The Ancient Protein Clock That Ticks Without DNA

TL;DR: Up to 25% of Americans now experience chemical sensitivities triggered by everyday petrochemical exposure. Research reveals mast cell dysregulation and neurological changes as biological mechanisms behind Multiple Chemical Sensitivity, an emerging epidemic with serious public health implications.

Walk through any grocery store, office building, or parking garage, and you're swimming through an invisible sea of petrochemicals. Perfumes from the woman at the checkout. VOCs off-gassing from new carpet. Exhaust fumes in the parking lot. For most people, these are just background annoyances. But for a rapidly growing number, they trigger debilitating symptoms that make normal life nearly impossible.

Scientists now have a name for this: Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS), also known as Chemical Intolerance Syndrome or Toxicant-Induced Loss of Tolerance (TILT). And the evidence suggests we're looking at a petrochemical-driven epidemic hiding in plain sight.

The numbers are startling. Between 12-25% of Americans now report some degree of chemical sensitivity, with prevalence rates climbing year after year. In Canada, 3.3% of women meet the criteria for MCS. In Australia, it's 6.5% of adults. These aren't people with rare genetic disorders or exotic occupational exposures. They're your neighbors, coworkers, family members.

What makes MCS particularly insidious is how it develops. You don't wake up one day allergic to modern life. Instead, there's typically an initiating exposure, often to high levels of petrochemical byproducts, pesticides, or industrial chemicals. This initial hit appears to fundamentally alter how your body processes chemicals going forward.

Think of it like maxing out a credit card. For years, your body handles chemical exposures fine, breaking them down, neutralizing them, eliminating them. But then you hit a threshold. Maybe it's a renovation project where you're breathing paint fumes and off-gassing carpet for weeks. Maybe it's an occupational exposure in a salon or factory. Or maybe it's just the cumulative burden of living in a petrochemical-saturated world.

Once sensitized, your body's tolerance collapses. Exposures you previously handled without issue now trigger cascading symptoms: headaches, fatigue, brain fog, respiratory distress, and nausea.

Once you cross that line, your body's tolerance collapses. Suddenly, exposures you previously handled without issue, perfume in an elevator, diesel exhaust, scented laundry detergent, trigger a cascade of symptoms. Headaches. Fatigue. Brain fog. Respiratory distress. Nausea. The list goes on.

For decades, MCS was dismissed as psychosomatic, something anxious people imagined. But recent research has identified concrete biological mechanisms that explain what's happening at a cellular level.

The smoking gun appears to be mast cells, specialized white blood cells that sit at the frontline of your immune response. When functioning normally, mast cells help defend against pathogens and coordinate healing. But petrochemical exposure can dysregulate them, putting them into a state of chronic hyperactivation.

"Parents who have a high degree of chemical intolerance were nearly six times more likely to report having a child diagnosed with autism and over two times more likely to have a child diagnosed with ADHD."

- Journal of Xenobiotics, 2024

A 2024 study in the Journal of Xenobiotics found that parents with high chemical intolerance were nearly six times more likely to have children with autism and over twice as likely to have children with ADHD. The researchers identified mast cells as "a plausible biomechanism for chemical intolerance," capable of undergoing gene activation or deactivation, with effects potentially transmitted across generations.

This isn't just inflammation in the traditional sense. It's more like your immune system has recalibrated its threat detection system, and now it's seeing danger everywhere. The process involves what researchers call endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, a cellular stress response that occurs when proteins can't fold properly. Petrochemical exposures trigger ER stress, which activates the unfolded protein response, leading to inflammation, cell death, and, critically, immune dysregulation.

Imaging studies have revealed something even more profound: MCS appears to be a neurological condition. The olfactory nerve, your sense of smell, provides a direct highway from the environment into your brain, bypassing the blood-brain barrier. When you smell a petrochemical, that signal travels through the olfactory bulb to the amygdala and limbic system, brain regions involved in emotion and threat response. In people with MCS, this pathway becomes hypersensitive.

The reaction can be immediate, within seconds of detecting an odor, too fast for systemic absorption. This rules out classic toxicological poisoning and points instead to a neurological sensitization, your brain learning to interpret chemical exposures as existential threats and mounting a full-body defense response.

