Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: Scientists have discovered that tissue stiffening isn't just a symptom of aging and cancer - it's an active driver. The extracellular matrix hardens over time, mechanically instructing cells to malfunction, age faster, and become cancerous. This paradigm shift is spawning new therapies that target tissue mechanics rather than just cells, potentially revolutionizing treatment for age-related diseases and cancer.

Your body is betraying you in ways you never imagined. Not through mutations or toxins, but through something far more insidious: the gradual hardening of the invisible scaffolding that holds your cells together. Scientists have discovered that as tissues stiffen with age, they don't just lose flexibility - they actively instruct your cells to malfunction, age faster, and even become cancerous. This mechanical dimension of disease represents one of the most profound paradigm shifts in modern medicine, and it's rewriting everything we thought we knew about aging and cancer.

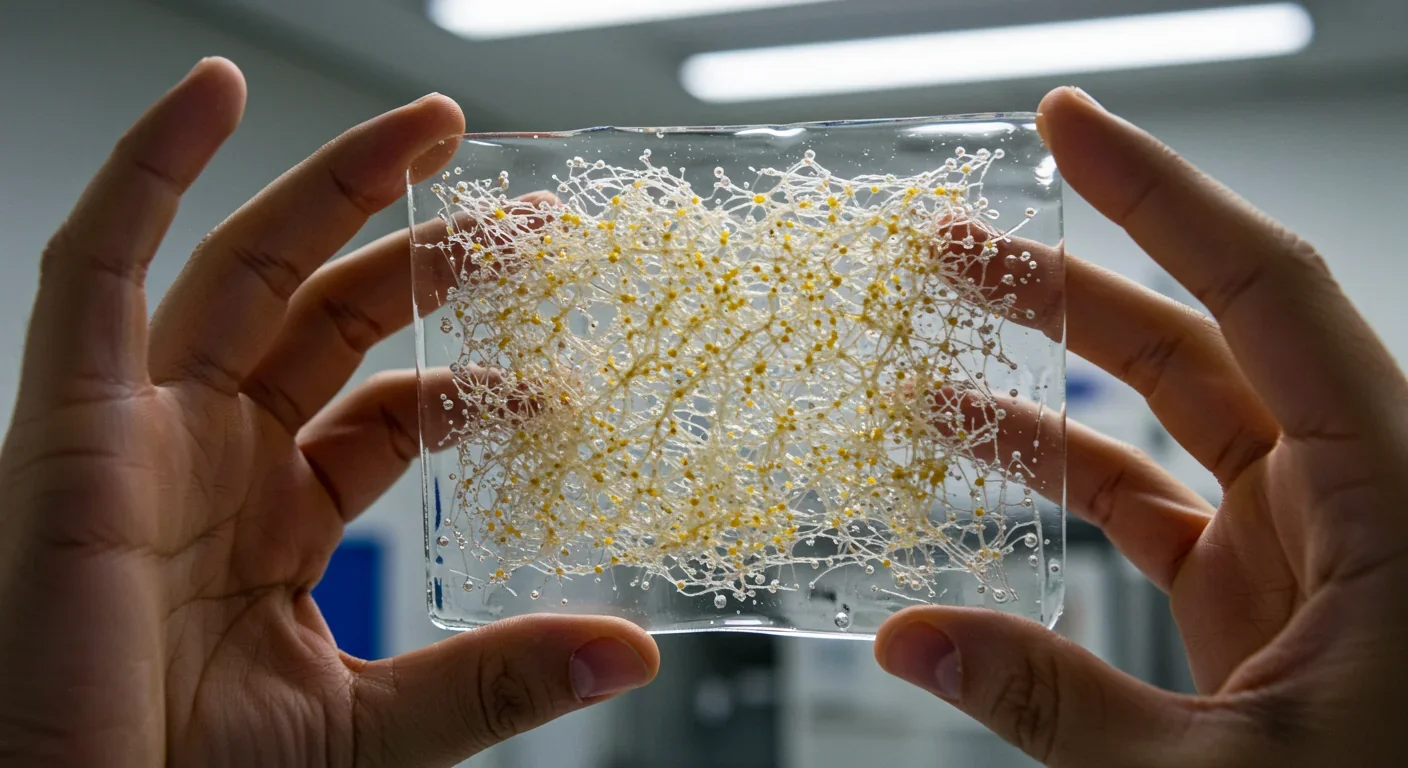

Between every cell in your body exists an intricate network called the extracellular matrix (ECM) - a three-dimensional scaffolding composed primarily of proteins like collagen and elastin. This isn't just passive structural support. The ECM is a dynamic communication system that tells your cells how to behave, when to divide, where to migrate, and whether to live or die.

