Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: Scientists have discovered that controlled cellular stress in mitochondria activates protective responses that extend lifespan in model organisms. This mitochondrial unfolded protein response may explain why exercise, fasting, and other longevity interventions work at the molecular level.

What if the secret to a longer life isn't avoiding stress, but experiencing just the right amount of it? In labs around the world, researchers are uncovering evidence that controlled cellular stress - particularly inside the tiny powerhouses called mitochondria - might unlock unprecedented insights into human longevity. This revelation flips conventional thinking about aging on its head and suggests that what doesn't kill your cells might actually make them stronger.

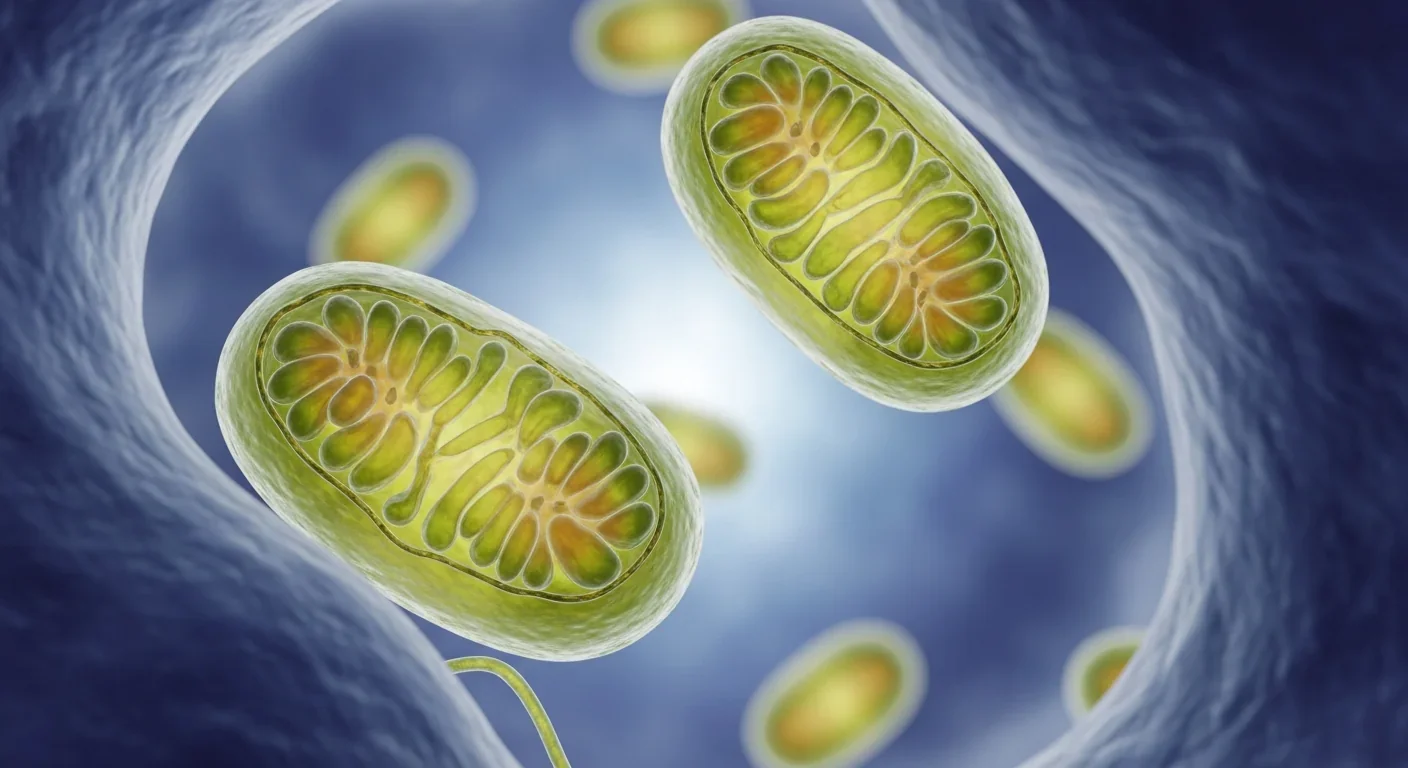

Inside every one of your cells are hundreds of mitochondria, working around the clock to generate the energy that keeps you alive. These ancient organelles, descendants of bacteria that merged with our ancestors billions of years ago, maintain their own genetic code and protein-manufacturing machinery. But when something goes wrong - when proteins misfold inside these cellular batteries - mitochondria don't suffer in silence.