Here's where it gets truly concerning: petrochemical derivatives are everywhere. Not just in obvious places like gas stations and industrial sites, but woven into the fabric of modern existence.

Consider your morning routine. Your shampoo, body wash, and moisturizer likely contain phthalates (plasticizers), parabens (preservatives), and synthetic fragrances, all petrochemical derivatives. Your non-stick pan releases PFAS ("forever chemicals") when heated. Your furniture and carpet off-gas flame retardants like PBDEs. Your car's dashboard releases phthalates and VOCs, especially when sitting in the sun.

A 2025 UC Davis study tested 201 preschool-age children and detected 34 chemicals in more than 90% of them. These weren't kids living near Superfund sites. These were ordinary American children accumulating body burdens of phthalates, parabens, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), a class of petrochemical combustion byproducts, just from normal daily life.

Indoor house dust alone contributes up to 82% of humans' PBDE body burden. You literally breathe and ingest petrochemical residues every day.

Indoor house dust alone contributes up to 82% of humans' PBDE body burden. You literally breathe and ingest petrochemical residues every day, in your home, at levels that exceed outdoor air pollution.

MCS doesn't strike randomly. Certain populations show significantly higher susceptibility.

Women are disproportionately affected, representing the majority of MCS cases. The typical onset is around middle age, though cases are increasingly appearing in younger people. Interestingly, people with MCS tend to have higher socioeconomic status and education levels, possibly because they're more attuned to their symptoms and more likely to seek medical explanation.

Occupational exposures create obvious risk. Beauty salon workers, who inhale aerosolized cosmetics daily, show elevated rates of respiratory sensitization and chemical intolerance. The same pattern appears in painters, cleaning staff, factory workers, and anyone with chronic exposure to solvents, pesticides, or industrial chemicals.

Children face unique vulnerability. Their bodies are still developing, their detoxification systems are immature, and pound-for-pound they breathe more air, drink more water, and eat more food than adults, meaning higher dose-normalized exposures. The UC Davis study found that children from racial and ethnic minority groups had significantly higher levels of parabens, phthalates, and PAHs, pointing to environmental justice dimensions of the crisis.

Veterans, particularly Gulf War veterans, represent another high-risk group. Dose-response evidence shows that higher pesticide use during the Gulf War correlates with stronger Gulf War illness symptoms. Oil well fire emissions caused both neurotoxicity and immune dysregulation, leading to chronic neurological and systemic symptoms that closely mirror MCS.

Genetic susceptibility also plays a role. Variations in genes controlling cytochrome P450 enzymes, which metabolize many petrochemicals, can leave some people less able to detoxify exposures. Similarly, variations in genes controlling inflammation, oxidative stress response, and blood-brain barrier function may increase MCS risk.

Perhaps the cruelest aspect of MCS is the medical gaslighting. MCS remains an unrecognized and controversial diagnosis in mainstream medicine. There's no standard diagnostic test, no FDA-approved treatment, and limited insurance coverage for care.

Part of the problem is that MCS doesn't fit neatly into existing medical categories. It's not an allergy in the immunological sense (no IgE antibodies). It's not classic poisoning (symptoms occur at exposures well below established toxicological thresholds). It involves multiple organ systems and can be triggered by chemically unrelated substances, defying simple mechanistic explanation.

"Very little rigorous peer-reviewed research exists into MCS, though Italian, Danish, and Japanese research has begun identifying neurobiologic, metabolic, and genetic susceptibility factors."

- Canadian Government Task Force on Environmental Health, 2017

A 2017 Canadian government Task Force on Environmental Health reported very little rigorous peer-reviewed research into MCS, though Italian, Danish, and Japanese research has begun identifying neurobiologic, metabolic, and genetic susceptibility factors. The scientific literature is growing, but medical education hasn't caught up.

Many doctors, lacking training in environmental medicine, default to psychiatric explanations. Patients are told their symptoms are anxiety, depression, or somatic symptom disorder. While psychological factors can certainly modulate symptom severity, dismissing MCS as purely psychiatric ignores the biomarker and neuroimaging evidence of biological disturbances.

