Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: Deliberately cooling cardiac arrest patients to 32-34°C slows brain metabolism and prevents neurological damage, improving survival with good outcomes from 39% to 55%. This counter-intuitive intervention has evolved from strict protocols to flexible targeted temperature management.

Within minutes of your heart stopping, your brain begins to die. Yet doctors have discovered something remarkable: making you colder can stop that process. By 2030, researchers predict therapeutic hypothermia will become standard emergency protocol worldwide, fundamentally changing how we think about the boundary between life and death. What started as an accidental observation has evolved into a precise medical intervention that's rewriting the rules of resuscitation.

When your heart stops during cardiac arrest, the clock starts ticking immediately. Brain cells begin dying within 4-6 minutes of oxygen deprivation, leading to irreversible damage if blood flow isn't restored quickly.

Here's the cruel irony: the moment blood flow returns, a cascade of inflammatory responses floods the brain, potentially causing more harm than the initial oxygen deprivation. This phenomenon, called reperfusion injury, creates a secondary wave of cellular damage that can destroy neurons for hours or days after resuscitation.

The traditional approach treated cardiac arrest survivors with standard intensive care, hoping the brain could heal itself. Results were grim. Only about 39% of patients survived with favorable neurological outcomes using conventional methods. The majority either died or survived with severe brain damage.

The solution sounds absurd: deliberately lower the patient's body temperature to 32-34°C (89.6-93.2°F), several degrees below normal. Yet this simple intervention fundamentally changes the brain's response to oxygen deprivation.

Cold slows everything down at the cellular level. For every one degree Celsius drop in body temperature, cellular metabolism slows by 5-7%, reducing the brain's desperate need for oxygen and glucose. Think of it like putting your phone in low-power mode when the battery is dying. The brain conserves its limited energy stores, extending the window during which cells can maintain basic functions and avoid catastrophic damage.

For every one degree Celsius drop in body temperature, cellular metabolism slows by 5-7%, dramatically reducing the brain's oxygen demands and extending the window for potential recovery.

But the benefits go far beyond simple metabolic slowdown. Cooling suppresses the inflammatory cascade that causes reperfusion injury, reduces the production of harmful free radicals, and prevents the buildup of excitatory neurotransmitters that can kill neurons. At a brain temperature of 14°C during deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, surgeons can safely stop blood flow for 30-40 minutes during complex procedures.

The mechanism is so effective that case reports document patients surviving 96 minutes of continuous CPR and achieving complete neurological recovery when therapeutic hypothermia was applied.

The idea of therapeutic cooling isn't new. Ancient physicians like Hippocrates observed that cold could preserve life, packing wounded soldiers in snow. But modern therapeutic hypothermia emerged from landmark trials published in 2002 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

These studies randomized 346 adults who had been resuscitated from cardiac arrest to either cooling (32-34°C) or normal temperature management. The results were striking: 55% of cooled patients achieved favorable neurological outcomes, compared to just 39% in the control group.

"The landmark 2002 trials showed 55% of cooled patients achieved favorable neurological outcomes, compared to just 39% in the control group - a dramatic improvement that revolutionized post-cardiac arrest care."

- New England Journal of Medicine, 2002

The evidence was compelling enough that medical societies worldwide rapidly updated their guidelines. By the mid-2000s, therapeutic hypothermia became recommended standard of care for comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, particularly those with shockable rhythms like ventricular fibrillation.

But a 2013 trial called TTM challenged the prevailing wisdom by comparing strict cooling to 33°C versus more moderate cooling to 36°C. Surprisingly, both groups showed similar outcomes, suggesting that preventing fever might be more important than achieving aggressive hypothermia. This finding sparked ongoing debate about optimal target temperatures.

Implementing therapeutic hypothermia requires precision timing and careful monitoring. The intervention works best when started within 6 hours of return of spontaneous circulation. One study using a thermoelectric hypothermia helmet achieved initiation within an average of 32.9 minutes after cardiac arrest.

Doctors use several methods to cool patients. Surface cooling applies ice packs or cooling blankets to the skin. More sophisticated systems use intravascular cooling catheters inserted into large veins, circulating cold saline to achieve unparalleled precision. These devices can lower body temperature at rates of 1.5-2°C per hour and maintain temperatures within ±0.1°C of target.

