Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: Optogenetic therapy is restoring vision to blind patients by engineering surviving retinal cells to become light-sensitive, bypassing dead photoreceptors. Recent clinical trials show patients with retinitis pigmentosa gaining functional vision after a single injection, enabling them to navigate spaces and locate objects for the first time in years.

The fundamental problem in degenerative blindness is simple but devastating: the eye's photoreceptors - rods and cones that detect light - die off progressively. Once they're gone, traditional medicine has had nothing to offer. Glasses can't help if there's no signal reaching the brain. But optogenetic therapy flips the script entirely by engineering other retinal cells to become light-sensitive.

Here's how it works: researchers deliver a gene that codes for light-sensitive proteins - called opsins - into surviving retinal cells that normally don't respond to light at all. These proteins, originally discovered in algae, act like molecular light switches. When light hits them, they trigger electrical signals that travel to the brain, effectively bypassing the dead photoreceptors and restoring a functional visual pathway.

The most advanced trial, called PIONEER, targets retinal ganglion cells in patients with end-stage retinitis pigmentosa who have been legally blind for years. After a single injection into the eye containing a viral vector with the ChrimsonR opsin gene, patients wear specialized amber-light goggles that stimulate these newly light-sensitive cells. The results? Patients who couldn't see anything began locating objects, counting items on a table, and navigating obstacles.

Let's be clear about what "restored vision" actually means here. This isn't 20/20 sight. Patients aren't reading fine print or recognizing faces. But for someone who's been blind, even rudimentary vision is life-changing. In clinical trials, the improvements are measured in functional abilities: Can you locate a white stripe on a crosswalk? Can you navigate around furniture without bumping into it? Can you tell if a light is on or off?

Dr. Joseph Martel from the University of Pittsburgh, who leads the PIONEER trial, puts it plainly: "This is not a natural type of vision." It's artificial, grainy, and requires extensive training. Patients must learn to interpret what they're seeing because the visual information is fundamentally different from natural sight. But here's what matters: in the RESTORE trial of MCO-010, a similar optogenetic therapy, patients showed statistically significant improvement in best-corrected visual acuity - an average improvement of 0.382 LogMAR in the low-dose group and 0.539 LogMAR in the high-dose group at 76 weeks. That translates to the difference between seeing nothing and seeing enough to gain independence.

In the RESTORE trial, patients with advanced retinitis pigmentosa showed measurable vision improvement at 52 weeks, with continued benefit at 76 weeks - indicating durable effects from a single injection.

The PRIMA implant system, which uses a photovoltaic sub-retinal device rather than gene therapy but serves a similar function, demonstrated that patients gained what's called "form vision" - the ability to read large letters, write, and recognize symbols. That might sound modest, but for someone who's been blind, it's the difference between total dependence and functional autonomy.

The delivery mechanism is surprisingly straightforward: a single intravitreal injection - meaning a needle inserted into the vitreous gel of the eye - delivers billions of viral vectors carrying the opsin gene. The vectors, typically adeno-associated viruses (AAV), are specially engineered to be harmless carriers that infect the target cells without causing disease.

The choice of which cells to target matters enormously. The MCO-010 therapy targets bipolar cells, which sit in the middle layer of the retina. The PIONEER trial targets retinal ganglion cells, which are the final output neurons sending signals to the brain. Both strategies work because these cells survive even after photoreceptors die - they just need to be re-engineered to respond to light.

What makes optogenetics particularly clever is its use of specific opsins matched to particular light wavelengths. ChrimsonR, for example, responds to amber light around 590-600 nanometers. That's why patients wear amber-tinted goggles with built-in cameras and light projectors. The camera captures the visual scene, and the goggles translate it into pulses of amber light that activate the engineered cells. It's a hybrid system: biological and electronic working together.

Not everyone with vision loss qualifies. The fundamental requirement is that the target cells must still be alive. For retinitis pigmentosa patients, that means the inner retinal layers - bipolar and ganglion cells - need to be intact even though the photoreceptors are gone. For age-related macular degeneration, the situation is more complex; dry AMD patients with geographic atrophy may benefit, but only if sufficient retinal cells remain.