They activate what scientists call the mitochondrial unfolded protein response, or UPRmt for short. Think of it as an emergency broadcast system that sends distress signals from the mitochondria to the cell's nucleus, triggering a coordinated protective response across the entire cell. This isn't just damage control - it's an sophisticated communication network that's captured the attention of longevity researchers worldwide.

The UPRmt pathway involves several key molecular players. When misfolded proteins accumulate in mitochondria, specialized chaperone proteins like HSP60 try to refold them correctly. If the problem overwhelms these quality control mechanisms, proteases like ClpP break down the damaged proteins. Meanwhile, signaling molecules shuttle between the mitochondria and nucleus, activating genes that produce more chaperones, antioxidants, and protective factors.

Mitochondria can't fix major issues alone because most mitochondrial proteins are encoded in nuclear DNA, not in the mitochondria's own genome. The UPRmt bridges this communication gap.

This retrograde signaling - communication flowing backward from organelles to the nucleus - represents one of biology's elegant solutions to a fundamental problem. Mitochondria can't fix major issues alone because most mitochondrial proteins are actually encoded in nuclear DNA, not the mitochondria's own genome. The UPRmt bridges this gap, coordinating a cell-wide response to mitochondrial stress.

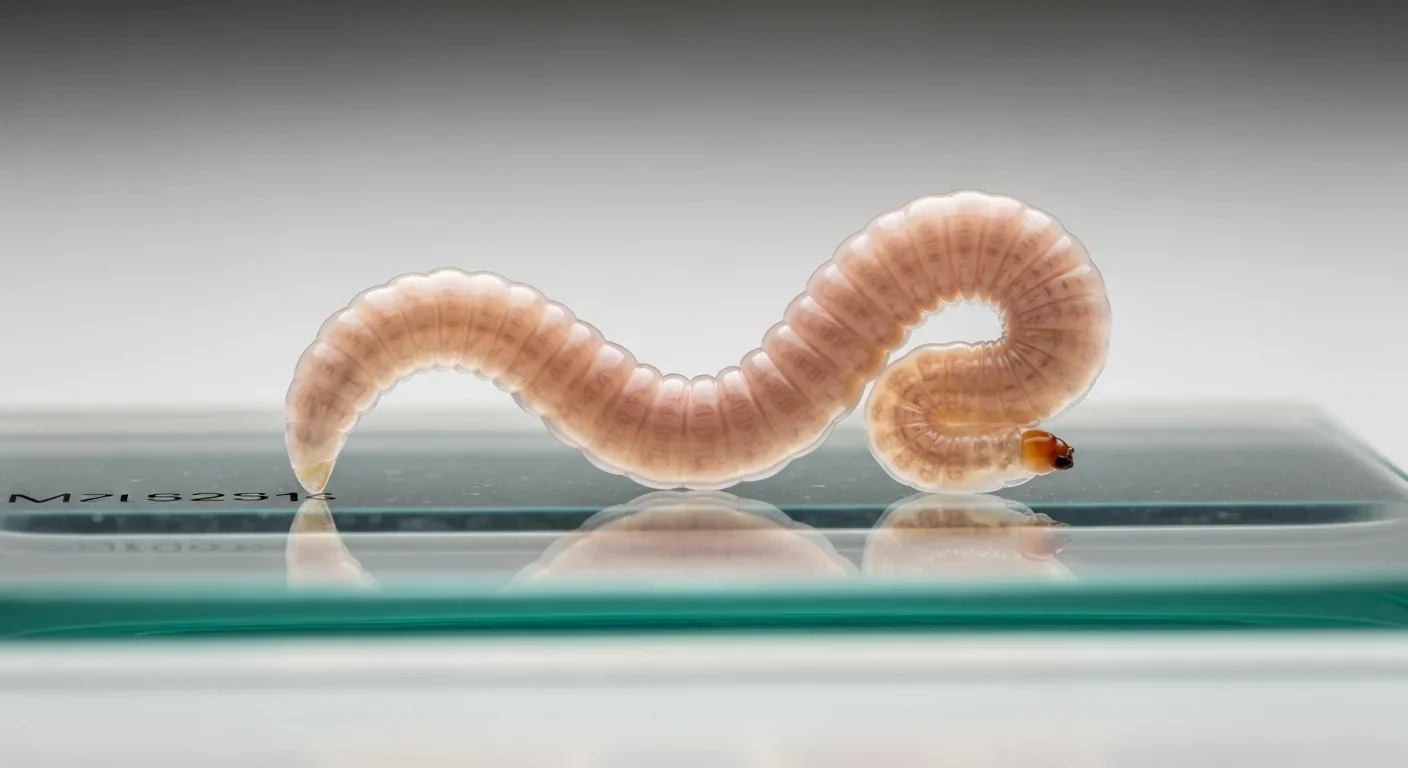

The breakthrough came from an unlikely source: tiny transparent worms called Caenorhabditis elegans. These millimeter-long nematodes have become biology's workhorses because scientists can manipulate their genes with precision and watch entire lifespans unfold in just two weeks.

Research using C. elegans has demonstrated that activating the UPRmt doesn't just help cells cope with stress - it actually extends lifespan. When researchers used genetic tricks or chemical compounds like doxycycline to induce mild mitochondrial stress, worms lived significantly longer than their unstressed counterparts. Even more remarkably, this lifespan extension was associated with transcriptomic changes indicating a coordinated stress response across multiple biological systems.

