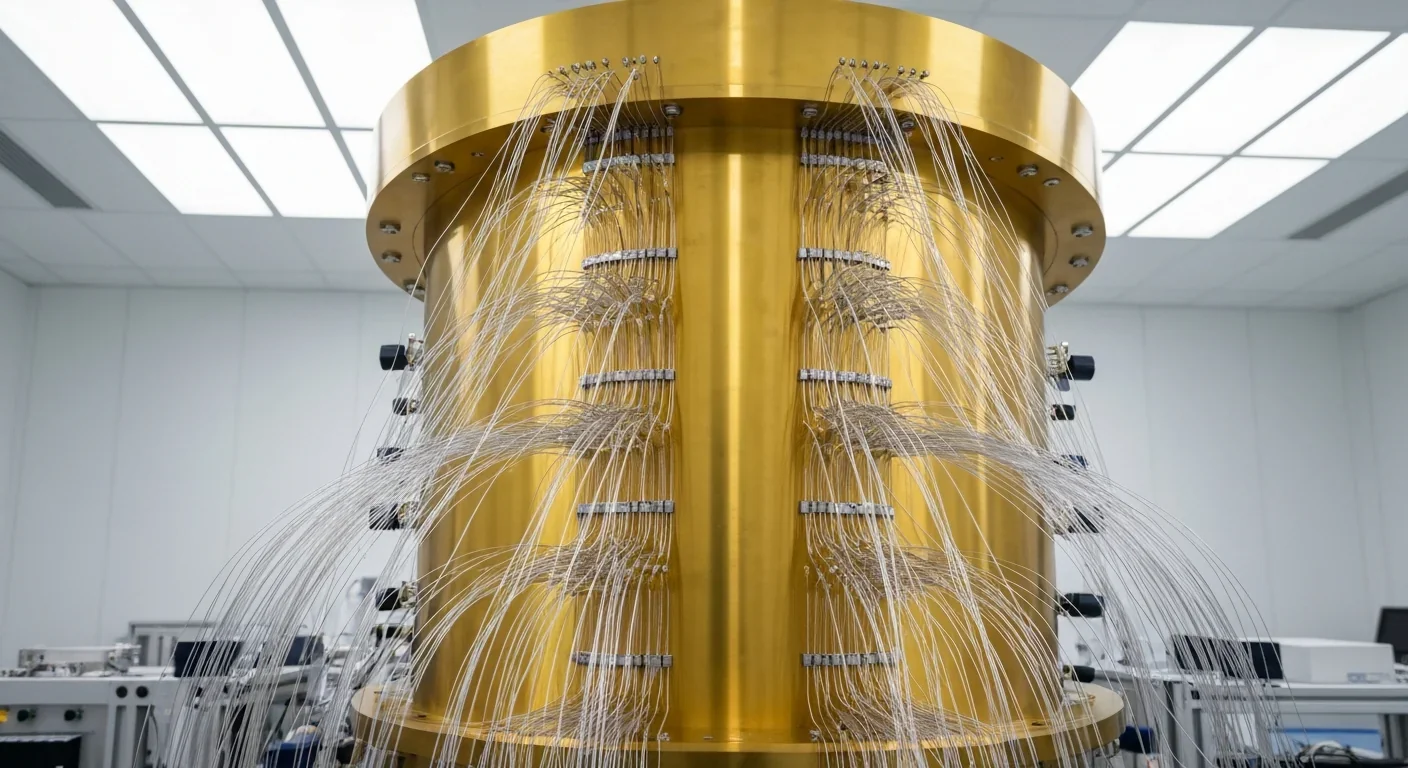

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.