The RESTORE trial enrolled patients with severe vision loss - 20/400 or worse - due to advanced retinitis pigmentosa. That's legally blind by any standard. What's revolutionary about MCO-010 is that it's mutation-agnostic. Traditional gene therapy for RP requires knowing exactly which genetic mutation caused the disease so you can replace that specific broken gene. But optogenetics doesn't care what caused the photoreceptors to die; it simply engineers different cells to take over their function. This means a single therapy could potentially treat thousands of different genetic mutations that all lead to the same endpoint: dead photoreceptors.

"MCO-010 represents the first evidence of effectiveness of a mutation-agnostic gene therapy for a genetic disease."

- Nanoscope Therapeutics Research Team

Timing matters too. Research in animal models shows that gene therapy works best when there's still a critical mass of target cells remaining. One study found that dogs treated when more than 63% of photoreceptors remained maintained vision, while those below that threshold continued losing sight despite treatment. The same principle likely applies to optogenetics: intervene too late, and there may not be enough ganglion or bipolar cells left to engineer.

Safety has been remarkably good across multiple trials. The PIONEER trial's highest dose cohort was approved as safe by an independent data safety monitoring board after careful review. The MCO-010 RESTORE trial reported no serious adverse events - no severe intraocular inflammation, no retinal detachments, no vision-threatening complications.

The main procedural risk comes from the injection itself. Any time you stick a needle into an eye, there's a small risk of infection, bleeding, or inflammation. The sub-retinal delivery method used by some therapies intentionally creates a temporary retinal detachment to get the vector under the retina, then allows it to reattach. That sounds dramatic, but retinal surgeons do this routinely, and the risk is well-managed.

What about long-term safety? That's the billion-dollar question. These trials have follow-up data out to 76 weeks - about 18 months - showing sustained benefit without new safety signals. But what happens at five years? Ten years? The opsins are permanently integrated into the cells' DNA, so theoretically, they should keep working as long as those cells survive. Early data suggests that's exactly what happens, but we need more time to be certain.

One unique aspect of optogenetics is that the therapy requires specialized goggles, which means there's an ongoing dependence on hardware. Battery life, durability, and updates matter. On the flip side, this also means researchers can improve the system over time by upgrading the goggles without touching the patient's eye.

As of late 2024, no optogenetic therapy has received FDA approval yet, but several are racing toward that goal. The PIONEER trial is in Phase 1/2a, still establishing safety and preliminary efficacy. The RESTORE trial for MCO-010 completed its Phase 2b stage with positive top-line results announced in March 2024, positioning it for Phase 3 trials and eventual FDA submission.

For context, the first FDA-approved retinal gene therapy - voretigene neparvovec (Luxturna) - was approved in 2017 for a specific form of inherited retinal disease caused by RPE65 mutations. That therapy corrects the underlying genetic defect rather than engineering new light sensors, but it proved that retinal gene therapy could navigate the regulatory process successfully. Luxturna now has a five-year track record showing durability and safety, which paves the way for optogenetic approaches.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) is running parallel evaluations. The GS030 trial, developed by GenSight Biologics, enrolled patients in both the US and Europe, setting up potential dual-market approval if results pan out.

Dr. Arshad Khanani: "If approved, MCO-010 is poised to make a positive, meaningful impact on the lives of patients affected by this debilitating condition."

That's carefully worded - "if approved" does a lot of work in that sentence - but the optimism is clear. The data so far supports moving forward.

Let's talk about the elephant in the room: price. Luxturna, the only approved retinal gene therapy so far, costs $850,000 per patient for both eyes. It's one of the most expensive drugs in the world. Insurance coverage has been spotty, though many large insurers eventually agreed to cover it. Optogenetic therapies will likely land in a similar price range because the development costs are astronomical and the patient population is small.

The orphan drug designation that most retinal gene therapies receive provides regulatory incentives but doesn't guarantee affordability. Some health systems may adopt a value-based payment model where they only pay if the therapy works, spreading the risk between manufacturer and payer.

Geographic access is another hurdle. These procedures can only be performed at specialized centers with experienced retinal surgeons trained in sub-retinal or intravitreal gene delivery. Currently, only a handful of medical centers like Mayo Clinic have the capability. As approvals come through, that network will expand, but patients in rural or under-resourced areas may face significant barriers.

Then there's the global disparity. Even if optogenetics becomes standard of care in the US and Europe, it may be decades before it reaches patients in low- and middle-income countries where the burden of inherited blindness is just as severe.

