The Ancient Protein Clock That Ticks Without DNA

TL;DR: Ten minutes in nature measurably lowers cortisol, reduces heart rate, and shifts your nervous system toward rest. The biophilia effect isn't mystical - it's quantifiable physiology, and doctors are now prescribing park time alongside medication.

Within the next five years, your doctor might write you a prescription to spend 20 minutes in your local park. This isn't science fiction - it's already happening across dozens of cities, and the data explaining why is transforming how we think about human health. Just as we discovered that exercise isn't optional luxury but biological necessity, researchers are now quantifying what our ancestors always knew: nature isn't just pleasant background scenery. It's medicine, and we're finally learning the dosage.

Something remarkable happens when humans step into green space, and it's not just in our heads. Recent meta-analyses tracking thousands of participants have documented measurable, repeatable changes in stress physiology within minutes of nature exposure. We're talking about drops in cortisol levels, reduced heart rate, lowered blood pressure, and shifts in autonomic nervous system function that you can literally measure with a blood test or heart monitor.

The minimum effective dose? Ten minutes. That's less time than your average coffee break, yet studies show it's enough to produce "significant and beneficial impact" on mental health markers among college students. But here's what makes this different from previous feel-good claims about nature: researchers aren't just measuring how people say they feel. They're tracking biomarkers - cortisol in saliva samples, heart rate variability on monitors, blood pressure readings that insurance companies actually care about.

One particularly striking study found that middle-aged men with hypertension who simply viewed forest landscapes for ten minutes showed measurable drops in heart rate. They weren't hiking or meditating - just looking at trees. The implications ripple outward from there: if visual exposure alone triggers physiological relaxation, what does that mean for office design? For hospital recovery rooms? For urban planning?

The biophilia hypothesis, first popularized by biologist E.O. Wilson, proposed that humans have an innate tendency to seek connections with nature and other forms of life. For decades, this remained an elegant theory. Now it's becoming documented fact, backed by neuroimaging studies and stress hormone assays.

Modern research shows that when we're surrounded by concrete and screens, our sympathetic nervous system - the fight-or-flight mechanism - stays partially activated. It's like running software in the background that slowly drains your battery. Nature exposure appears to flip the switch, activating the parasympathetic system that governs rest and recovery. Your body literally shifts gears.

This isn't about romanticizing a return to pre-industrial life. It's about recognizing that our biology evolved over millions of years in natural environments, while we've spent less than two centuries creating almost entirely artificial surroundings. The mismatch creates measurable stress, and the solution isn't to abandon cities - it's to bring nature into them.

Think about the last time you felt genuinely relaxed. Chances are, natural elements played a role, even if you didn't notice. The sound of water, the sight of greenery through a window, the texture of wood under your hands. These aren't random preferences. They're signals your nervous system recognizes as safety cues, telling your stress response to stand down.

When researchers track what actually happens inside the body during nature exposure, the mechanisms become clear. Cortisol levels drop - cortisol being the primary stress hormone your body releases when the sympathetic nervous system kicks in. Heart rate variability increases, which sounds technical until you understand it measures your body's ability to flexibly respond to stress. Higher variability means better stress management capacity.

Blood pressure falls. Immune markers improve, including natural killer cell activity - the cells that defend against viruses and tumors. Some researchers attribute this partly to phytoncides, airborne chemicals that plants emit to protect themselves from insects and decay. When you breathe forest air, you're inhaling these compounds, and your immune system apparently likes them.

The autonomic nervous system changes are particularly fascinating because they're involuntary - you can't fake them or placebo-effect your way into them. When researchers compared people exercising in natural versus urban environments, the nature group showed lower salivary cortisol levels after the same intensity workout. Same exercise, same effort, different biological response depending on the surroundings.

Even viewing photographs of green landscapes produces measurable stress reduction compared to images of built environments. Your brain recognizes the difference at a level deeper than conscious thought, triggering cascades of neurochemical and hormonal shifts that ripple through your entire system.