The comorbidity with mental health conditions is real, MCS patients do show higher rates of PTSD, depression, chronic fatigue syndrome, and fibromyalgia, but this likely reflects shared underlying mechanisms (chronic inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroendocrine disruption) rather than proving psychological causation. Trauma and stress can lower tolerance thresholds, but they're not inventing the chemical exposures.

To understand how petrochemical exposure leads to MCS, researchers have developed the TILT model: Toxicant-Induced Loss of Tolerance.

Stage 1: Initiation. A high-level exposure or chronic low-level exposure to fossil fuel derivatives, pesticides, or other toxicants triggers a fundamental shift in how your body processes chemicals. This might happen during a renovation, a pesticide spraying, an industrial accident, or through cumulative occupational exposure. At the cellular level, this initiation phase involves epigenetic changes, alterations in gene expression that persist long after the initial exposure ends.

Stage 2: Triggering. Once sensitized, previously tolerated exposures now trigger symptoms. The threshold is massively lowered. A whiff of perfume that never bothered you before now causes a migraine. Diesel exhaust that you barely noticed now leaves you with respiratory distress and brain fog. The triggering exposures don't have to be chemically related to the initiating toxicant, someone sensitized by pesticide exposure might react to fragrances, and vice versa.

This two-stage model explains why MCS often has an identifiable onset (the initiation event) followed by expanding sensitivity to multiple chemical classes (the triggering phase). It also explains why simply avoiding the original trigger doesn't cure the condition, the damage is done, tolerance is lost.

Many petrochemical byproducts don't just trigger immune and neurological reactions. They also act as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), interfering with hormonal signaling throughout the body.

Phthalates mimic estrogen. PFAS interferes with thyroid function. Flame retardants disrupt reproductive hormones. These aren't theoretical concerns, they're documented in hundreds of peer-reviewed studies. The WHO and UN Environment Programme identified major gaps in EDC knowledge in 2013 and called for more research on mixtures of EDCs from industrial byproducts, exactly the kind of complex real-world exposures people with MCS face.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals can act at incredibly low doses, sometimes showing stronger effects at low doses than high ones, a phenomenon called non-monotonic dose response.

EDCs can act at incredibly low doses, sometimes showing stronger effects at low doses than high ones (non-monotonic dose responses). They can have effects during critical developmental windows (prenatal, early childhood, puberty) that don't manifest until years later. And they interact with each other in unpredictable ways, a mixture of five weak EDCs might have effects that none of them would alone.

This means the safe dose paradigm underlying regulatory toxicology, the dose makes the poison, may not apply. Some petrochemical byproducts may cause harm at any dose, particularly during vulnerable developmental windows or in people with genetic or acquired susceptibility.

For people with severe MCS, modern life becomes a minefield. MCS is a chronic disease that requires ongoing management, and that management essentially means avoidance.

Fragrance-free personal care products. No air fresheners or scented candles. Avoiding public spaces where others wear perfume. Carefully vetting household products for VOCs and off-gassing. Installing HEPA and activated carbon air filtration. In severe cases, people become effectively homebound, unable to work, shop, or socialize without triggering debilitating reactions.

The social isolation compounds the physical illness. Friends and family often don't understand, they can't smell what you smell or feel what you feel, and requests to avoid perfume or change laundry detergent can come across as controlling or neurotic. Employers may see accommodation requests as unreasonable. The medical establishment offers limited validation or support.

Even home isn't always a safe refuge. Neighbors' dryer vents expel scented detergent and fabric softener chemicals. Outdoor air brings traffic exhaust, lawn pesticides, and wildfire smoke laden with PAHs. New construction or renovations can release off-gassing that permeates whole neighborhoods.

The burden of petrochemical exposure falls unequally. The UC Davis study showing higher phthalate, paraben, and PAH levels in minority children isn't an accident. It reflects systematic disparities in exposure.

Low-income communities and communities of color are more likely to be located near industrial facilities, highways, and waste sites. They're more likely to live in older housing with lead paint and mold. They have less access to organic food, HEPA filtration, and low-toxicity consumer products. When illness strikes, they have less access to specialists in environmental medicine and less ability to make the lifestyle changes MCS demands.