What does daily life look like for someone who's received optogenetic therapy? First, there's intensive training. The visual signal is so different from natural sight that the brain needs to learn how to interpret it. Training sessions can last weeks or months, gradually increasing complexity from detecting light and dark to recognizing shapes and navigating spaces.

Patients must wear the goggles whenever they want to use their artificial vision, which means you're tethered to a piece of technology. Battery management becomes part of the routine. Some patients report that the grainy, monochromatic vision takes getting used to - it's more like thermal imaging than color photography.

But the functional gains are profound. One 58-year-old patient in the PIONEER trial who'd been blind for years was able to locate objects on a table and navigate around obstacles after treatment. That may not sound dramatic until you consider what it means: being able to move through your own home independently, knowing where the furniture is, seeing when someone enters the room. Small things that sighted people take for granted become possible again.

"People have tried electrical and optogenetic prosthetics for decades, since the early '90s, but these are the first really to provide form vision."

- Dr. Daniel Palanker, Stanford University

Quality-of-life measures show significant improvements. Patients report greater confidence, less dependence on caregivers, and a restored sense of agency. Depression and anxiety - common among people with progressive blindness - often improve once even rudimentary vision returns.

If you zoom out, optogenetics is part of a larger wave of neurotechnology that's redefining what's treatable. In the last decade, we've seen cochlear implants restore hearing to the deaf, brain-computer interfaces allow paralyzed patients to control robotic arms, and now optogenetics bringing sight to the blind. Each of these represents a fundamental shift from trying to fix the broken biological system to engineering an entirely new workaround.

Think back to how we treated infectious disease before antibiotics. You could drain an abscess or quarantine the sick, but you couldn't cure the infection. Then penicillin arrived and changed everything overnight. Gene therapy for blindness feels similar - a before-and-after moment in medicine. For decades, ophthalmologists could slow some forms of retinal degeneration with drugs or laser treatment, but once the photoreceptors died, that was the end of the line. Now we're in a world where dead photoreceptors don't mean permanent blindness.

The parallels to other medical breakthroughs are striking. Insulin didn't cure diabetes, but it transformed it from a death sentence to a manageable condition. Heart transplants didn't eliminate cardiovascular disease, but they gave patients a second chance. Optogenetics won't restore perfect vision, but it can give blind people functional sight - and that's transformative.

While current trials focus on retinitis pigmentosa and age-related macular degeneration, the potential applications are much broader. Any condition where photoreceptors are lost but inner retinal layers survive could theoretically benefit. That includes choroideremia, Stargardt disease, Leber congenital amaurosis, and dry AMD with geographic atrophy.

Each of these affects tens of thousands of patients in the US alone, with hundreds of thousands worldwide. If optogenetics proves durably effective, it could be adapted across this entire spectrum of diseases using essentially the same platform - just adjust the opsin, target cell type, or delivery method as needed.

Some researchers are also exploring optogenetics for partial vision restoration in conditions like glaucoma, where ganglion cells die gradually. Could you rescue remaining ganglion cells by making them more light-sensitive? That's speculative, but the biology suggests it's possible.

The current generation of optogenetic therapies uses opsins borrowed from algae and bacteria, but researchers aren't stopping there. Next-generation opsins are being engineered to be faster, more sensitive, and responsive to different wavelengths of light. Why does this matter?

Faster response times mean smoother, more natural-feeling vision. Current opsins can lag behind rapid movements, creating a blurred or delayed image. Improving kinetics could make the visual experience much more fluid.

Higher sensitivity means the therapy could work in lower light conditions, potentially allowing patients to see indoors without needing bright amber light constantly beamed into their eyes. The MCO-010 opsin is marketed as "ambient-light activatable," meaning it doesn't require specialized goggles - normal environmental light is sufficient. If that pans out, it would eliminate the hardware dependency entirely, making the therapy far more practical for everyday life.

Multicolor opsins responsive to red, green, and blue light could theoretically restore color vision instead of just grayscale. That's still experimental, but early lab work shows promise. Imagine going from seeing vague shapes in amber tones to perceiving actual colors again - the emotional impact would be immense.

While much attention focuses on the gene therapy itself, the quality of the visual interface hardware matters enormously. Current goggles use neuromorphic cameras - specialized sensors that detect changes in light intensity rather than capturing full frames like a traditional camera. This mimics how natural retinas work and can reduce latency.

But there's room for improvement. Higher pixel density in the light projectors means finer visual detail. Better signal processing algorithms can enhance edge detection, making objects stand out more clearly. Reducing latency between the camera input and light output can make movements feel more natural.