Green isn't the only color that matters. The Blue Health project, surveying 18,000 people across 18 European countries, discovered something unexpected: proximity to water - oceans, rivers, lakes - correlates even more strongly with mental well-being than distance to parks alone.

There's something about water that hits different. Maybe it's the negative ions in sea spray, the rhythmic sound of waves, or simply that water features required our ancestors to settle nearby for survival. Whatever the mechanism, people consistently report feeling better near waterways, and the data backs up their subjective experience.

This matters for urban planning. Cities can't always preserve vast forests, but they can protect riverfronts, create artificial lakes, install fountains. The evidence suggests these investments pay dividends in public health that might offset healthcare costs down the line. Singapore has already figured this out, designing a "city in a garden" where 47% of the island is green or blue space despite being one of the world's most densely populated places.

Not everyone can access wilderness, and that's where the science gets creative. Researchers have found that indoor plants improve not just air quality but empathy, compassion, and relationship quality among people who spend time around them. It sounds too simple to be true, yet controlled studies keep confirming it.

Office environments with plants and natural light show reduced sick days and higher productivity. One study at the University of Exeter found that enriching previously sparse offices with plants increased productivity by 15% while improving well-being and concentration. The plants weren't decorative - they were functional equipment for human performance.

Virtual reality nature environments are showing promise too. For people with mobility limitations, chronic illness, or those in urban areas lacking green access, VR nature experiences can deliver some of the same stress-reducing benefits. It's not identical to being outdoors, but it's vastly better than staring at blank walls, and for some populations it may be the most accessible option.

Even nature sounds and imagery make a difference. Apps that play forest sounds or flowing water aren't just helping you ignore noisy neighbors - they're providing acoustic cues that shift your nervous system toward relaxation. Desktop backgrounds of natural scenes, windows with views of greenery, wooden textures in furniture - these aren't frivolous aesthetic choices. They're interventions.

Forward-thinking companies are already acting on this data. WeWork has integrated biophilic design principles - incorporating natural elements - across their spaces, not for branding but because the business case is solid. Lower stress means fewer sick days, better focus, higher retention.

Google's offices famously include extensive green space and natural materials. Amazon's Seattle headquarters contains climate-controlled spheres filled with 40,000 plants from around the world - not as a gimmick, but as workspace where employees report higher satisfaction and creativity. These aren't perks for engineers who might leave for competitors. They're infrastructure investments in human performance.

The healthcare sector is particularly interested. Some hospitals are installing green spaces visible from patient rooms after studies showed faster recovery times and reduced pain medication use among patients with nature views. Surgery patients with windows overlooking trees had shorter hospital stays than those facing brick walls. The effect size was significant enough that architects now consider it in hospital design.

The most radical shift is happening in medicine itself. Park prescription programs - where doctors literally write prescriptions for time in nature instead of, or alongside, pharmaceutical interventions - have launched in over 30 U.S. states. DC, for instance, has ParkRx, connecting patients with local green spaces tailored to their mobility and interests.

These aren't alternative medicine fantasies. They're evidence-based interventions targeting conditions where stress plays a major role: hypertension, anxiety, depression, chronic pain. One meta-analysis examining nature exposure dose effects found that regular time outdoors produced clinically meaningful improvements in adults with mental illness - improvements comparable to medication for some conditions, with zero side effects beyond maybe mosquito bites.

The UK has gone even further, with the National Health Service supporting social prescribing that includes nature-based interventions as standard care options. When the cost of mental health crises keeps rising and medication adherence remains spotty, telling someone to walk in a park three times a week for 20 minutes sounds almost too simple. But if it works - and the data increasingly says it does - simplicity becomes a feature, not a bug.

The dose-response relationship is becoming clearer. Ten minutes produces measurable benefit. Twenty to thirty minutes seems optimal for significant cortisol reduction and mood improvement. Two hours per week - the amount recommended by some researchers - correlates with substantial improvements in self-reported health and well-being.