Scientists could visualize this process in real-time by engineering worms with fluorescent reporters. One popular marker, hsp-6p::gfp, glows green when the UPRmt activates, allowing researchers to literally see the stress response lighting up inside living organisms. These experiments revealed that genetic variations affecting both lifespan and UPRmt activation often mapped to the same chromosomal regions, suggesting the two processes are intimately connected.

But the story doesn't end with worms. Similar longevity effects from mitochondrial stress have been observed in fruit flies, mice, and other model organisms. The consistency across evolutionarily distant species suggests that the UPRmt-longevity connection reflects something fundamental about how multicellular life deals with aging.

This phenomenon belongs to a broader biological principle called hormesis - the idea that low doses of stress can be beneficial, even when higher doses are harmful. The concept of hormesis applies to everything from exercise (which damages muscle fibers that grow back stronger) to radiation (where tiny exposures may activate DNA repair mechanisms).

Mitohormesis specifically refers to hormetic effects triggered by mitochondrial stress. The logic is evolutionary: organisms that could sense early warning signs of mitochondrial trouble and mount preemptive defenses would have survival advantages. Over millions of years, natural selection refined these systems, creating the finely tuned stress response pathways we're now discovering.

"The hormesis principle reveals that moderate stress triggers a disproportionately large protective response - creating the biological equivalent of vaccines for cellular aging."

- Longevity Research Findings

The hormesis principle helps explain why many longevity interventions work. Caloric restriction, for instance, creates a mild metabolic stress that activates protective pathways including the UPRmt. Exercise generates reactive oxygen species in mitochondria, triggering adaptations that ultimately improve mitochondrial function. Even some pharmaceutical interventions like metformin appear to work partly by inducing mild mitochondrial stress.

Research has identified specific dose-response curves for mitohormetic effects. Too little stress provides no benefit. Too much causes actual damage. But there's a sweet spot - a Goldilocks zone - where the stress level is "just right" to trigger adaptive responses without overwhelming cellular defenses. Finding and maintaining that zone represents both the promise and the challenge of translating UPRmt research into practical interventions.