Collagen alone makes up roughly one-third of all protein in your body, forming resilient fibers that provide tensile strength to everything from your skin to your blood vessels. Elastin provides the bounce-back quality that lets tissues stretch and recoil. Together with hundreds of other proteins, sugars, and signaling molecules, these components create what researchers now recognize as an intelligent material - one that actively shapes cellular destiny.

For decades, scientists viewed the ECM primarily as structural scaffolding. That perspective has been completely upended. We now know that the physical properties of this matrix - particularly its stiffness - exert profound control over cellular behavior through a process called mechanotransduction.

Your cells are constantly probing their surroundings, sensing mechanical cues just as surely as they detect chemical signals. This happens through specialized receptor proteins embedded in the cell membrane - primarily integrins and discoidin domain receptors - that physically connect the cell's internal skeleton to the extracellular matrix outside.

When these receptors bind to collagen fibers in the ECM, they don't just anchor the cell in place. They initiate cascades of biochemical signals that travel into the nucleus and alter gene expression. A cell on soft tissue receives completely different instructions than the same cell on rigid tissue, even if the chemical environment is identical.

The key signaling pathways include focal adhesion kinase (FAK), which activates when integrins cluster together on stiff substrates, and the YAP/TAZ transcription factors, which shuttle into the nucleus on rigid surfaces but remain inactive in the cytoplasm when tissues are soft. These aren't minor regulatory tweaks - they're fundamental switches that control whether cells proliferate, differentiate, migrate, or enter senescence.

Mechanical forces don't just influence cells - they fundamentally reprogram cellular identity. A stem cell on soft substrate becomes a neuron. The same cell on rigid substrate becomes bone. The stiffness matters as much as the chemistry.

Researchers have demonstrated this principle using atomic force microscopy to measure tissue stiffness with nanoscale precision. Normal, healthy liver tissue has a Young's modulus (a measure of stiffness) of around 0.5 kilopascals. Cirrhotic liver tissue can measure 15 kilopascals or higher. Cells cultured on substrates mimicking these different stiffnesses show dramatically different gene expression profiles, growth rates, and survival characteristics.

The mechanical environment literally reprograms cellular identity. A stem cell placed on a soft substrate resembling brain tissue will differentiate toward neurons. The same stem cell on a rigid substrate resembling bone will become an osteoblast. This phenomenon, called "mechanosensitive differentiation," reveals how deeply mechanical forces shape biology.

As we age, our tissues progressively stiffen. This isn't just a consequence of aging - it's a driver of it. The process creates a vicious cycle that accelerates tissue dysfunction and disease progression.

Multiple mechanisms contribute to age-related tissue stiffening. Cross-linking of collagen increases as enzymes like lysyl oxidase (LOX) become more active or as non-enzymatic glycation occurs through reactions with sugars. These cross-links form permanent chemical bonds between collagen fibers, turning the once-flexible matrix into a rigid mesh.

Chronic inflammation, which increases with age in a process called inflammaging, further remodels the ECM. Inflammatory signals trigger fibroblasts to produce more collagen and less elastin, shifting the balance toward rigidity. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), enzymes that normally maintain ECM homeostasis by degrading and remodeling matrix proteins, become dysregulated - sometimes overactive, sometimes insufficient - resulting in abnormal ECM architecture.

Perhaps most insidiously, increased matrix stiffness directly induces cellular senescence. Senescent cells are those that have permanently stopped dividing but remain metabolically active, secreting inflammatory factors that damage surrounding tissues. Research on pulmonary fibrosis has shown that mechanical stiffness alone can push lung epithelial cells into senescence through degradation of nuclear proteins like lamin A/C. These senescent cells then contribute to further ECM remodeling, creating a feed-forward loop.