Newer technologies like thermoelectric cooling helmets offer non-invasive localized brain cooling without the systemic complications of whole-body hypothermia. These devices can achieve target temperature within about 214 minutes and maintain it for extended periods without causing skin injuries.

The cooling phase typically lasts 24-72 hours, during which medical teams must manage numerous physiological challenges. Patients are heavily sedated because the body naturally fights against cooling through shivering.

Then comes perhaps the most critical phase: rewarming. This must be done slowly and carefully, typically at rates of 0.1-0.5°C per hour, to avoid spikes in intracranial pressure or rebound hyperthermia. Rapid rewarming is associated with worse neurological outcomes, potentially undoing all the benefits of the cooling phase.

Not every cardiac arrest patient receives therapeutic hypothermia. The intervention works best for specific populations. Ideal candidates are comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with shockable rhythms who achieved return of spontaneous circulation but remain unconscious despite successful resuscitation.

The evidence for other populations remains mixed. In children following cardiac arrest, cooling does not appear useful as of 2018, though therapeutic hypothermia dramatically improves outcomes in newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. An umbrella review of neonatal studies found therapeutic hypothermia reduced neonatal mortality by 18% and lowered disability risk by 35% in low- and middle-income settings.

Timing matters enormously. Studies in acute spinal cord injury found early initiation within 6 hours was consistently linked with superior functional improvement. The same principle applies to cardiac arrest, where every minute of delay potentially reduces the intervention's effectiveness.

The statistics tell a compelling story. In a study using thermoelectric craniocerebral cooling, overall survival reached 75%, and 62.5% of survivors achieved good neurological outcomes, meaning they could return to independent living with minimal or no neurological deficits.

With therapeutic hypothermia, 75% of cardiac arrest patients survived, and 62.5% achieved good neurological outcomes - able to return to independent living with minimal deficits.

These numbers represent more than statistics. They translate to thousands of people each year who walk out of hospitals and return to their families instead of dying or surviving with devastating brain damage. The difference between 39% favorable outcomes with standard care and 55% with therapeutic hypothermia means that for every 100 cardiac arrest survivors, hypothermia saves roughly 16 additional people from death or severe disability.

Therapeutic hypothermia isn't without risks. Cooling the body affects nearly every physiological system. Common complications include bradycardia, arrhythmias, coagulopathy, electrolyte disturbances, and increased infection risk. Blood doesn't clot as effectively when cold. The heart's electrical system becomes unstable, sometimes triggering dangerous rhythms.

Passive cooling methods frequently result in hypothermic overshoot, where core temperature drops below 32°C, and rebound hyperthermia during rewarming. These temperature fluctuations correlate with increased mortality and worse neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The resource intensity presents another challenge. Therapeutic hypothermia requires sophisticated monitoring equipment, trained staff, and intensive care unit capacity. In low- and middle-income countries where cardiac arrest incidence is high, these resources may not be available. The umbrella review on neonatal hypothermia highlighted a significant practice gap: therapeutic hypothermia proves effective in these settings when implemented, yet remains underutilized due to infrastructure limitations.

There's also the question of prognostication. Sedation and hypothermia make it extremely difficult to assess neurological function during treatment. Doctors can't reliably predict which patients will recover until days after rewarming is complete.

Medical guidelines have evolved rapidly as evidence accumulates. The journey from strict 33°C cooling to broader "targeted temperature management" reflects medicine's willingness to revise practices based on new data.

Current American Heart Association and European Resuscitation Council guidelines recommend maintaining temperatures between 32-36°C for at least 24 hours, with active prevention of fever for at least 72 hours post-arrest. The emphasis has shifted from achieving a specific cold temperature to avoiding hyperthermia, which consistently worsens outcomes.

"The shift to broader temperature ranges appears driven by recognition that preventing fever, rather than achieving strict 33°C, is the key factor for improved outcomes."

- Evidence from TTM trials and guideline updates

This evolution demonstrates an important principle in emergency medicine: sometimes preventing harm (fever) matters more than inducing a theoretical benefit (deep cooling). Perhaps cooling protects the brain less through dramatic metabolic suppression and more through preventing the inflammatory fever response that commonly occurs after cardiac arrest.