The PRIMA system's next-generation device is improving pixel density through engineering innovations, potentially boosting resolution significantly. Meanwhile, augmented reality platforms developed for gaming and military use are trickling into medical devices, bringing better displays and lighter, more comfortable form factors.

There's even talk of integrating AI-based scene recognition that could highlight important objects - a person's face, a doorway, a step down - to help patients navigate more safely. This blends optogenetics with computer vision in ways that could surpass what natural eyes can do in some contexts.

For patients living with progressive blindness, the promise of optogenetics is almost overwhelming. Online forums for retinitis pigmentosa patients buzz with questions: When will it be available? Will my insurance cover it? Am I too far gone? The desperate hope is palpable.

Patient advocacy groups have played a crucial role in pushing research forward. Organizations like the Foundation Fighting Blindness fund optogenetics research and connect patients with clinical trials. They also provide a reality check, emphasizing that current therapies offer limited vision, not a cure.

Testimonials from trial participants are mixed. Some express profound gratitude for regaining any vision at all. Others describe frustration with the limitations - the grainy quality, the training burden, the constant need to wear goggles. One patient noted, "I thought I'd be able to recognize my grandchildren's faces, but it's really more about navigating spaces." Managing expectations is critical.

There's also a poignant dimension for patients who've been blind for decades. The visual cortex - the part of the brain that processes sight - can atrophy from disuse. Even if optogenetics delivers light signals to the brain, will the brain remember how to interpret them? Early evidence suggests yes, the brain retains remarkable plasticity even after years of blindness, but the learning curve is steep.

Optogenetics will arrive unevenly across the world. Wealthier countries with advanced healthcare systems - the US, UK, Germany, Japan - will see access first. The regulatory infrastructure and specialized treatment centers required make it a high-resource intervention by design.

But inherited retinal diseases don't respect borders. Retinitis pigmentosa occurs at similar rates globally, affecting about 1 in 4,000 people. In countries with limited access to genetic testing and specialist care, many patients never even receive a proper diagnosis, let alone cutting-edge treatment.

International collaborations like the GS030 trial in Europe hint at efforts to broaden access, but it's a drop in the bucket. Without deliberate policies to ensure equitable distribution - subsidized pricing for low-income countries, training programs to build local expertise - optogenetics could become yet another technology that widens the health equity gap.

Some researchers advocate for open-source approaches where the basic science is shared freely, allowing researchers in any country to develop local versions. The challenge is that the manufacturing process for viral vectors and the precision required for retinal surgery create inherent barriers to low-cost production.

By 2029, if current trends hold, we'll likely see at least one optogenetic therapy approved for retinitis pigmentosa in the US and Europe. MCO-010 appears to be the frontrunner, with its Phase 2b data showing both statistical significance and durability out to 76 weeks. Phase 3 trials will likely launch in 2025, with approval potentially coming by 2027 if all goes well.

The PIONEER trial and other ganglion-cell-targeting approaches will follow, probably on a similar timeline. Each approval will expand the toolkit, offering different options for different patient profiles - some with higher resolution but requiring goggles, others with lower resolution but ambient-light activation.

Beyond individual therapies, the field is moving toward combination approaches. Could you pair optogenetics with neuroprotective drugs that preserve remaining retinal cells, maximizing the substrate available for treatment? Could you combine it with stem cell therapy that generates new bipolar or ganglion cells, expanding the treatable population?

The regulatory agencies are also evolving. The FDA's accelerated approval pathway for orphan diseases, successfully used for Luxturna, sets a precedent that optogenetic therapies will likely follow. If early trials show safety and functional benefit - even if it's not perfect vision - approval may come faster than traditional timelines would suggest.

Optogenetics' success in the eye has implications far beyond ophthalmology. The same principle - engineering non-functional cells to take over for dead ones - could apply to other parts of the nervous system. Researchers are already exploring optogenetics for treating deafness by making cochlear neurons light-sensitive, controlled by a light-emitting cochlear implant.

In spinal cord injury, optogenetic stimulation of specific neurons could help restore movement. In Parkinson's disease, light-sensitive neurons could replace dopamine-producing cells that have died. Each application faces unique challenges, but the eye proves the concept works.