"Tissue stiffness creates a vicious cycle: stiffening drives cellular senescence, senescent cells secrete inflammatory factors, and inflammation causes more stiffening. Breaking this loop is key to healthy aging."

- Recent findings in pulmonary fibrosis research

The implications extend throughout the body. In the brain, age-related stiffening of the meningeal extracellular matrix impairs the clearance of waste products through the lymphatic system, potentially contributing to neurodegeneration. In blood vessels, arterial stiffening increases cardiovascular disease risk. In skin, loss of elasticity and increased cross-linking manifest as wrinkles and reduced wound healing capacity.

Each stiffened tissue becomes an aging accelerator. The mechanical changes alter cellular behavior in ways that promote further stiffening, inflammation, and functional decline. Breaking this cycle has become a major focus of longevity research.

The link between tissue mechanics and cancer is even more direct and alarming. Tumors don't just happen to be stiff - they actively remodel their microenvironment to become stiffer, and this stiffness is a critical enabler of cancer progression.

In breast cancer, increased mammographic density, which correlates with ECM stiffness, is one of the strongest risk factors for developing malignancy. Women with extremely dense breast tissue have four to six times higher cancer risk than women with predominantly fatty breasts. This isn't just because dense tissue makes tumors harder to detect - the stiffness itself promotes malignant transformation.

Once a tumor begins forming, cancer cells and associated fibroblasts dramatically reshape the surrounding ECM in a process called desmoplasia. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) secrete massive amounts of collagen, up to ten times more than normal fibroblasts. They also produce high levels of LOX, which cross-links this collagen into dense, rigid networks.

This stiffened tumor microenvironment has multiple pro-cancer effects. Mechanically, the rigid matrix provides physical tracks that cancer cells use to invade surrounding tissue. The aligned collagen fibers act like highways that guide metastatic cells away from the primary tumor. Studies using multiphoton microscopy have captured cancer cells actively migrating along these straightened collagen bundles.

The mechanical forces also activate signaling pathways that make cancer cells more aggressive. Integrin engagement on stiff matrix activates the PI3K/AKT pathway, promoting cell survival and proliferation. YAP/TAZ activation drives a more stem-like, therapy-resistant phenotype. Matrix stiffness enhances the formation of invadopodia - specialized protrusions that cancer cells use to degrade the ECM and push through tissue barriers.

The stiffened tumor microenvironment acts as an immunosuppressive fortress. Dense collagen physically excludes T cells and natural killer cells, preventing them from reaching cancer cells even when immunotherapy successfully activates them.

Perhaps most concerningly, the stiffened tumor microenvironment creates an immunosuppressive fortress. The dense collagen matrix physically excludes immune cells, preventing T cells and natural killer cells from infiltrating the tumor. Even when immunotherapy drugs successfully activate anti-tumor immunity, those activated immune cells often can't penetrate the mechanical barrier to reach cancer cells. This mechanical immunosuppression is a major reason why many cancers don't respond to checkpoint inhibitor therapies.

Stiffness also affects cancer metabolism and therapy resistance. The mechanical stress activates signaling pathways that upregulate drug efflux pumps, DNA repair mechanisms, and anti-apoptotic proteins. Pancreatic cancer, one of the deadliest malignancies, is characterized by extreme desmoplasia - the tumor can be up to 90% fibrotic tissue. This mechanical density collapses blood vessels within the tumor, making it nearly impossible for chemotherapy drugs to reach cancer cells.

If tissue stiffness drives disease, then measuring it becomes crucial for early detection and treatment monitoring. Several technologies are bringing mechanical diagnostics into clinical practice.

Elastography has emerged as a non-invasive imaging technique that maps tissue stiffness. Ultrasound-based shear-wave elastography sends acoustic pulses into tissue and measures how fast the resulting shear waves propagate - faster waves indicate stiffer tissue. This technology is now routinely used to assess liver fibrosis, reducing the need for invasive biopsies.

In breast cancer, combining traditional ultrasound imaging with shear-wave elastography significantly improves diagnostic accuracy. Malignant tumors are typically much stiffer than benign masses or normal tissue, and quantifying this stiffness helps radiologists distinguish cancer from false alarms, potentially reducing unnecessary biopsies.

Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) provides similar information with better penetration depth, useful for assessing organs like the liver, brain, and prostate. Research groups are developing optical coherence elastography and photoacoustic elastography for even higher resolution mapping of superficial tissues.

At the research frontier, atomic force microscopy can measure the mechanical properties of individual cells or small tissue samples with extraordinary precision. While not yet a clinical tool, AFM has been instrumental in revealing how cancer cells on stiff substrates become more aggressive and how normal cells respond to pathological stiffness.

These diagnostic advances support a future where mechanical properties are routinely assessed alongside biochemical markers, providing a more complete picture of tissue health and disease risk.

Understanding the mechanical dimension of disease has opened entirely new therapeutic strategies. Rather than targeting only cancer cells or inflammatory pathways, researchers are developing interventions that normalize tissue mechanics.

LOX inhibitors represent one promising approach. By blocking lysyl oxidase enzymes, these drugs prevent the cross-linking of collagen, maintaining ECM flexibility. Recent studies in triple-negative breast cancer showed that potent LOX inhibitors not only reduced tumor stiffness but also dramatically enhanced the effectiveness of chemotherapy. Softer tumors allowed better drug penetration and forced cancer cells to revert to less aggressive phenotypes.

Collagenase therapies are being tested to directly degrade excess collagen in tumors. Bacterial collagenase has shown promise in preclinical studies, breaking down the dense fibrotic barrier and allowing immune cells to infiltrate tumors. Combining collagenase with immunotherapy produced synergistic effects in animal models, with some tumors completely regressing when both treatments were used together.

The anti-fibrotic drug pirfenidone, already approved for treating pulmonary fibrosis, is being repurposed to prevent ECM stiffening in cancer. By reducing fibroblast activity and collagen synthesis, pirfenidone may prevent the mechanical evolution of tumors into therapy-resistant fortresses.

"We're not just fighting cancer cells anymore. We're targeting the mechanical fortress they build around themselves. Soften the tumor, and suddenly all our other weapons become far more effective."

- Mechanobiology researchers developing combination therapies

Matrix metalloproteinase modulators offer another avenue. Rather than simply inhibiting MMPs (which failed in previous clinical trials), newer strategies aim to restore proper MMP balance, allowing physiological ECM remodeling while preventing pathological fibrosis.

Researchers are also exploring mechanotherapeutics that directly interfere with mechanotransduction signaling. Inhibitors of FAK, the kinase activated by stiff matrices, have entered clinical trials. By blocking the signal that tells cells they're on rigid tissue, these drugs may trick cancer cells into behaving as if they're in a soft, normal environment - reducing their aggressiveness regardless of actual ECM stiffness.

Innovative combination approaches show particular promise. Several clinical trials are testing ECM-normalizing agents alongside standard treatments. The hypothesis is simple but powerful: soften the tumor, then attack it with conventional weapons that previously couldn't penetrate the fortress.

The insights from cancer research are now informing anti-aging interventions. If tissue stiffening drives aging, then maintaining ECM flexibility might extend healthspan.

Several longevity interventions already in use may work partly through ECM effects. Caloric restriction, the most robust aging intervention across species, reduces inflammatory signaling that drives pathological ECM remodeling. Exercise mechanically loads tissues in ways that promote healthy ECM maintenance rather than pathological stiffening. Both interventions lower LOX activity and advanced glycation end-products.

Senolytics - drugs that selectively eliminate senescent cells - are being tested for their ability to reverse age-related tissue stiffening. Since senescent cells drive fibrosis through their inflammatory secretions, removing them may allow the ECM to gradually return to a more youthful state. Early clinical trials in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and osteoarthritis show encouraging signs of ECM normalization.

Supplementation strategies are being explored. Compounds that break existing collagen cross-links, like certain advanced glycation end-product breakers, might reverse established stiffening. Elastin precursors or stimulators of elastin production could help restore the balance between rigid and flexible ECM components.