Understanding how the UPRmt works at a molecular level reveals just how sophisticated this system is. The process begins when mitochondrial protein homeostasis - what biologists call proteostasis - becomes disrupted. This can happen through various mechanisms: mutations in mitochondrial DNA, exposure to toxins, aging-related decline in quality control, or deliberate interventions like those used in research.

The initial sensors include various mitochondrial proteases and chaperones that detect accumulating misfolded proteins. When these guardians become overwhelmed, they trigger signaling cascades that reach the nucleus. In C. elegans, this involves transcription factors like ATFS-1, which shuttles between mitochondria and nucleus depending on mitochondrial health. When mitochondrial import is impaired by stress, ATFS-1 accumulates in the nucleus where it activates stress response genes.

In mammals, the system is more complex and less completely understood. Multiple pathways contribute to mitochondrial stress signaling, including the integrated stress response (ISR) involving kinases like GCN2, and transcription factors like ATF4 and ATF5. These pathways converge on programs that upregulate mitochondrial chaperones, enhance mitochondrial biogenesis, promote autophagy of damaged mitochondria, and boost antioxidant defenses.

The UPRmt also communicates with other cellular stress response systems, creating an integrated defense network. It intersects with the unfolded protein response in the endoplasmic reticulum (another organelle where proteins are processed), metabolic stress responses, and immune signaling pathways. This crosstalk allows cells to coordinate responses across multiple systems when facing complex challenges.

Recent research has revealed that sites of contact between mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum - called MERCs (mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum contacts) - may serve as regulatory hubs for the UPRmt. These physical bridges between organelles facilitate communication and coordinate stress responses, adding another layer of sophistication to cellular stress management.

One of the most exciting aspects of UPRmt research is how it connects the dots between seemingly different longevity interventions. Scientists have known for decades that certain practices and compounds extend lifespan in model organisms, but the mechanisms often remained mysterious. The UPRmt provides a unifying framework that explains many of these effects.

Caloric restriction, the most reliably documented longevity intervention across species, creates a metabolic state that mildly stresses mitochondria. This stress activates the UPRmt and related pathways, preparing cells to deal with future challenges. The result is organisms that live longer and remain healthier deeper into their lifespans - a phenomenon scientists call extended healthspan.

Exercise works through similar mechanisms. When you work out, your muscles' mitochondria work harder, generating both energy and reactive oxygen species. This controlled stress triggers adaptive responses including UPRmt activation, leading to increased mitochondrial biogenesis (creation of new mitochondria) and improved mitochondrial function. The immediate stress of exercise translates into long-term resilience.

Caloric restriction, exercise, and metformin all work through a common mechanism: inducing mild mitochondrial stress that activates protective UPRmt pathways, explaining decades of longevity research through a unified framework.

Metformin, a diabetes drug that's attracted attention as a potential anti-aging compound, appears to work partly by inhibiting complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. This mild inhibition creates the kind of controlled stress that activates protective responses including the UPRmt. Other compounds under investigation for longevity effects - including rapamycin, NAD+ precursors, and various natural products - may similarly work through mitohormetic mechanisms.

NAD+ supplementation with compounds like NMN has shown promise in enhancing mitochondrial stress responses while improving cognition in animal models. This makes sense because NAD+ is crucial for mitochondrial function, and boosting its levels may help cells mount more effective stress responses.

Even dietary choices beyond caloric restriction may influence mitohormesis. Certain plant compounds called phytochemicals - found in foods like cruciferous vegetables, berries, and green tea - can induce mild mitochondrial stress that activates protective pathways. This helps explain why diets rich in these foods are associated with better health outcomes and potentially longer lifespans.

The connection between UPRmt and longevity has profound implications for treating age-related diseases. Many conditions associated with aging - including neurodegenerative diseases, heart disease, metabolic disorders, and immune dysfunction - involve mitochondrial problems. If declining mitochondrial quality is a root cause of aging-related pathology, interventions that boost the UPRmt might address multiple diseases simultaneously.

