Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: Hundreds of gut bacteria generate measurable electrical currents through extracellular electron transfer, potentially creating a bioelectric communication channel with the nervous system that operates alongside chemical gut-brain signaling.

Your gut is humming with electricity. Not metaphorically, but literally generating electrical currents strong enough to measure with an electrode. While scientists have spent decades mapping the chemical highways between your digestive system and your brain, they've discovered something far stranger: hundreds of bacterial species in your gut are producing electricity, and these bioelectric signals might be speaking directly to your nervous system.

This isn't speculative science fiction. Researchers at UC Berkeley measured the current streaming from common gut bacteria like Listeria monocytogenes and found it producing up to 500 microamps of electricity, pumping out roughly 100,000 electrons per second per cell. These microbes generate electricity through a process called extracellular electron transfer, essentially breathing electrons the way we breathe oxygen.

What makes this discovery revolutionary isn't just that bacteria make electricity. It's where they're doing it: in the human gut, home to trillions of microbes that have been implicated in everything from depression to Parkinson's disease. For years, scientists assumed the gut-brain axis operated solely through chemical messengers like serotonin and inflammatory cytokines. Now we're staring at an entirely different communication channel, one that operates at the speed of electricity rather than the pace of molecular diffusion.

The mechanism behind bacterial electrogenesis reads like molecular engineering. Certain bacteria have evolved specialized protein complexes that shuttle electrons from inside their cells to the outside world, a process known as extracellular electron transfer (EET). Think of it as a cellular conveyor belt for charged particles.

Here's what happens: when bacteria metabolize nutrients, they strip electrons from sugar molecules. Those electrons need somewhere to go. While most organisms use oxygen as their final electron dump, electrogenic bacteria have developed an alternative route. They export electrons through their cell walls to external acceptors, minerals in sediment, electrodes in lab equipment, or potentially, the tissue of their host.

Electrogenic bacteria pump out roughly 100,000 electrons per second per cell, generating measurable electrical currents of up to 500 microamps in laboratory conditions.

Research published in Nature identified two primary mechanisms. Gram-negative bacteria like Shewanella and Geobacter use protein nanowires, literal conductive filaments that extend from the cell surface like biological power cables. These bacterial nanowires can conduct electrons across distances thousands of times longer than the bacteria themselves.

Gram-positive bacteria, including many gut residents, employ a simpler strategy. They use flavin molecules, small organic compounds abundant in the gut environment, as electron shuttles. UC Berkeley's research showed that bacteria release flavins into their surroundings, where these molecules pick up electrons from the bacterial surface and ferry them to nearby acceptors. It's elegantly efficient, requiring no specialized appendages, just chemistry.

The discovery of flavin-mediated electron transfer in gut bacteria was particularly surprising. Scientists had focused on exotic bacteria living in oxygen-depleted sediments, species that respire minerals instead of oxygen. Nobody expected to find sophisticated electrical systems in ordinary gut microbes, organisms studied for decades without anyone noticing they were essentially tiny batteries.

Genomic surveys have revealed the extent of bacterial electrogenesis in the human gut. Over 100 species in the typical human microbiome possess the genetic machinery for extracellular electron transfer. This isn't a quirk of rare extremophiles; it's a widespread capability hidden in plain sight.

The roster includes familiar names. Listeria monocytogenes, the pathogen behind foodborne illness. Clostridium perfringens, responsible for gas gangrene and food poisoning. Enterococcus faecalis, a common gut resident that can become opportunistic in hospital settings. Lactobacillus species, the probiotic darlings sold in yogurt and supplements.

Even more intriguing, electrogenic capability cuts across bacterial lifestyles. It shows up in pathogens and beneficial commensals alike, in aerobic and anaerobic species, in bacteria that ferment sugars and those that respire other compounds. This evolutionary distribution suggests electron transfer serves multiple purposes beyond simple respiration.

"This is a whole big part of the physiology of bacteria that people didn't realize existed, and that could be potentially manipulated."

- Sam Light, Postdoctoral Fellow, UC Berkeley

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a notorious opportunistic pathogen, generates electricity through both direct contact electron transfer and soluble mediators like pyocyanin and pyorubrin. Researchers discovered that mutant strains with altered type IV pili, structures normally used for movement and surface adhesion, produced different electrical outputs. The pilT mutant, which has extended pili, generated higher currents than wild-type bacteria, suggesting these appendages do more than mechanical work.

This diversity raises a fundamental question: why is bacterial electricity so common? The simplest answer is energy. When oxygen runs low, which happens frequently in the gut's deeper layers, bacteria need alternative ways to dump electrons. But emerging evidence suggests they might also use electricity for communication.

The gut and brain are already known to communicate extensively. The vagus nerve provides a direct neural highway carrying signals between gut and brain. Chemical messengers like serotonin, produced abundantly in the gut, influence mood and cognition. Immune signals from gut inflammation can trigger brain responses. But electrical signaling adds an entirely new layer to this conversation.

Here's why it matters: neurons operate electrically. Your thoughts, movements, and sensations are encoded in electrical impulses propagating along nerve fibers. The enteric nervous system, sometimes called the "second brain," contains roughly 500 million neurons embedded in the gut wall. These neurons control digestion, but they also communicate extensively with the central nervous system.

Now consider that bacteria can produce electrical currents in the microenvironment where these neurons reside. Could bacterial electricity modulate neural activity? The evidence is mostly indirect, but suggestive.

Researchers have demonstrated that bacteria use electrical signals to coordinate behavior across long distances, recruiting distant cells through bioelectric pulses. These signals propagate through biofilms at speeds incompatible with chemical diffusion. If bacteria can electrically signal each other, the machinery exists for them to electrically signal host cells.