You don't need wilderness. Urban parks deliver many of the same benefits as forests, though forest bathing - the Japanese practice of shinrin-yoku - appears to offer additional advantages, possibly due to higher concentrations of phytoncides and greater biodiversity. Even a tree-lined street provides more benefit than concrete alone.

The activity matters less than you'd think. Walking helps, but so does sitting on a bench. Reading under a tree. Eating lunch in a park. The key variable is presence in the environment, not intensity of physical activity, though combining both amplifies benefits.

Consistency beats duration. Fifteen minutes daily appears more beneficial than two hours once a week, suggesting that regular exposure helps maintain baseline stress regulation rather than just providing temporary relief. Think of it like sleep - you can't sleep for 14 hours on Sunday and skip it the rest of the week. Your nervous system needs regular nature contact to stay calibrated.

Wearable technology is opening new frontiers. Imagine a smartwatch that doesn't just count steps but monitors your heart rate variability and cortisol proxies, notifying you when your stress markers creep up and suggesting the nearest green space. Research teams are already developing algorithms to optimize nature prescriptions based on individual biomarker responses.

Some people respond more strongly to forests, others to water. Some need visual stimuli, others benefit more from soundscapes. As data accumulates, we'll be able to personalize recommendations the way we're starting to personalize nutrition - not based on general guidelines but on your specific physiology.

The policy implications are profound. If nature exposure prevents stress-related illness at scale, then urban green space isn't a luxury amenity - it's public health infrastructure as essential as clean water. Cities that preserve and expand parks aren't just making residents happier; they're reducing long-term healthcare costs and productivity losses from stress-related conditions.

Japan's forest bathing tradition has gone mainstream, but it originated from a specific cultural relationship with nature embedded in Shinto beliefs. Shinrin-yoku became official policy in the 1980s, with the government designating Forest Therapy Roads and funding research into the physiological mechanisms.

Nordic countries approach this differently, with friluftsliv - a philosophy of outdoor life - woven into educational systems. Norwegian children spend substantial time outdoors regardless of weather, normalizing nature contact from an early age. The evidence suggests this creates baseline resilience against stress-related disorders later in life.

Indigenous cultures worldwide have maintained continuous traditions of nature connection that Western science is only now validating. Australian Aboriginal songlines, Native American land relationships, and countless other traditions encoded this knowledge long before we had cortisol assays. The current research isn't discovering something new - it's translating ancient wisdom into the language of biomarkers and randomized controlled trials.

Start ridiculously small. If you work in an office, position your desk near a window with a nature view if possible. If that's not an option, a desktop background of a natural scene provides measurable benefit. Add a plant to your workspace - something low-maintenance like a pothos or snake plant that'll survive your benign neglect.

Schedule a daily 15-minute park visit the way you'd schedule a meeting. Put it in your calendar. Treat it as non-negotiable. The data suggests this small habit delivers returns that justify the time investment multiple times over through improved focus, reduced sick days, and better sleep.

If you have kids, prioritize outdoor time over structured activities. The research on attention restoration shows that natural environments replenish depleted cognitive resources in ways that indoor activities simply don't match. That park trip isn't stealing time from homework - it's creating the mental conditions that make homework more effective.

For those with limited mobility or access, explore virtual nature experiences. VR headsets are becoming affordable, and platforms are emerging specifically for therapeutic nature immersion. Even a YouTube video of a forest walk with good headphones provides some benefit, though the immersive experience appears more effective.

The evidence is mounting that we've designed living environments that chronically activate our stress response, then tried to manage the consequences with medication and therapy while ignoring the simplest intervention: changing the environment itself. That's starting to shift.

Expect building codes to evolve, incorporating minimum natural light requirements and biophilic design standards. Green exercise - physical activity in natural settings - will likely become a standard part of rehabilitation protocols for everything from cardiac events to mental health crises.

Insurance companies, always following the data, may start offering premium reductions for members who log regular park visits, the same way some discount gym memberships now. Sounds intrusive until you remember they already track step counts and reward pharmacy compliance. If nature exposure reduces claims, they'll incentivize it.