Neurodegenerative diseases provide a compelling example. Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's disease all involve disrupted mitochondrial proteostasis and accumulation of misfolded proteins. The brain's high energy demands make neurons particularly vulnerable to mitochondrial dysfunction. Strategies that enhance the UPRmt might help neurons cope with protein aggregation and maintain function despite aging-related stress.

Heart disease represents another major target. As hearts age, they experience mitochondrial, endoplasmic reticulum, and metabolic stress that impairs cardiac function. The UPRmt normally helps heart cells adapt to increased workload and metabolic demands, but this capacity declines with age. Restoring robust UPRmt function might help aging hearts maintain their resilience.

Research has demonstrated that certain traditional medicine formulations can activate the UPRmt through PI3K/Akt signaling pathways, providing neuroprotection in stroke models. This suggests that pharmaceutical targeting of UPRmt activation could become a viable therapeutic strategy.

The immune system also relies on mitochondrial health. Recent work has shown that the UPRmt plays protective roles in regulatory T cell function during immune aging. This connection could explain why mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to age-related immune decline and suggests that UPRmt-targeted interventions might help maintain immune health in older individuals.

Metabolic diseases including diabetes and metabolic syndrome involve mitochondrial dysfunction. Dysfunctional mitochondria trigger retrograde signaling that impairs pancreatic β-cells, contributing to diabetes development. Conversely, interventions that improve mitochondrial stress responses might help prevent or treat these conditions.

The UPRmt's role in cancer presents a more complicated picture. On one hand, cancer cells often have altered mitochondrial metabolism and may depend on stress response pathways like the UPRmt to survive in harsh tumor environments. Targeting mitochondrial proteases like ClpP has emerged as a potential cancer therapy, with ClpP agonists showing promise in preclinical studies.

The idea is to overwhelm cancer cells with excessive mitochondrial stress they can't handle, driving them toward death while normal cells tolerate the intervention. However, this approach requires careful calibration because the same pathways that promote cancer cell survival under stress also protect normal cells from damage.

Some cancer therapies might work partly by inducing mitohormesis in normal tissues, helping them withstand treatment-related stress. Understanding these dynamics better could lead to combination therapies that simultaneously stress cancer cells beyond their coping capacity while protecting normal tissues through controlled hormetic activation.

Despite rapid progress, many fundamental questions about the UPRmt remain unanswered. Scientists are still working out the complete molecular details of how mitochondrial stress signals reach the nucleus, particularly in mammalian cells where the pathways appear more complex than in simpler organisms.

The field is actively investigating how different types of mitochondrial stress - proteotoxic stress versus oxidative stress versus bioenergetic stress - trigger distinct or overlapping responses. There's evidence that the UPRmt can act both locally (within the stressed cell) and systemically (affecting distant tissues), but the mechanisms and implications of this long-range signaling remain poorly understood.

Research on retrograde mitochondrial signaling is revealing that these pathways govern not just stress responses but also tissue identity and maturity. This suggests the UPRmt and related systems play roles in development and tissue maintenance beyond their stress response functions.

"A critical question remains: will the lifespan extensions observed in worms and flies translate to humans aging over decades in complex real-world environments?"

- Aging Research Community

A critical unresolved question is whether the relationships observed in model organisms will translate to humans. While mice, flies, and worms share core UPRmt machinery with us, human aging occurs over decades in complex environmental and genetic contexts that lab models can't fully capture. Lifespan extension in C. elegans might not predict the same effects in humans.

There's also debate about whether activating the UPRmt is always beneficial. Some research suggests that chronic, excessive activation might have downsides, and that timing and context matter enormously. The goal isn't to keep stress responses permanently activated but to maintain the capacity to mount them effectively when needed.

So what does all this mean for someone interested in healthy aging? While we're years away from UPRmt-targeted drugs, the research suggests that many existing lifestyle interventions may work partly through mitohormesis.

Regular exercise remains one of the most reliable ways to induce beneficial mitochondrial stress. Both endurance exercise and resistance training stress mitochondria in ways that trigger adaptive responses. The key is consistency and appropriate intensity - enough to challenge your system without overwhelming it.