The recent 3M settlement of $10.3 billion for PFAS contamination of U.S. drinking water highlights how petrochemical pollution has become infrastructure-level, embedded in the water, soil, and air of entire communities. Avoiding exposure isn't just a matter of consumer choice when your municipal water supply is contaminated.

A systematic review protocol investigating MCS validity, prevalence, tools, and interventions highlights how little rigorous research exists. The protocol itself, a plan to review existing evidence, underscores the knowledge gaps.

We don't have large-scale longitudinal studies tracking who develops MCS and why. We don't have validated biomarkers for diagnosis. We don't have effective treatments beyond avoidance. We don't have robust data on the economic costs or disability burden. We don't have regulatory standards that protect sensitive populations.

Part of this is funding. Environmental health research competes with sexy, high-profile disease research. Part is complexity, MCS involves multiple body systems, genetic and environmental factors, and individual variation that makes controlled studies difficult. And part is industry opposition, serious investigation of petrochemical health effects threatens highly profitable sectors.

Even if you don't have MCS, this research should concern you. Chemical tolerance isn't binary, it's a spectrum. Subclinical sensitivity is likely far more common than diagnosed MCS. You might attribute your afternoon headaches to stress, your fatigue to aging, your brain fog to lack of sleep, when petrochemical exposures could be contributory.

The dose-response evidence from Gulf War illness research, higher pesticide exposure predicting stronger symptoms, suggests no clear safe threshold. The generational effects suggested by the autism-chemical intolerance study point to epigenetic changes that could affect your children and grandchildren. The endocrine disruption research shows effects at environmental levels we all experience.

We're running an uncontrolled experiment, releasing tens of thousands of synthetic chemicals into commerce with minimal safety testing, then waiting to see what happens to human health. MCS might be the canary in the coal mine, an early warning that our petrochemical saturation has biological consequences.

While systemic solutions require policy change, individual protective measures can reduce exposure:

At home: Choose fragrance-free cleaning and personal care products. Avoid synthetic air fresheners and scented candles. When renovating, select low-VOC paints, formaldehyde-free materials, and solid wood over particleboard. Ventilate aggressively during and after any project. Consider HEPA and activated carbon filtration.

Food and water: Phthalates migrate from packaging into food, so minimize processed foods in plastic containers. Use glass or stainless steel instead of plastic. If you have PFAS in your water supply, investigate filtration options (reverse osmosis or activated carbon).

Consumer products: Be skeptical of anything with "fragrance" or "parfum" on the ingredient list, these can contain dozens of unlabeled petrochemical compounds. Watch out for flame retardants in furniture and electronics. Avoid non-stick cookware or at least don't overheat it.

Outdoors: Limit time in heavy traffic. Don't idle your car. Be aware of pesticide application schedules in your area. When wildfire smoke arrives, stay indoors with filtration running.

Medical advocacy: If you're experiencing unexplained multi-system symptoms triggered by chemical exposures, seek a physician trained in environmental medicine. Document your symptoms and exposure patterns. Don't accept dismissal without investigation.

Individual avoidance isn't enough. We need systemic change.

Regulatory reform: Current chemical safety regulation is reactive, substances are assumed safe until proven harmful. We need precautionary approaches that require safety demonstration before market entry, especially for persistent bioaccumulative toxicants. The EU's REACH program offers a model, though imperfect.

Recognition and accommodation: MCS needs formal medical recognition, standardized diagnostic criteria, and protection under disability law. Workplaces, schools, and public buildings should implement fragrance-free policies and reduce unnecessary chemical exposures.

Research funding: We need large-scale studies on MCS prevalence, mechanisms, biomarkers, and treatments. We need long-term cohort studies tracking petrochemical body burdens and health outcomes. We need research on chemical mixtures, not just individual compounds in isolation.

Environmental justice: Communities with high exposure need remediation, not just documentation. The burden of proof should shift, if your facility is releasing petrochemical pollution, you should have to demonstrate it's safe, not make exposed communities prove it's harmful.