The success of therapeutic hypothermia in cardiac arrest has sparked investigation into other conditions. Researchers are exploring cooling for traumatic brain injury, stroke, and spinal cord injury.

Results have been mixed. A systematic review of therapeutic hypothermia in acute traumatic spinal cord injury found trends toward benefit but statistical imprecision due to small sample sizes. The intervention appears safe, with manageable complications, and early initiation (within 6 hours) correlated with better functional improvement.

In traumatic brain injury, initial enthusiasm has been tempered by large trials showing no clear benefit and potential harm from some protocols. The brain injury context differs from cardiac arrest in important ways: the injury is often focal rather than global, bleeding risk is higher, and the pathophysiology involves direct trauma rather than pure ischemia.

Yet the search continues because the potential payoff is enormous. Traumatic brain injury and stroke affect millions globally each year, often striking young people and leaving devastating lifelong disabilities.

Innovation in cooling technology continues advancing. Traditional surface cooling with ice packs was crude and difficult to control. Modern systems offer precision that would have seemed impossible two decades ago.

Intravascular cooling catheters represent the current gold standard for control, maintaining temperatures within 0.1°C of target and allowing rapid adjustments. But they're invasive, requiring insertion into large central veins, which carries risks.

The thermoelectric hypothermia helmet demonstrates an alternative approach: non-invasive localized brain cooling that avoids systemic side effects. By using thermoelectric modules that can heat or cool by reversing electrical current, these devices offer controlled transition between temperatures without invasive procedures.

Looking ahead, researchers are investigating pharmacological approaches that might mimic hypothermia's benefits without actually cooling the body. If scientists could develop drugs that slow metabolism, suppress inflammation, and protect against reperfusion injury as effectively as cooling does, the logistical challenges of temperature management might become obsolete.

In high-income countries with advanced emergency medical systems, therapeutic hypothermia has become relatively routine. Most major hospitals have protocols, equipment, and trained staff. But the global picture looks very different.

The majority of cardiac arrests worldwide occur in settings with limited resources. The proven effectiveness in low- and middle-income countries highlights an urgent practice gap. When implemented, therapeutic hypothermia reduces mortality and disability substantially in these settings, yet most patients never receive it.

In low- and middle-income countries, therapeutic hypothermia reduced neonatal mortality by 18% and disability by 35% - yet most patients worldwide never receive this proven treatment due to resource constraints.

The barriers are formidable: lack of intensive care capacity, insufficient trained personnel, competing priorities for limited resources, and sometimes the complete absence of basic monitoring equipment. Even simpler surface cooling methods require continuous nursing attention and temperature monitoring that may not be available.

Addressing this gap requires more than just sending equipment. Sustainable implementation needs training programs, protocol development adapted to local conditions, and healthcare system strengthening. The ethical dimension is sharp: a proven life-saving intervention remains inaccessible to most of the world's population due to economic and infrastructure constraints.

Therapeutic hypothermia has fundamentally changed how medicine thinks about the boundary between life and death. The traditional definition of death as the irreversible cessation of cardiopulmonary function has become more complicated when interventions like cooling can extend the window of reversibility.

During deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, patients experience what the medical literature carefully calls "managed clinical death." The heart stops completely, blood pressure drops to zero, brain activity ceases on EEG. Yet with precise temperature control and surgical timing, patients wake up afterward with intact neurological function.

This redefinition matters beyond academic philosophy. It affects decisions about when to start resuscitation, how long to continue it, and when to withdraw care. The case reports of patients surviving 96 minutes or even hours of CPR with good outcomes when therapeutic hypothermia was employed challenge the conventional time limits that guide termination of resuscitation efforts.

As our ability to preserve and protect the brain improves, the window of potential recovery extends. What seemed impossible becomes routine. The definition of "too late" keeps moving.

Behind every statistic about therapeutic hypothermia lies a human story. Families keeping vigil in intensive care units as their loved ones lie motionless, cooled below normal temperature, sedated deeply enough that assessing neurological function becomes impossible.