The eye was the ideal starting point because it's relatively accessible - easier to reach with a needle than the brain or spinal cord - and the retina is optically transparent, allowing light to reach engineered cells without obstruction. But the lessons learned about vector design, cell targeting, and functional assessment all transfer to other systems.

One broader insight: engineering around a problem can be faster than solving it. We still don't know how to prevent photoreceptors from dying in retinitis pigmentosa - there are hundreds of genetic causes, each requiring a different fix. But by bypassing photoreceptors entirely, optogenetics sidesteps that entire complexity. This "workaround medicine" represents a philosophical shift that could accelerate treatment development across neurodegeneration.

Optogenetic therapy won't cure blindness in the traditional sense - it won't restore photoreceptors or reverse genetic mutations. But it offers something perhaps more important: functional vision where none existed before. In an era when so many medical breakthroughs are incremental, this one feels genuinely transformative.

The challenges ahead are real: regulatory approval, cost containment, equitable access, long-term safety monitoring, and hardware refinement. Each of those represents years of work. But the science is sound, the clinical results are encouraging, and the patient need is urgent.

For the 2 million people worldwide living with retinitis pigmentosa, and the millions more with other forms of photoreceptor degeneration, optogenetics represents the first viable path from darkness back toward light. Not perfect light, not natural light, but light nonetheless. And for someone who's been blind, that difference is everything.

"Such encouraging results with PRIMA devices point to a much better future."

- Dr. Mohajeet Bhuckory, Stanford University

That's the story here - not just a better future for vision science, but a fundamentally altered reality for patients who were told nothing more could be done. The darkness isn't permanent anymore. The light is coming back.