Transparency: Chemical ingredients should be disclosed. "Fragrance" should not be allowed as a catch-all that hides proprietary mixtures. Consumers have a right to know what they're exposed to.

Multiple Chemical Sensitivity isn't a fringe phenomenon affecting a handful of unusually sensitive people. It's an emerging pattern of illness linked to ubiquitous petrochemical exposure, with plausible biological mechanisms, growing prevalence, and serious implications for public health.

The mast cell dysregulation, neurological sensitization, and epigenetic changes documented in recent research paint a picture of bodies overwhelmed by chemical exposures our biology never evolved to handle. The two-stage TILT model explains how a tipping point exposure can cause permanent loss of tolerance. The endocrine disruption research shows effects on development and reproduction that could ripple across generations.

We've built a society that runs on petrochemicals. They power our vehicles, heat our homes, and form the chemical backbone of countless consumer products. For decades, we've treated this as an unalloyed good, cheap energy and materials enabling modern prosperity.

But the health costs are coming due. MCS is likely just the most visible manifestation of a broader problem: chronic low-level petrochemical exposure affecting immune function, neurological health, endocrine balance, and metabolic regulation across entire populations.

The question isn't whether to completely eliminate petrochemicals tomorrow, that's neither feasible nor necessary. The question is whether we can acknowledge the accumulating evidence of harm and make the policy, economic, and personal choices to reduce unnecessary exposures.

Because the alternative, continuing to saturate our environment with biologically active synthetic chemicals while telling ourselves there's no problem, is a gamble with stakes we're only beginning to understand. And the people with MCS, living reminders that bodies have limits, are showing us what happens when we lose that bet.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

