Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: Chemical cocktails can transform one cell type into another without altering DNA, offering a safer path to regenerative medicine than genetic methods. The first human trial showed success in treating diabetes, and applications span from neurological diseases to cardiac repair.

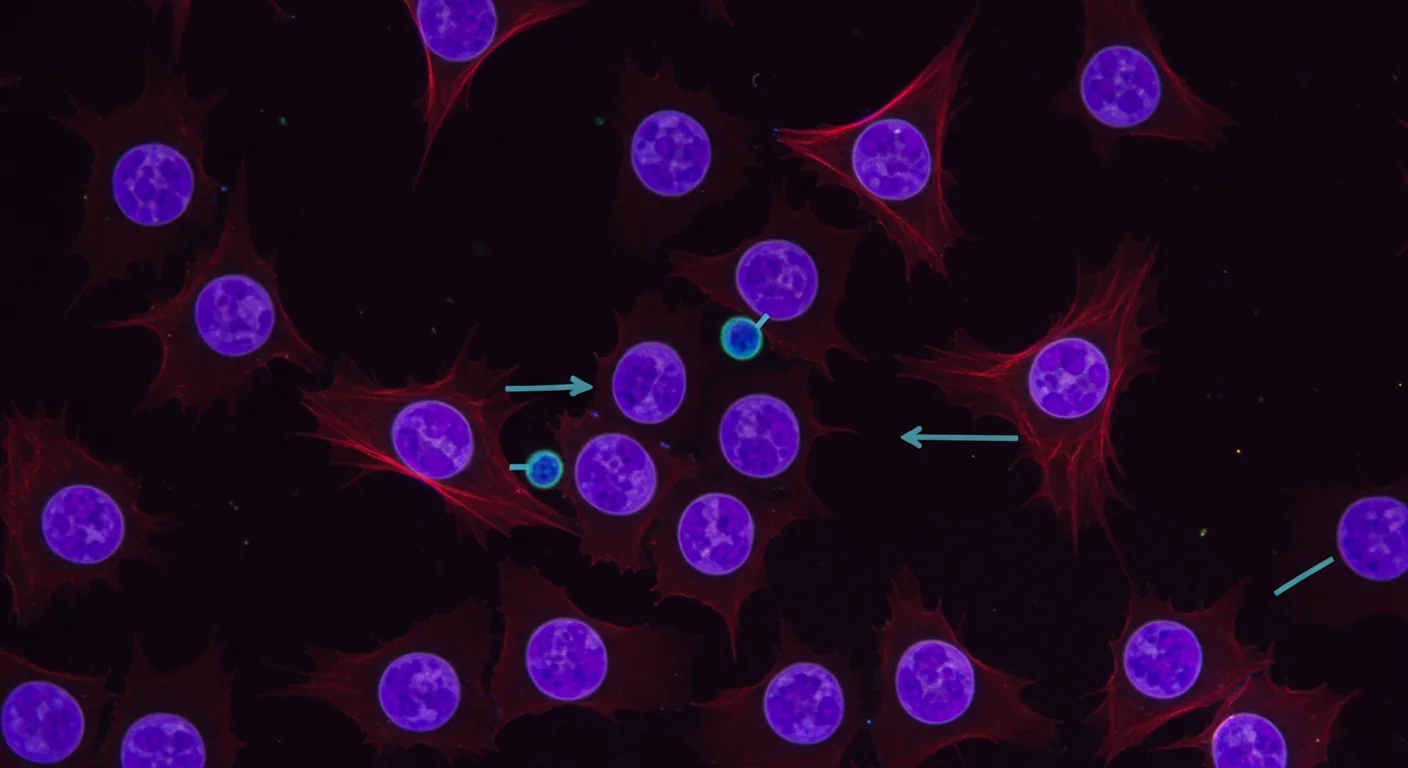

Inside a laboratory dish, a skin cell begins to forget what it is. Not through genetic engineering or viral manipulation - just a carefully designed mixture of chemical compounds. Within weeks, that cell transforms into a neuron, a heart cell, or even returns to an embryonic-like state capable of becoming any cell type in the body. This isn't science fiction. It's chemical reprogramming, and it's quietly revolutionizing regenerative medicine by offering something the field has desperately needed: a safer path forward.