For those who do wake with intact cognitive function, therapeutic hypothermia represents a second chance at life. They were dead, then brought back not just to biological existence but to the full richness of human consciousness, memory, relationships, and experience. The intervention literally gave them back themselves.

"Therapeutic hypothermia literally redefines clinical death. Patients survive 'managed clinical death' where the heart stops, blood pressure drops to zero, and brain activity ceases - yet they wake up afterward with intact neurological function."

- Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest research

For healthcare providers, therapeutic hypothermia represents the best of evidence-based medicine: a rational intervention grounded in clear physiological mechanisms, validated through rigorous trials, refined through ongoing research, and proven to save lives and preserve what matters most about being human.

The counter-intuitive nature of the treatment, deliberately making sick people colder when our instinct is to warm them, embodies medicine's willingness to challenge assumptions and follow evidence wherever it leads. Sometimes the answer isn't what we expect. Sometimes saving lives means freezing them first.

As therapeutic hypothermia transitions from cutting-edge intervention to standard care, and as research pushes into new applications and refined protocols, we're witnessing medicine's ongoing evolution. The boundary between life and death isn't as fixed as we once thought. With precision, timing, and a few degrees of cooling, we can pull people back from the edge and give them another chance at the life they almost lost.

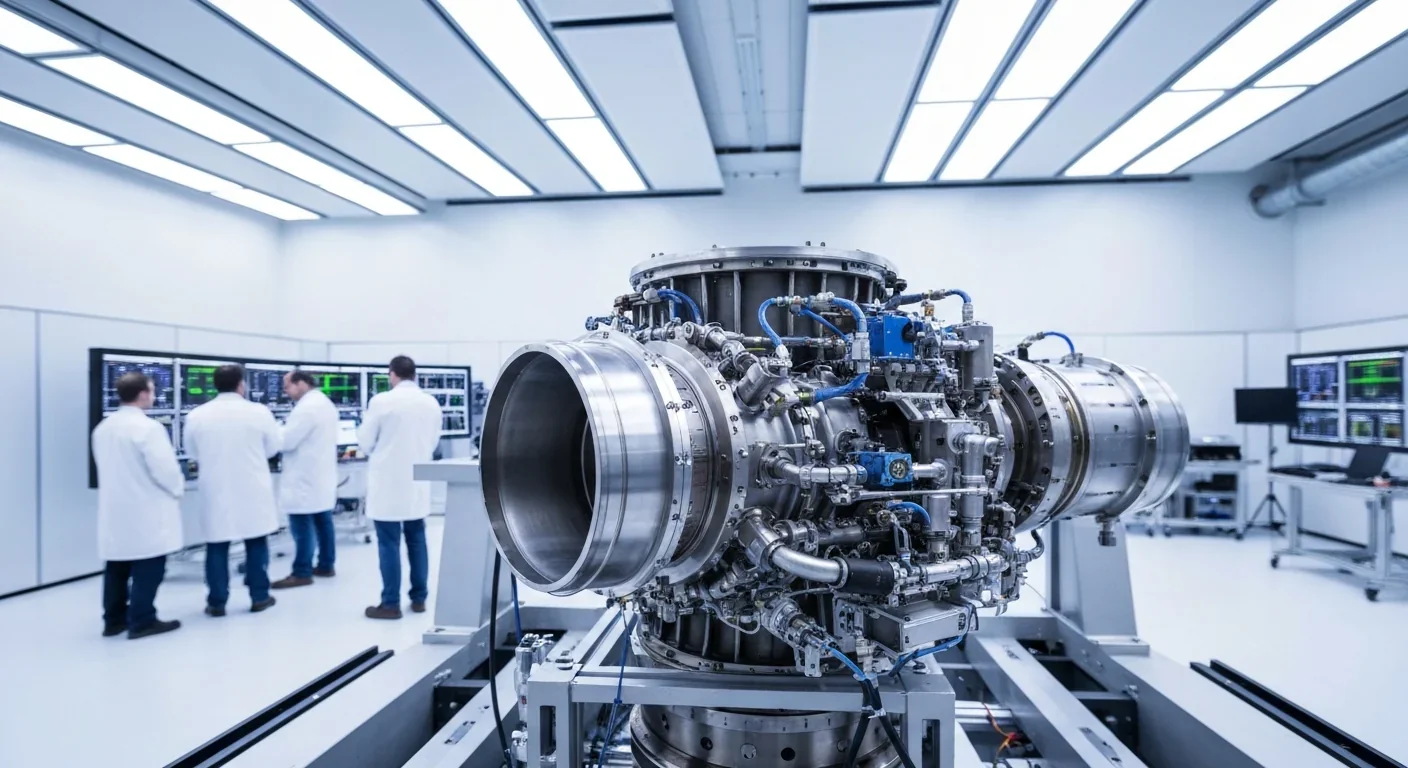

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

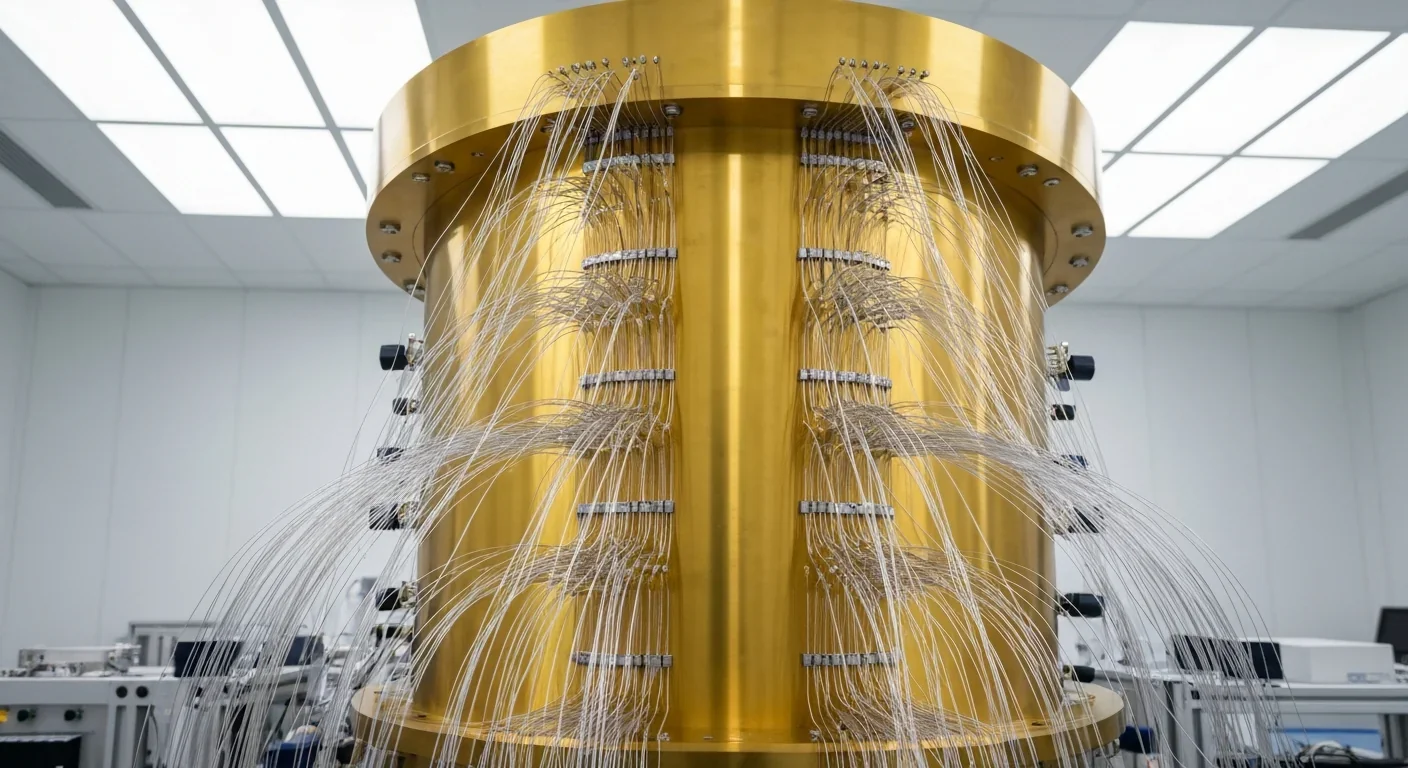

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.