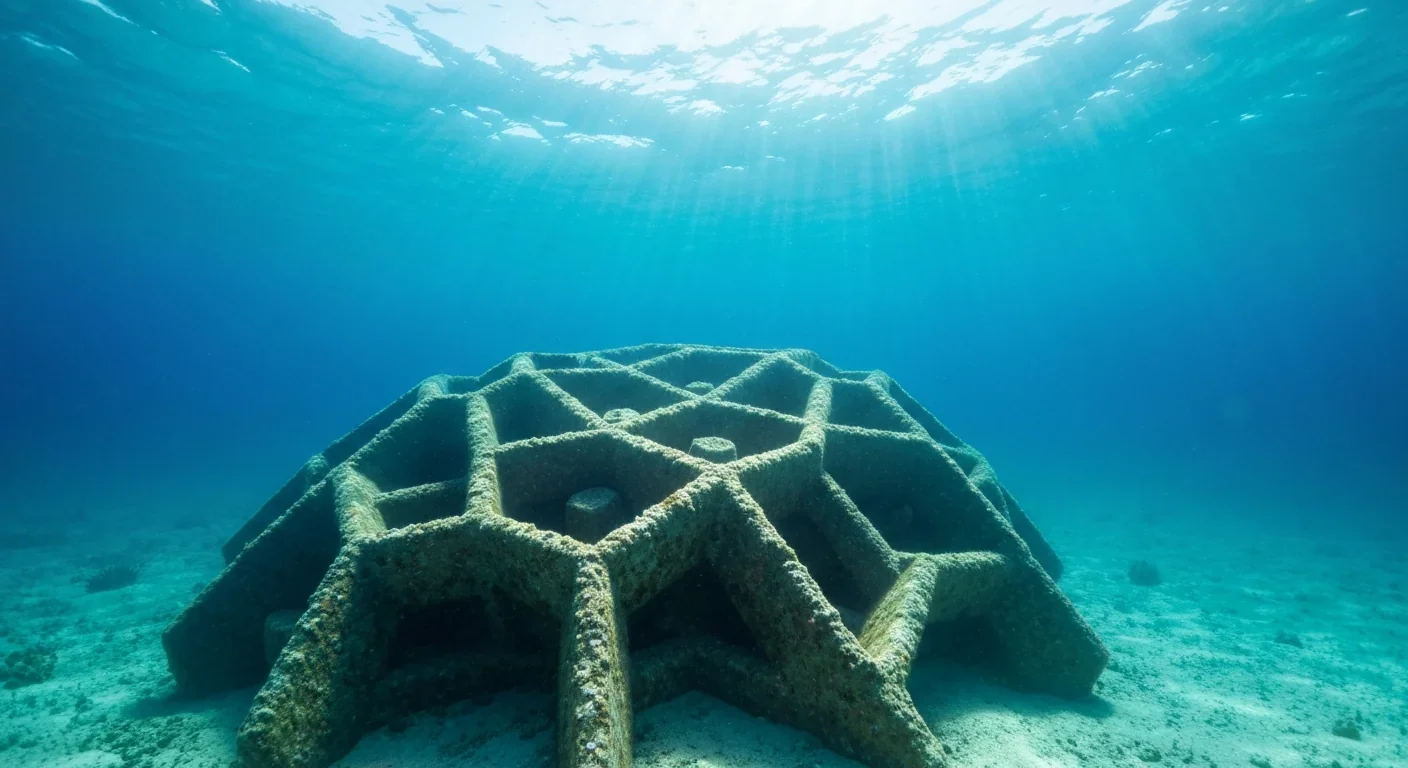

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

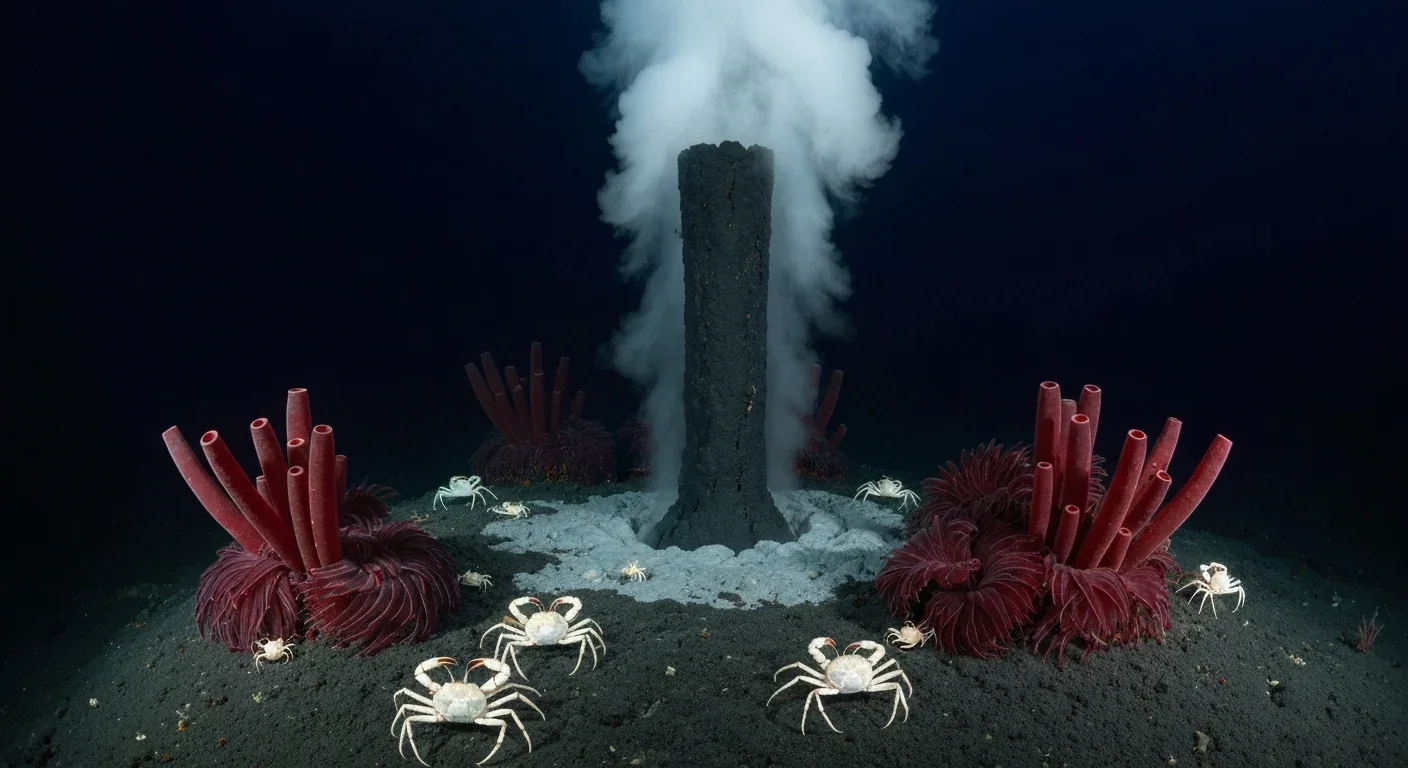