The breakthrough matters because it sidesteps the biggest obstacle that has plagued stem cell therapy for decades. Traditional methods of cellular reprogramming rely on inserting genes into cells using viruses - an approach that works but carries the risk of triggering cancer or causing unpredictable genetic changes. Chemical reprogramming achieves the same transformation using only small molecules that the body can metabolize and clear, leaving no permanent genetic fingerprint behind.

At its core, chemical reprogramming exploits a fundamental truth about biology: cell identity isn't hardwired into DNA. Instead, it's maintained by an elaborate system of epigenetic modifications - chemical tags attached to DNA and the proteins around it that determine which genes are active and which stay silent. These modifications are reversible, and that reversibility is the key.

Chemical cocktails work by simultaneously targeting multiple epigenetic regulators and signaling pathways. Some compounds remove repressive marks from DNA, like stripping old paint off a canvas. Others add activating marks or block signals that lock cells into their current identity. The magic happens when you combine the right molecules in the right proportions - suddenly, cellular barriers that seemed permanent dissolve.

Consider the pioneering work by Deng et al. in 2013, who demonstrated the first fully chemical reprogramming to pluripotency using a seven-compound cocktail. Each chemical in their mixture targeted a different molecular pathway - one inhibited DNA methylation, another blocked histone deacetylases, a third activated specific developmental signals. Together, they created a molecular environment that essentially convinced adult cells they were embryonic again.

The compounds themselves read like an alphabet soup to non-scientists: DZNep, A-83-01, CHIR99021, valproic acid. But each serves a precise function. Valproic acid, originally developed as an anti-seizure medication, turns out to be remarkably good at opening up tightly packed DNA, making genes accessible again. CHIR99021 activates the Wnt signaling pathway, which plays a crucial role in maintaining stem cell properties. A-83-01 blocks signals that push cells toward differentiation.

By 2017, researchers refined these approaches further. The Chou laboratory developed an eight-compound protocol that could reliably generate human induced pluripotent stem cells from adult skin cells - no genes required. The efficiency wasn't as high as genetic methods yet, but it worked, and it was safe.

Chemical reprogramming achieves cellular transformation using only small molecules that the body can metabolize and clear, leaving no permanent genetic modifications - addressing the biggest safety concern in regenerative medicine.

The real test of any medical technology isn't whether it works in a dish - it's whether it can safely treat human disease. On this front, chemical reprogramming recently crossed a crucial threshold. In 2024, researchers reported the first human transplantation of insulin-producing islet cells derived from chemically induced pluripotent stem cells in a Type 1 diabetes patient. The patient achieved durable insulin independence, meaning their body's own immune system didn't reject the cells and they no longer needed insulin injections.

This wasn't just a technical achievement - it was proof of concept that chemically reprogrammed cells could function normally in a living human body. The cells knew what to do. They sensed blood sugar levels, produced insulin in response, and integrated into the patient's physiology as if they belonged there all along.

The pathway to this success involved multiple innovations. Researchers developed improved cocktails that dramatically enhanced stem cell survival during the freezing and thawing process necessary for clinical banking. The CEPT cocktail - a combination of a ROCK inhibitor, an antioxidant, and two other compounds - reduced cell death during cryopreservation from catastrophic levels to manageable ones, making it practical to create cell banks for therapeutic use.

Other teams focused on speed and efficiency. A 2023 protocol by Liuyang and colleagues shortened the reprogramming timeline from 50 days to 30 days while simultaneously improving the success rate. Every day matters when you're trying to generate therapeutic cells for a patient who's waiting, so these incremental improvements add up to major practical advantages.

"Each single drop of fingerstick blood can yield more than 100 chemically induced pluripotent stem colonies."

- Research findings on blood-based reprogramming

Perhaps most remarkably, researchers figured out how to reprogram cells from blood - a far more accessible source than skin biopsies. A fingerstick worth of blood, the kind you'd use for a glucose test, contains enough cells to generate hundreds of pluripotent stem cell colonies using chemical methods. This matters enormously for scalability and patient comfort.