The ultimate goal isn't to make everyone move to rural areas - that's neither practical nor necessary. It's to recognize that the environments we inhabit shape our biology in measurable ways, and we now have the data to design those environments intentionally. Every new building, every renovated park, every urban planning decision becomes an opportunity to either support human stress physiology or undermine it.

Your body is running software written in a natural environment. When you deprive it of those inputs, stress systems misfire. When you provide them - even in small doses, even virtually - measurable improvements cascade through multiple systems. This isn't mysticism or wellness culture fluff. It's documented, replicable, quantifiable physiology.

Ten minutes. That's less time than you'll spend reading this article. But if you spend those ten minutes in a park or under a tree instead of at your desk, you're not just taking a break - you're delivering a therapeutic intervention to your nervous system that research confirms lowers cortisol, reduces blood pressure, and improves markers that predict long-term health outcomes.

The prescription is simple: go outside. Look at trees. Listen to water. Touch grass, literally. Your distant ancestors spent their entire lives doing this without thinking about it. You have to schedule it, but the payoff - a nervous system that remembers how to rest - makes it the most effective intervention that costs nothing and requires no prescription.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

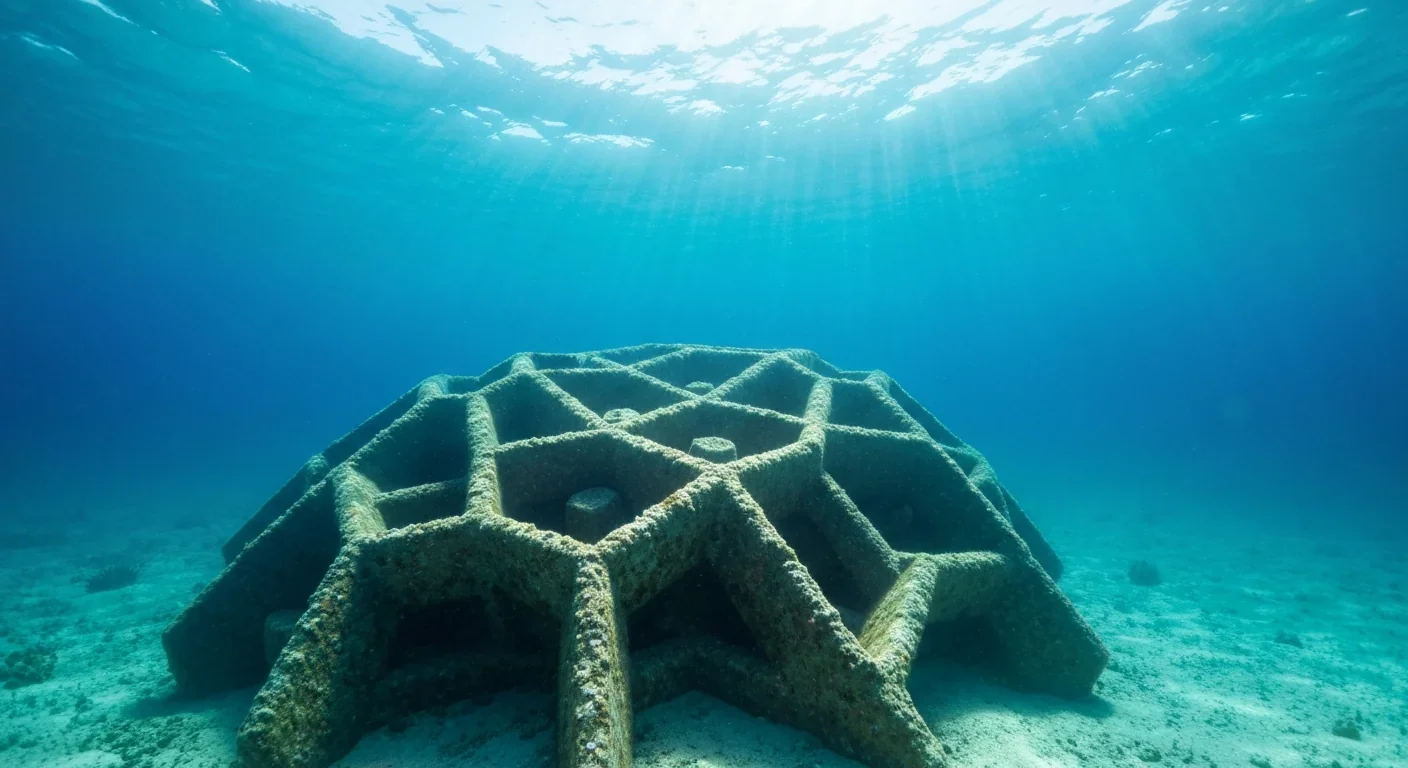

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

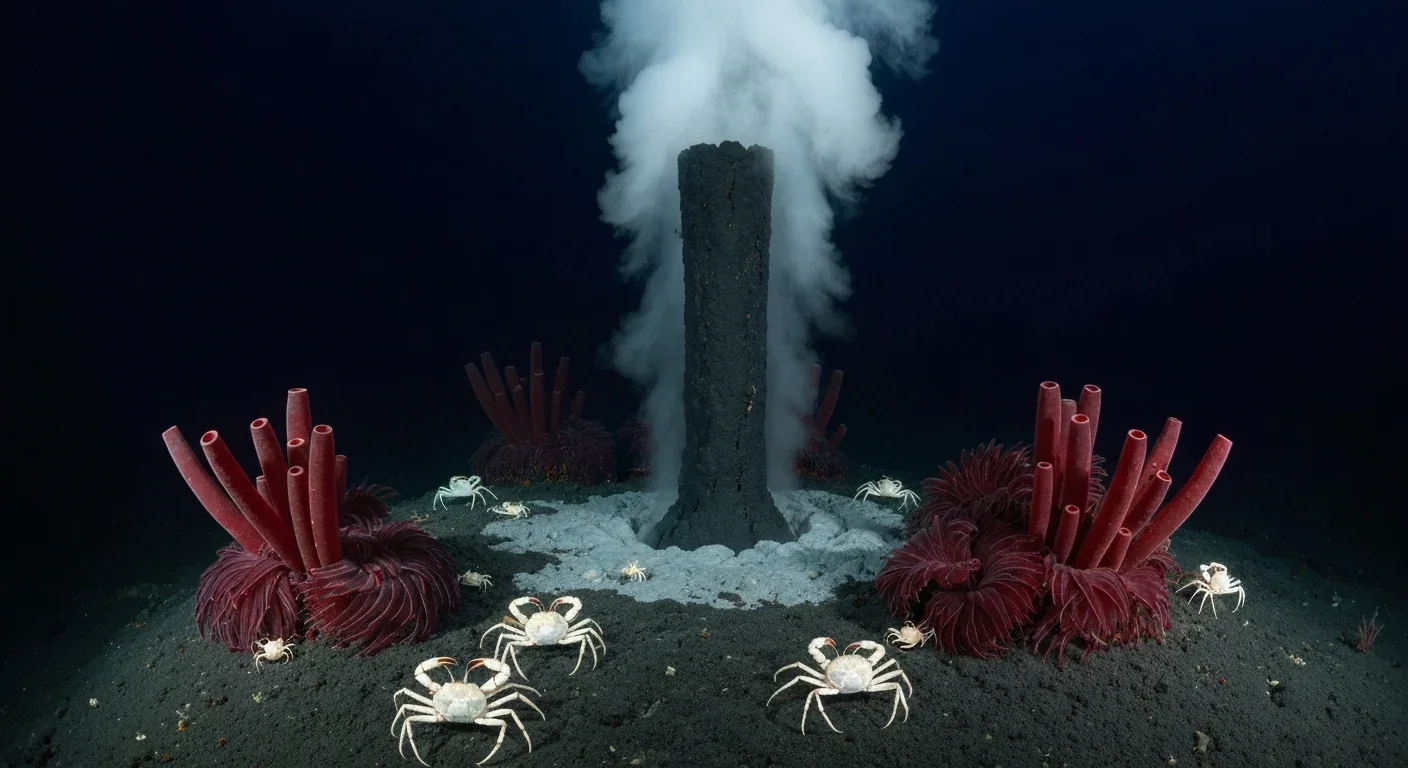

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

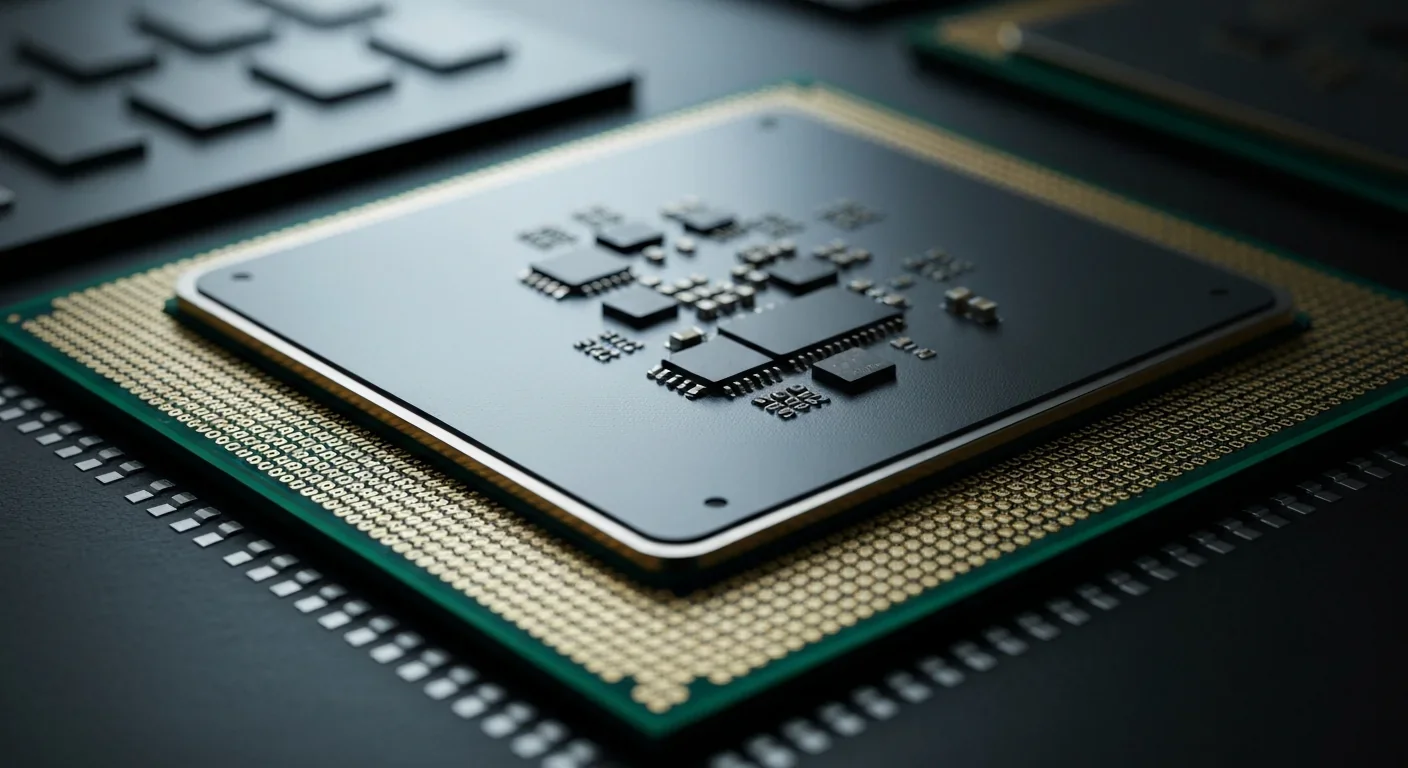

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.