Dietary approaches including mild caloric restriction, intermittent fasting, or time-restricted eating create metabolic conditions that may activate mitohormesis. You don't need to starve yourself; even modest reductions in caloric intake or extending overnight fasting periods might provide benefits through these mechanisms.

Certain dietary compounds including sulforaphane (from broccoli), resveratrol (from grapes), and various polyphenols may induce mild mitochondrial stress that activates protective responses. While supplement industry claims often outpace evidence, there's mechanistic support for phytochemicals acting through hormetic pathways.

Temperature stress - through practices like sauna use or cold exposure - might also work partly through mitohormesis. Heat shock and cold shock proteins overlap with mitochondrial stress response pathways, suggesting these practices could provide additive benefits.

The hormesis principle suggests that constant comfort might be detrimental for longevity. Regular, controlled challenges - through exercise, fasting, and temperature variation - keep cellular stress response systems tuned and ready.

The common thread is controlled, intermittent stress followed by recovery periods. The hormesis principle suggests that constant comfort might actually be detrimental, while regular challenges keep cellular stress response systems tuned and ready.

Stepping back, the UPRmt story reveals something profound about aging itself. For decades, scientists debated whether aging is programmed or simply accumulated damage. The UPRmt suggests a middle ground: aging reflects the gradual decline of evolved maintenance and repair systems.

Organisms evolved sophisticated stress response pathways because stress is inevitable. These systems work beautifully in young organisms but gradually lose effectiveness with age. The mitochondrial theory of aging has evolved from simple ideas about oxidative damage to nuanced understanding of how mitochondrial dysfunction causes or contributes to physiologic aging through impaired stress signaling.

Evolutionary theory helps explain why these systems decline. Natural selection optimizes organisms for reproduction, not indefinite lifespan. Once you've passed on your genes, selection pressure for maintaining cellular function drops off. The UPRmt and related pathways evolved to get organisms through reproductive years, not to maintain them indefinitely.

But understanding these systems opens possibilities for intervention. If we can understand what declines and why, we might be able to restore or enhance these functions, extending not just lifespan but healthspan - the years of vigorous, disease-free life.

The research connecting cellular stress responses to longevity is reshaping how we think about aging. Rather than an inevitable decline, aging appears increasingly as a process influenced by how effectively our cells maintain proteostasis, respond to stress, and coordinate protective responses across organ systems. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response sits at the heart of this maintenance system, connecting cellular power generation to longevity in ways we're only beginning to understand.

The next decade will likely bring significant advances in translating UPRmt research into practical interventions. Researchers are actively searching for compounds that can safely activate the pathway without excessive side effects. Clinical trials may test whether enhancing mitochondrial stress responses can slow age-related diseases in humans.

We're also likely to see more personalized approaches. Genetic variations affect how individuals respond to mitochondrial stress, suggesting that optimal interventions might vary between people. As genetic testing becomes cheaper and our understanding deepens, we might develop personalized protocols for activating beneficial stress responses based on individual genetic and metabolic profiles.

Emerging technologies for monitoring mitochondrial health in real-time could eventually allow people to track their mitochondrial stress responses and adjust their lifestyle interventions accordingly. Imagine a future where wearable devices don't just count steps but assess cellular stress levels and provide recommendations for optimizing mitohormesis.

The intersection of aging research, mitochondrial biology, and stress response pathways represents one of the most exciting frontiers in biomedicine. What started with glowing worms and basic questions about cellular stress has evolved into a sophisticated understanding of how life maintains itself against entropy. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response - once just an obscure cellular pathway - may hold keys to healthier, longer lives.

The stress signals emanating from your mitochondria right now aren't just background noise. They're ancient conversations between organelles and nuclei, refined over billions of years, coordinating your cells' responses to the challenges of staying alive. Understanding and harnessing these conversations might be our best strategy for pushing back against the limits of human lifespan, one stressed mitochondrion at a time.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.