Neurological diseases have always been among the hardest to treat because the brain doesn't readily replace damaged neurons. Chemical reprogramming offers a workaround: convert other cells directly into neurons or generate neural progenitors from pluripotent cells.

A comprehensive systematic review identified 33 experimental protocols using exclusively small molecules to transdifferentiate non-neural cells into neural lineages. The approaches varied - some converted fibroblasts into neurons, others transformed blood cells, and still others coaxed pluripotent cells toward specific neuronal subtypes - but they all shared the same DNA-free methodology.

The implications extend beyond just replacing lost neurons. Chemical reprogramming enables researchers to create patient-specific brain cells in a dish, providing unprecedented models of neurological diseases. You can take skin cells from a patient with Alzheimer's disease, reprogram them into neurons using chemicals, and then study exactly what goes wrong in that individual's brain cells. This personalized disease modeling is already accelerating drug discovery and helping researchers understand why some people develop certain neurological conditions while others don't.

The heart presents a different challenge. Unlike some organs, the adult human heart barely regenerates on its own. When heart muscle dies during a heart attack, it's generally gone forever, replaced by scar tissue that can't contract. Chemical reprogramming offers potential solutions.

Researchers have developed protocols using remarkably complex chemical cocktails - some containing up to 20 different compounds - to convert fibroblasts directly into beating cardiomyocytes. These aren't pluripotent cells that could become anything; they're direct conversions from one mature cell type to another therapeutically relevant type, a process called transdifferentiation.

The advantage of direct conversion is speed and safety. You skip the pluripotent stage entirely, avoiding the risk that some cells might not fully differentiate and could potentially form tumors. The cells go straight from fibroblast to cardiomyocyte, guided by the chemical cocktail.

Some cardiac reprogramming protocols now use up to 20 different compounds working in concert - each targeting specific molecular pathways to guide cells through the complex journey from one identity to another.

Other applications are emerging across regenerative medicine. Researchers have used chemical methods to expand salivary gland progenitor cells, potentially offering treatments for patients who've lost salivary function due to radiation therapy or Sjögren's syndrome. The chemicals don't just reprogram the cells - they maintain them in a proliferative state while preserving their ability to differentiate into functional salivary tissue when needed.

The safety profile of chemical reprogramming represents its most compelling advantage. Traditional genetic reprogramming using Yamanaka factors requires inserting four specific genes into cells, typically using viral vectors. This process works remarkably well - Shinya Yamanaka won the Nobel Prize for developing it - but it has downsides.

Viral integration can disrupt important genes or activate oncogenes that promote cancer. The inserted genes themselves include c-Myc, which is notorious for its role in many cancers. While researchers have developed workarounds, including using viruses that don't integrate into chromosomes or omitting c-Myc from the cocktail, the genetic approach fundamentally involves making permanent changes to the cell's DNA.

Chemical reprogramming eliminates these concerns entirely. The small molecules enter cells, do their job, and then get metabolized and excreted. They leave no lasting genetic trace. If something goes wrong during the reprogramming process, you can simply stop adding the chemicals and the cells will revert or die - there's no permanent genetic modification to worry about.

This matters tremendously for regulatory approval and clinical translation. Regulatory agencies like the FDA have extensive frameworks for evaluating small molecule drugs; they've been doing it for decades. Cell therapies using genetically modified cells face much more complex regulatory pathways because the risk profiles are less well understood.

Studies of chemically reprogrammed cells have shown encouraging safety data. Cells maintained in chemical reprogramming media for 15 passages retained normal karyotypes - meaning their chromosomes remained stable without accumulating mutations. They showed suppressed senescence markers, indicating they weren't prematurely aging. And critically, when differentiated into mature cell types, they functioned normally.

Despite rapid progress, chemical reprogramming still faces significant hurdles before it can become routine clinical practice. Efficiency remains the most obvious limitation. While genetic reprogramming can convert 1-2% of starting cells into pluripotent stem cells, chemical methods often achieve rates in the 0.1-0.5% range. That means you need many more starting cells or longer culture times to generate enough therapeutic cells.