The emerging field of "mechanomedicine" envisions comprehensive approaches to maintaining healthy tissue mechanics throughout life. This might include periodic measurement of tissue stiffness as a biomarker of biological age, targeted interventions when stiffening begins, and lifestyle modifications designed to maintain ECM flexibility.

This mechanical revolution in biology isn't happening everywhere equally. Research funding and focus varies dramatically across regions, reflecting different healthcare priorities and scientific traditions.

European research institutions have been particularly strong in translating mechanobiology findings into clinical applications. The European Research Council has funded multiple large-scale projects on ECM mechanics in cancer and aging. European pharmaceutical companies are leading development of several LOX inhibitors and ECM-normalizing drugs currently in trials.

Asian research centers, particularly in Japan and South Korea, have contributed extensively to understanding age-related ECM changes and their connection to longevity. Japanese researchers made key discoveries about how elastin degradation products drive aging through immune system activation - work that directly built on observations in Japan's remarkably long-lived population.

North American institutions dominate fundamental mechanotransduction research, with dozens of labs dissecting the signaling pathways that translate mechanical forces into biochemical responses. The National Institutes of Health have increasingly recognized the importance of physical forces in biology, establishing specific funding programs for mechanobiology research.

Global research equity remains a challenge: Most mechanobiology research occurs in high-income countries with expensive imaging technology, while lower-income regions bearing substantial disease burden have limited access to these advances.

However, significant gaps remain in global research equity. Most mechanobiology research occurs in high-income countries with access to expensive imaging and measurement technologies. Lower-income regions, where the burden of fibrotic diseases and cancer is substantial, have limited capacity to participate in this research revolution or access emerging diagnostics and therapies.

International collaboration is addressing some disparities. The Human Frontier Science Program and similar organizations fund multinational research teams studying ECM mechanics. Open-source initiatives are developing lower-cost elastography devices suitable for resource-limited settings. But much work remains to ensure the benefits of mechanomedicine reach all populations.

The mechanical dimension of health has immediate practical implications. While targeted mechanotherapies are still emerging, understanding tissue stiffness can inform decisions today.

Exercise becomes even more important when viewed through a mechanical lens. Regular physical activity maintains ECM flexibility through beneficial mechanical loading. Weight-bearing exercise stimulates healthy collagen remodeling rather than pathological cross-linking. The mechanical signals from exercise may be as important as the metabolic benefits.

Chronic inflammation, whether from obesity, poor diet, stress, or environmental exposures, drives pathological ECM stiffening. This provides another mechanism by which inflammation accelerates aging and disease - beyond the biochemical damage, it literally hardens your tissues. Anti-inflammatory lifestyle interventions take on new significance.

For cancer patients, the stiffness paradigm suggests important questions to discuss with oncologists. Is my tumor particularly fibrotic? Would elastography provide useful prognostic information? Are there clinical trials testing ECM-normalizing approaches for my cancer type? As mechanotherapies advance, these conversations will become increasingly relevant.

Anyone with a family history of fibrotic diseases - pulmonary fibrosis, liver cirrhosis, kidney disease - should be aware that tissue stiffness is an early, potentially modifiable feature of these conditions. Early detection through elastography, before symptoms appear, may create a window for intervention.

The broader lesson is that tissue health isn't just about what's happening inside cells - it's about the physical environment those cells inhabit. A cell in a rigid, aged microenvironment will malfunction even if its DNA is pristine. Conversely, normalizing the mechanical environment might coax dysfunctional cells back toward health.

We're at the beginning of a fundamental reconceptualization of disease. The recognition that physical forces shape biology as powerfully as genes and chemicals opens vast therapeutic space. Every disease involving ECM dysfunction - which includes most age-related pathologies and essentially all solid tumors - becomes a potential target for mechanical intervention.

The next decade will likely see the first FDA-approved mechanotherapies specifically designed to normalize tissue stiffness. LOX inhibitors are furthest along, with several candidates in late-stage trials. Combination approaches pairing ECM normalization with immunotherapy or chemotherapy may become standard cancer treatment protocols.

Diagnostic medicine will incorporate routine stiffness measurements alongside blood tests and genetic screening. Your annual physical might include elastography to catch the earliest signs of pathological tissue changes, years before symptoms appear. Biological age might be assessed partly through tissue stiffness profiles across multiple organs.