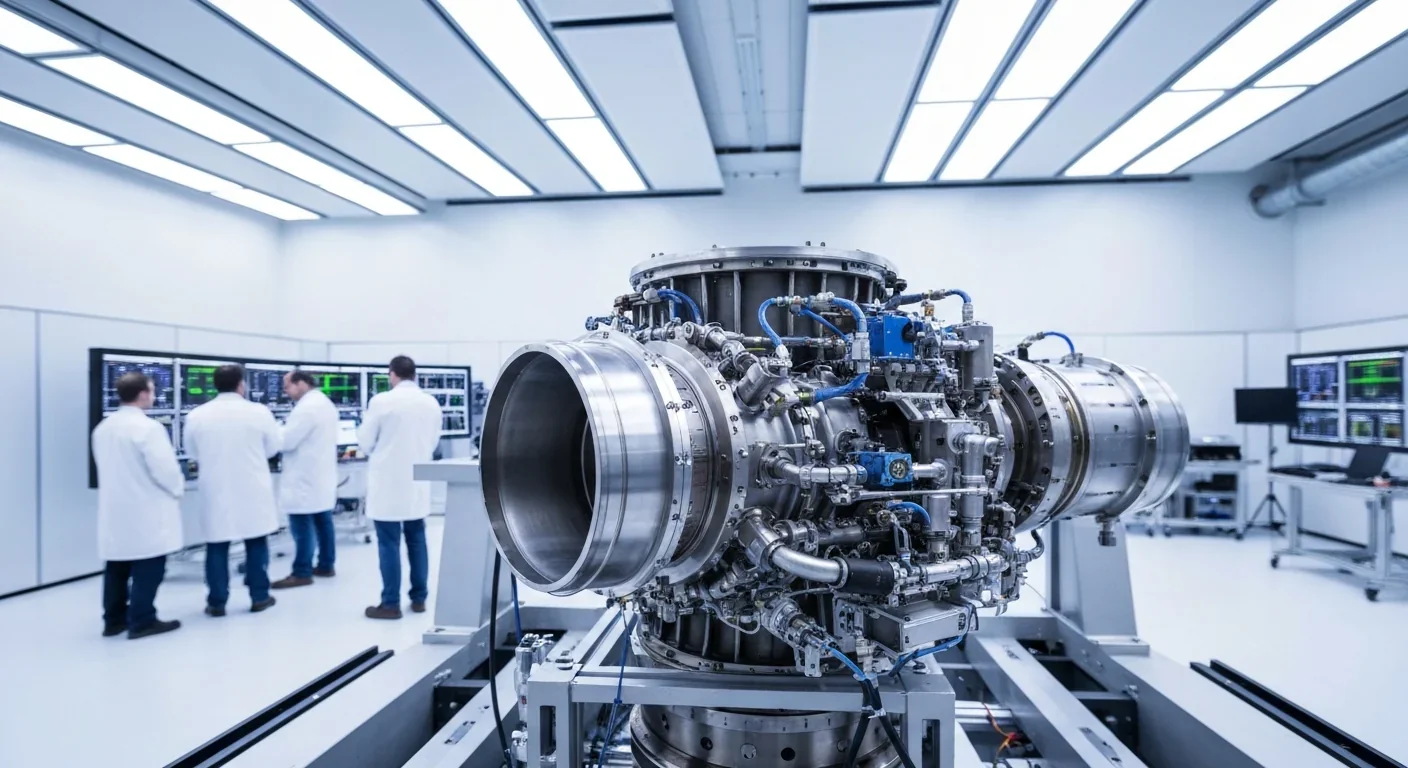

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

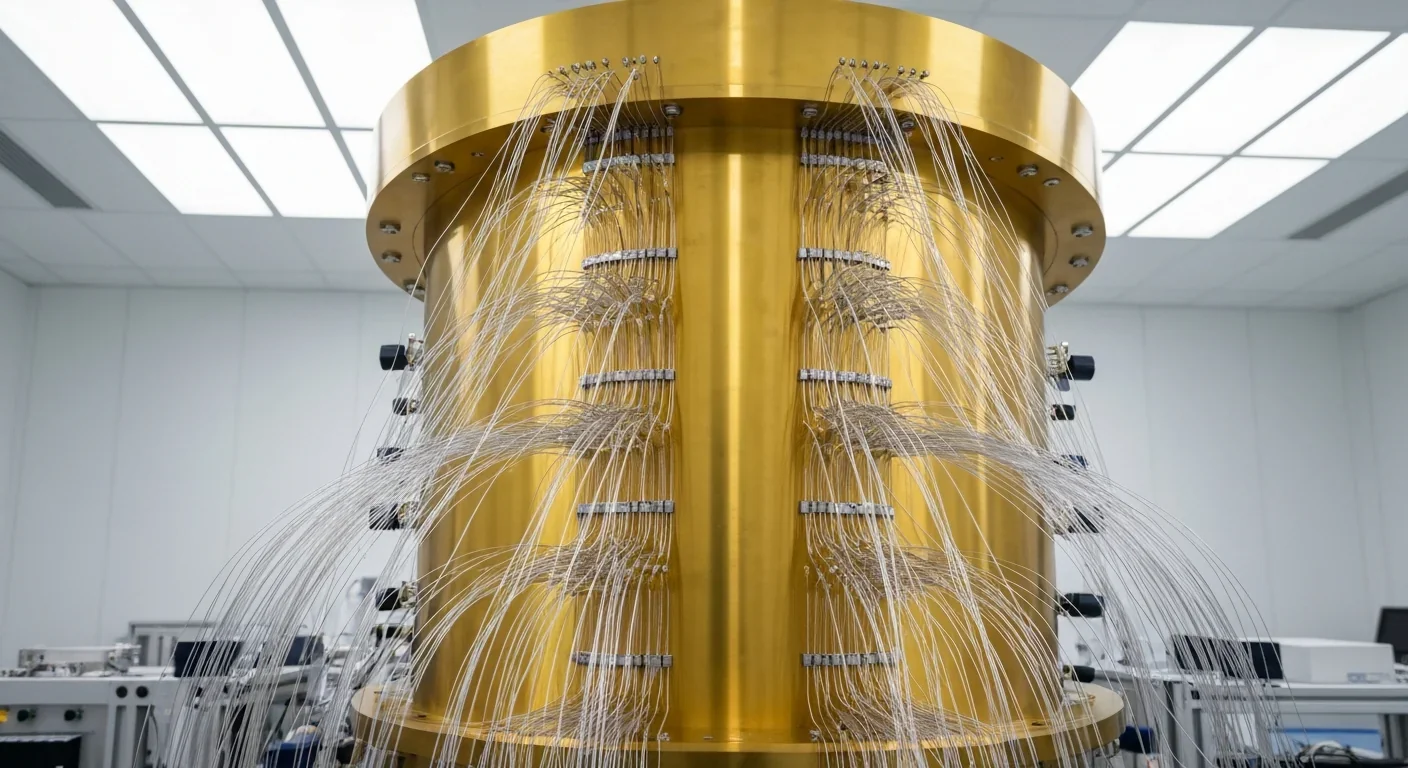

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.