The cocktails themselves present challenges. Optimizing these multi-component mixtures requires testing countless combinations - a task that's labor-intensive and expensive. Researchers use high-throughput screening approaches, sometimes testing hundreds of compound combinations, but the chemical space is vast. There might be far more efficient cocktails we haven't discovered yet simply because we haven't tried the right combinations.

Reproducibility is another concern. Small changes in cell culture conditions, compound purity, or timing can significantly affect outcomes. What works beautifully in one laboratory might fail or perform poorly in another unless every detail is precisely controlled. This makes it harder to standardize protocols for clinical use.

"The combinatorial design of small molecules allows modular tuning of lineage outcomes, positioning chemical reprogramming as a versatile platform for both pluripotency and direct lineage conversion."

- Analysis of chemical reprogramming strategies

The mechanism itself isn't fully understood. While we know these chemicals alter epigenetic marks and signaling pathways, the exact sequence of molecular events during reprogramming remains somewhat mysterious. Cells don't simply flip from one identity to another - they pass through intermediate states that are poorly characterized. Understanding these transitions better could help researchers design more efficient cocktails or identify problematic cells that might pose safety risks.

Scale presents practical challenges too. Manufacturing enough cells for even a single patient requires significant resources and time. Scaling up to treat thousands of patients will require automation, standardization, and significant manufacturing infrastructure - investments that pharmaceutical companies are only beginning to make as the technology proves itself.

Chemical reprogramming research has become a truly international effort, with major contributions coming from labs across Asia, North America, and Europe. China has been particularly aggressive in pushing this technology toward clinical applications, conducting the diabetes islet transplant that marked the field's first human trial. Chinese researchers have also been prolific in publishing protocols and refinements, contributing many of the efficiency improvements of the past few years.

Japanese researchers, building on their country's legacy in iPSC research, have focused on understanding the fundamental mechanisms and developing protocols for specific therapeutic applications. European groups have emphasized safety and regulatory frameworks, conducting detailed genetic and epigenetic analyses of chemically reprogrammed cells to understand their long-term stability.

American institutions, particularly the National Institutes of Health, have invested heavily in developing the supporting technologies that make chemical reprogramming practical - improved culture systems, better cryopreservation methods, and high-throughput screening platforms. The NIH's commitment to making these tools and protocols available to the broader research community has accelerated progress by preventing duplication of effort.

This global collaboration, enabled by rapid publication in open-access journals and preprint servers, means that breakthroughs in one laboratory quickly become available to others. A technique developed in Beijing can be refined in Boston and applied clinically in Berlin within months rather than years.

Chemical reprogramming doesn't exist in isolation - it's increasingly being combined with other cutting-edge technologies to enhance its capabilities. One particularly promising direction involves pairing chemical reprogramming with physical and mechanical cues.

Researchers have found that the physical environment profoundly influences reprogramming efficiency. Growing cells on surfaces with specific stiffness, or in three-dimensional structures rather than flat dishes, can improve conversion rates several-fold. Super-hydrophobic microwell arrays, which facilitate the transition from two-dimensional monolayers to three-dimensional cell clusters, boost reprogramming efficiency by approximately five-fold compared to conventional culture methods.

The integration of chemical approaches with gene editing technologies like CRISPR offers another frontier. Imagine using chemicals to reprogram cells into a desired type, then using CRISPR to make precise corrections to disease-causing mutations, all while avoiding the insertional mutagenesis risks of viral vectors. This combinatorial approach could enable highly personalized cell therapies tailored to each patient's specific genetic background and disease.

Artificial intelligence is also entering the picture. Machine learning algorithms can analyze the results of thousands of experiments, identifying patterns that humans might miss and suggesting novel compound combinations to test. This could dramatically accelerate the discovery of more efficient cocktails and help researchers understand which cellular characteristics predict successful reprogramming.

An intriguing application of chemical reprogramming extends beyond replacing damaged cells to actually rejuvenating aged ones. Researchers have found that transient exposure to reprogramming cocktails - not enough to fully convert cells to pluripotency, but enough to partially reset their epigenetic age - can reverse some aspects of cellular aging.