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

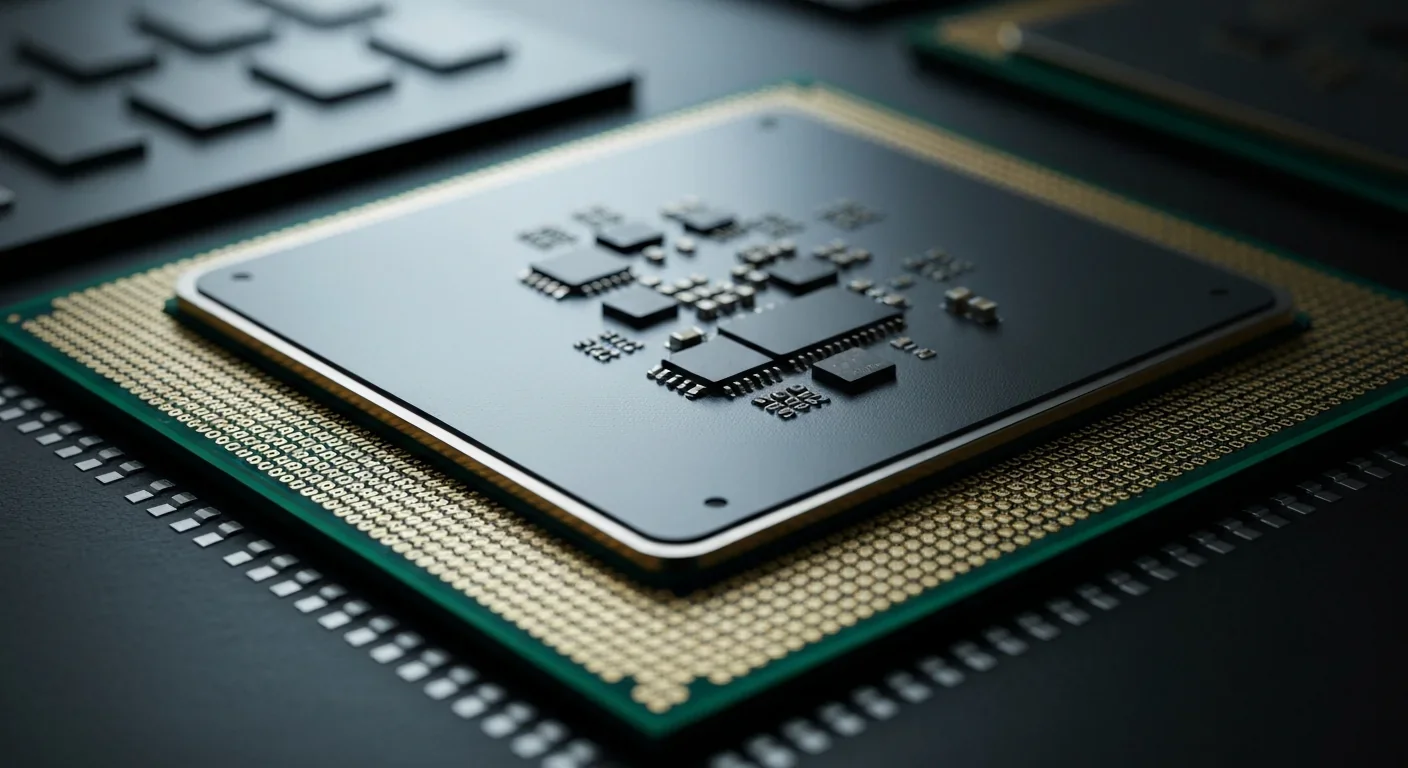

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.