Longevity interventions will explicitly target ECM health. Rather than viewing aging as purely genetic or metabolic, the field will embrace the mechanical dimension. Compounds that maintain youthful tissue flexibility could become as common as antioxidants and anti-inflammatories in the supplement aisle.

The challenges are substantial. ECM biology is enormously complex, varying by tissue type, age, and disease state. Interventions that normalize stiffness in one context might cause problems in another - some tissues need to be rigid to function properly. Translating elegant laboratory findings into safe, effective therapies for millions of patients requires years of careful work.

But the fundamental insight stands: your tissues have a memory, encoded not just in genes but in physical structure. As that structure changes, it reshapes cellular behavior in profound ways. Disease isn't just happening to your cells - it's happening to the mechanical world they inhabit. Change that world, and you might change your health destiny.

The revolution in mechanomedicine is here. Your tissues are already in conversation with your cells, conducting an endless dialogue through physical forces. Scientists are finally learning that language. And as we learn to speak it, we're discovering we can change the conversation - bending the trajectory of aging and disease in ways that seemed impossible just a decade ago.

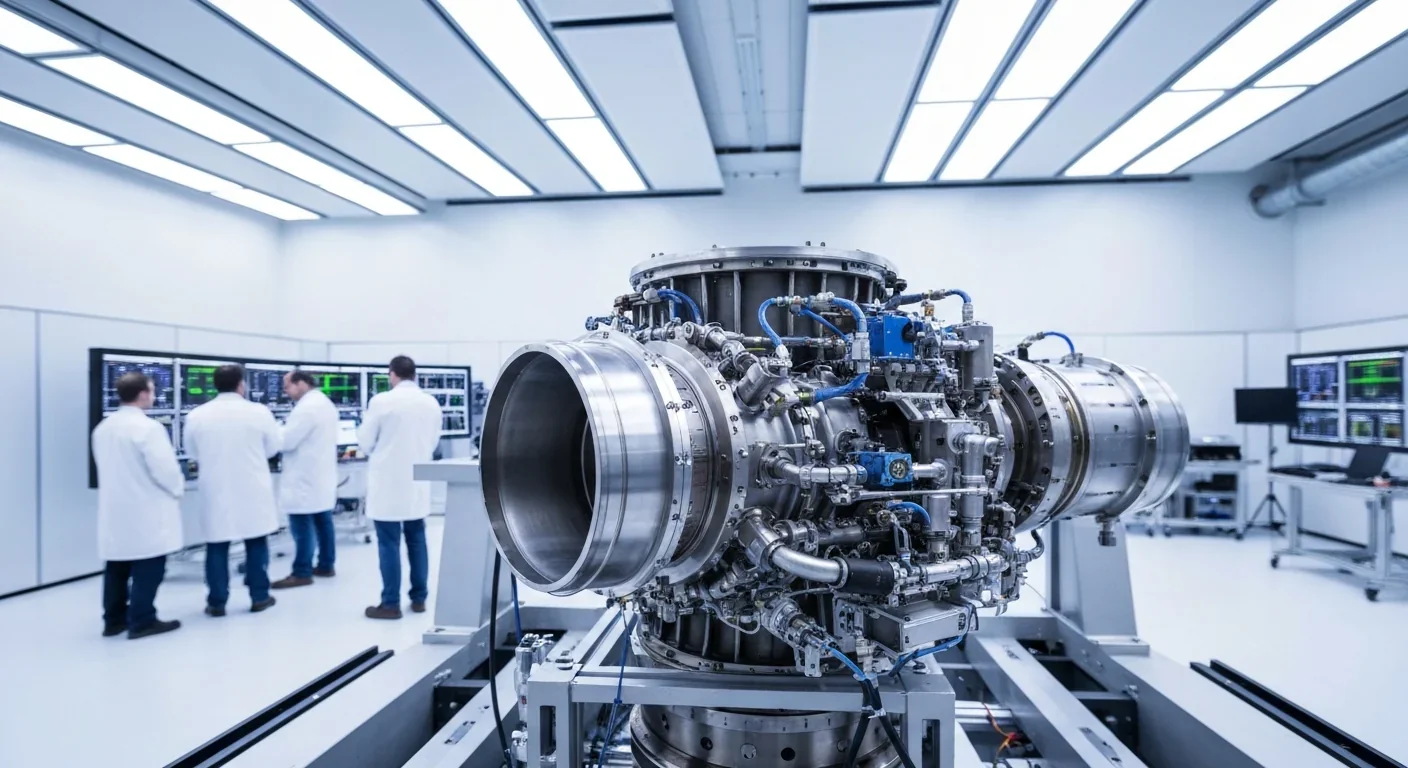

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

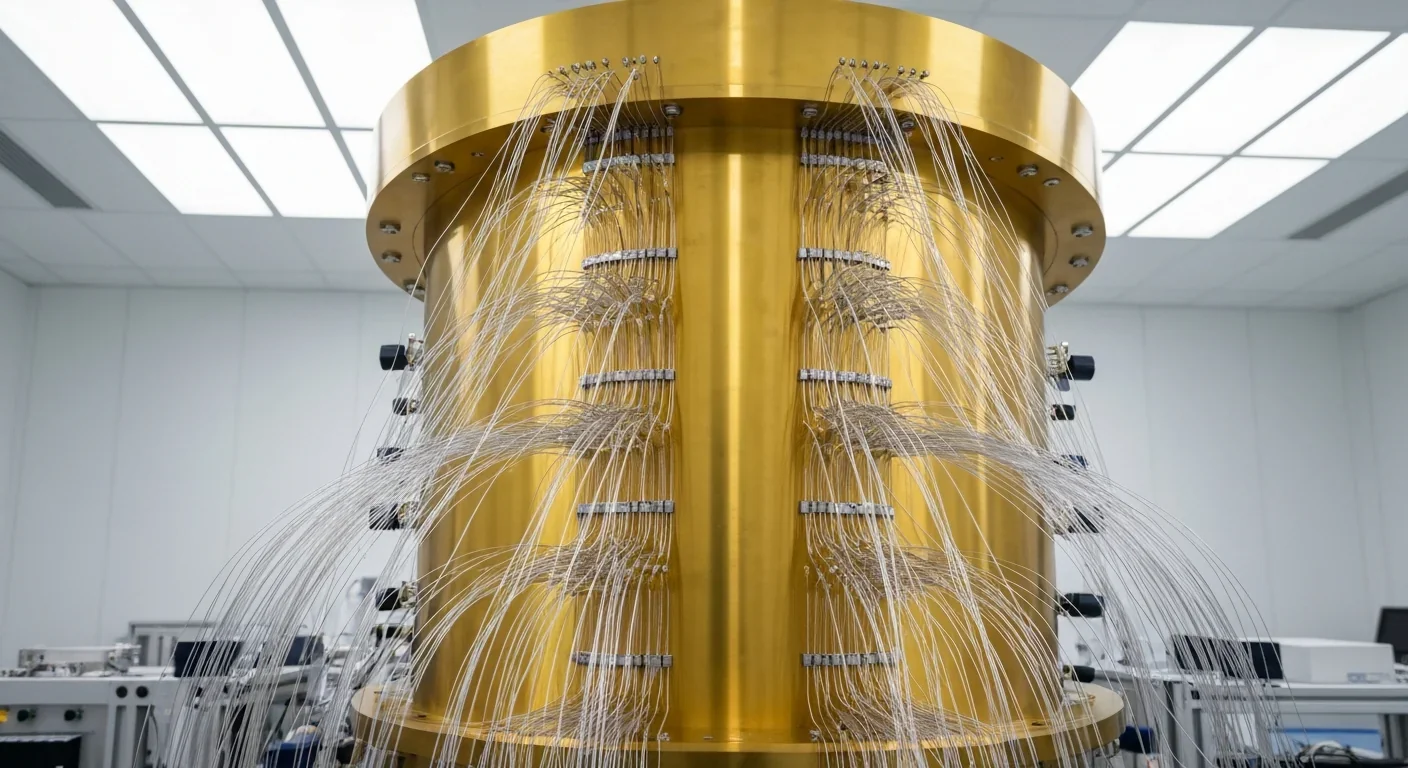

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.