Studies in progeroid syndromes, rare genetic disorders that cause premature aging, have shown that chemical reprogramming can suppress senescence markers and restore some youthful characteristics to aged cells. The cells don't lose their identity - a skin cell remains a skin cell - but they function better, dividing more readily and showing reduced signs of age-related damage.

This opens fascinating questions about whether chemical cocktails could be used to treat age-related diseases more broadly, or even to extend healthy lifespan. Could periodic treatment with reprogramming cocktails help maintain tissue function in elderly people? Could they prevent or delay the onset of age-related conditions like osteoarthritis or cognitive decline?

These questions remain speculative, and the risks of partial reprogramming in living organisms are poorly understood. Cells that are incompletely reprogrammed might behave unpredictably, potentially becoming cancerous or dysfunctional. But the basic concept - that cellular aging is reversible through chemical means - represents a profound shift in how we think about aging as a biological process.

Several factors will determine how quickly chemical reprogramming moves from laboratory bench to bedside. First is the completion of additional clinical trials demonstrating both safety and efficacy across multiple applications. The diabetes trial provided crucial proof of concept, but regulators and the medical community will want to see consistent results across multiple patients and indications before embracing the technology widely.

Manufacturing and quality control represent another critical pathway. Pharmaceutical companies and academic centers are developing Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) facilities capable of producing chemically reprogrammed cells under the stringent quality standards required for therapeutic use. These facilities need to demonstrate they can reliably produce cells with consistent properties, free from contamination, and meeting all safety specifications.

Cost will matter enormously. Early cell therapies have been extraordinarily expensive - hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars per patient - limiting their accessibility. Chemical reprogramming offers potential cost advantages because it doesn't require the custom viral vectors needed for genetic approaches, but achieving truly affordable cell therapies will require further manufacturing innovations and economies of scale.

Regulatory frameworks continue evolving to accommodate these new technologies. The FDA and equivalent agencies worldwide are developing guidelines specifically for chemically reprogrammed cells, recognizing that they pose different risks and benefits compared to genetically modified cells. Clear regulatory pathways will accelerate development by giving companies confidence in what standards they need to meet.

The first human transplantation of insulin-producing islet cells derived from chemically induced pluripotent stem cells achieved durable insulin independence - proof that these cells can function normally in living patients.

Chemical reprogramming represents more than just a safer alternative to genetic methods - it's a fundamentally new way of thinking about cellular identity and therapeutic possibility. The realization that cell fate is fluid, that cellular identity can be rewritten with the right molecular signals, transforms our understanding of biology and opens therapeutic avenues that seemed impossible just years ago.

Within the next decade, we'll likely see chemical reprogramming-based therapies for multiple conditions. Diabetes appears poised to be among the first, given the successful initial trial and the relatively straightforward path to generating functional islet cells. Parkinson's disease represents another promising target, as researchers have demonstrated reliable chemical conversion of cells into dopaminergic neurons - the specific cell type that degenerates in Parkinson's patients.

Heart disease, macular degeneration, spinal cord injury - the list of conditions potentially treatable with chemically reprogrammed cells is extensive. Not all of these applications will pan out; some will prove technically challenging or less effective than hoped. But even if chemical reprogramming succeeds in treating just a handful of currently incurable conditions, it will transform millions of lives.

The technology might also democratize regenerative medicine by making it more accessible globally. Chemical compounds can be manufactured and distributed more easily than viruses or complicated biologics. A hospital in Jakarta or Nairobi could potentially implement chemical reprogramming protocols with appropriate training and equipment, whereas genetic approaches might remain concentrated in wealthy countries with advanced biotechnology infrastructure.

Perhaps most profoundly, chemical reprogramming changes our relationship with our own biology. Cells are no longer locked into the identities they acquire during development - they can be coaxed, convinced, reprogrammed to serve new purposes. We're no longer passive recipients of the cells we're born with; we're active architects of our own cellular composition.

That power comes with responsibility. As with any transformative technology, chemical reprogramming will raise ethical questions about enhancement versus therapy, access and equity, and the boundaries of acceptable intervention in human biology. Society will need to grapple with these questions thoughtfully as the technology matures.

But standing here at the beginning of this revolution, watching as researchers literally rewrite cellular identity using nothing but carefully designed molecular cocktails, it's hard not to feel a sense of possibility. The cells in your body are more plastic, more malleable, more open to change than we ever imagined. And that plasticity, guided by scientific insight and clinical wisdom, might just be the key to treating diseases that have plagued humanity for millennia.

The cocktails are mixed. The protocols are being refined. The clinical trials are beginning. Chemical reprogramming is moving from laboratory curiosity to medical reality, and the implications for human health and longevity are profound. We're not just treating disease anymore - we're rewriting biology itself, one cell at a time.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

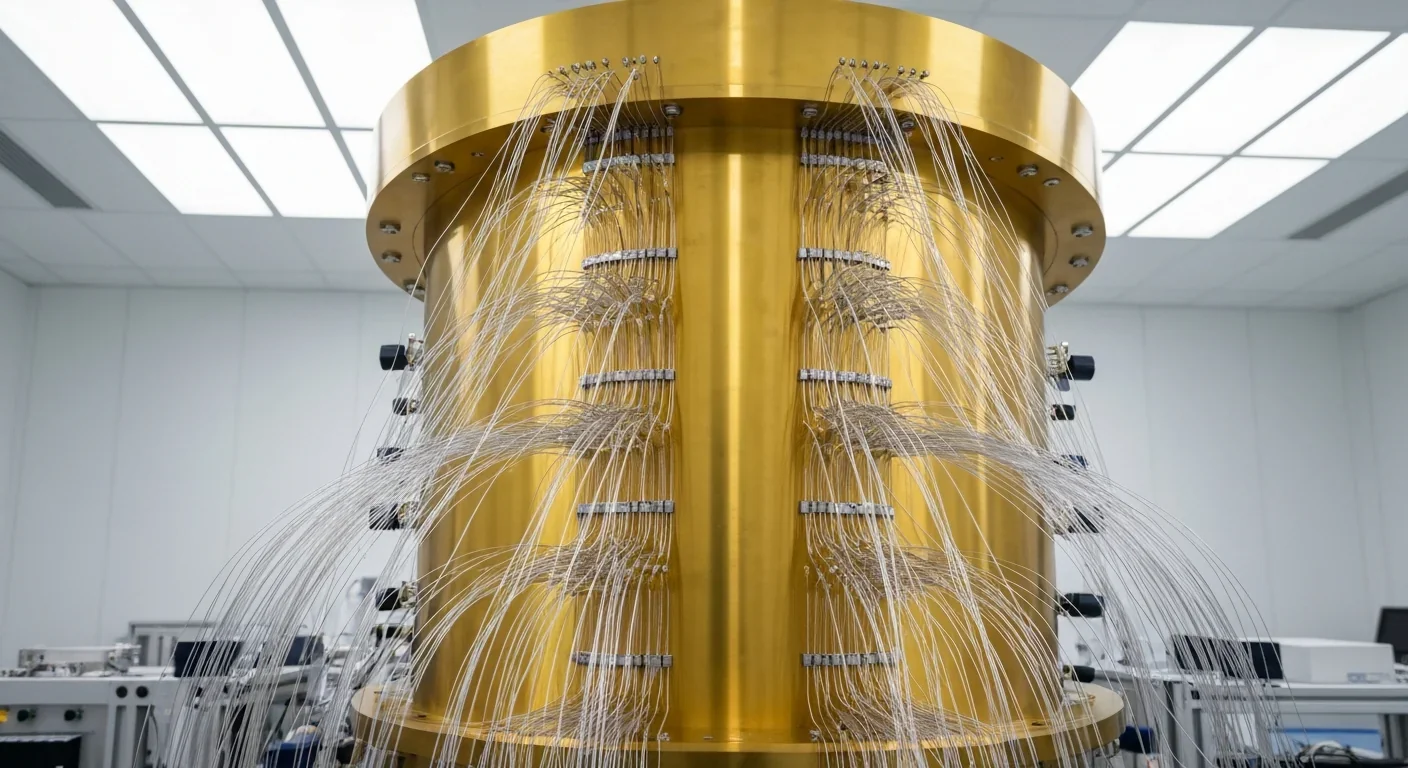

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.