The interface between bacterial electricity and neural tissue remains speculative. Neurons respond to electrical fields. Even weak fields can alter firing patterns, synchronize activity, or modulate neurotransmitter release. Studies examining gut health and mood have established correlations between microbiome composition and mental health outcomes, but the mechanisms remain elusive. Could some of those effects flow through electrical channels rather than chemical ones?

One intriguing possibility involves the vagus nerve, which carries both chemical and electrical signals from gut to brain. Vagal afferents, nerve fibers that sense gut conditions, respond to mechanical stretch, chemical signals, and potentially electrical fields. If bacterial electrogenesis generates local electric fields in gut tissue, vagal neurons might detect those signals and relay information to the brain about the electrical state of the microbiome.

The hypothesis gains circumstantial support from research showing that vagus nerve stimulation, a therapeutic technique using electrical pulses, can reduce inflammation and alter mood. If external electrical stimulation affects gut-brain communication, internal electrical signals from bacteria might do the same.

Understanding bacterial electrogenesis required developing new measurement tools. Traditional microbiology focuses on growth, metabolism, and gene expression, not electrical output. Researchers adapted techniques from electrochemistry and bioengineering to probe microbial electricity.

Organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) represent one breakthrough. These devices use conducting polymers that change electrical properties when bacteria transfer electrons. By coupling bacteria to OECTs, researchers can translate microbial electron transfer into easily detectable electrical signals in real time.

New biosensors can detect bacterial electrical activity in under 20 minutes using paper-based devices that cost pennies to manufacture.

The method works by depositing bacteria onto a transistor gate coated with PEDOT:PSS, a conducting polymer. When electrogenic bacteria like Shewanella oneidensis transfer electrons, they reduce (de-dope) the polymer, changing the transistor's conductivity. The result is a biosensor that responds directly to bacterial electrical activity, enabling continuous monitoring rather than endpoint measurements.

Paper-based electrofluidic arrays offer another approach. These disposable sensors use conductive ink printed on paper to create miniature fuel cells powered by bacteria. A single sheet can test multiple bacterial strains simultaneously, with results appearing in under 20 minutes.

When researchers coated paper anodes with PEDOT:PSS, they reduced internal resistance from 800 kilohms to 200 kilohms and doubled power output to about 0.4 microwatts per square centimeter. The improvement came from enhanced bacterial adhesion and better electron transfer at the bacteria-electrode interface. This kind of engineering optimization suggests pathways toward implantable sensors that could monitor gut bacterial electricity in living subjects.

The measurement advances have practical implications beyond basic research. If bacterial electrogenesis influences health, detecting changes in electrical output could serve as an early warning system for dysbiosis, the microbial imbalance associated with inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, and mental health disorders.

The gut-brain axis has become a major focus in psychiatry and neuroscience. Studies link microbiome composition to depression, anxiety, autism spectrum disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's. Mechanisms have centered on neurotransmitter production, immune modulation, and metabolite signaling. Electrical signaling would add another dimension.

Consider the numbers: your gut contains roughly 100 trillion bacteria, many of them electrogenic. If each produces 100,000 electrons per second, the cumulative electrical output is staggering. While most of those electrons probably reduce local minerals or organic molecules, even a tiny fraction interacting with neural tissue could be physiologically significant.

Research modeling gut-brain bioelectrical signaling suggests that bacterial electrical activity could influence the enteric nervous system's firing patterns. Changes in the microbial community structure, which occurs in depression and anxiety, would alter the collective electrical field generated by the microbiome.

"It could tell us a lot about how these bacteria infect us or help us have a healthy gut."

- Dan Portnoy, Professor of Molecular and Cell Biology, UC Berkeley

The hypothesis connects to established findings. Probiotic supplementation with Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species has shown modest benefits for anxiety and depression in some studies. Both genera contain electrogenic species. Could their therapeutic effects involve electrical as well as chemical mechanisms?

Similarly, dietary interventions that alter microbiome composition, high-fiber diets rich in fermentable substrates, change both the bacterial community and its metabolic activity. If bacteria use electron transfer to metabolize complex carbohydrates, diet would directly modulate the gut's electrical environment.

The connection extends to inflammation, a known link between gut dysbiosis and mental health. Electrical signaling might modulate immune responses. Some research shows that weak electrical currents can reduce bacterial biofilm formation and antimicrobial resistance, suggesting electricity influences bacterial behavior in ways that affect host immunity.

If bacterial electricity influences the gut-brain axis, therapeutic interventions become possible. The concept of "electroceuticals," treatments using electrical stimulation rather than drugs, has gained traction in medicine. Pacemakers for the heart, deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's, and vagus nerve stimulation for depression all demonstrate that electrical therapies work.

Microbial electroceuticals could operate differently. Instead of external devices delivering current, engineered bacteria could generate targeted electrical signals in situ. Researchers have already demonstrated proof-of-concept by incorporating genetic circuits into electrogenic bacteria, creating cells that adjust electrical output in response to specific chemical signals.

The approach uses synthetic biology. Scientists insert DNA circuits into bacteria, programming them to detect environmental cues like inflammation markers or pH changes and respond by modulating electron transfer. Coupled to biosensing electronics, these engineered microbes could function as living diagnostic tools, reporting gut conditions through electrical signals picked up by implanted sensors.

Therapeutic applications might involve colonizing the gut with designer bacteria that produce specific electrical patterns. Imagine probiotic strains engineered to generate currents that reduce anxiety by modulating vagal nerve activity, or that suppress inflammation by electrically influencing immune cells.

The technology isn't ready for clinical use. We don't fully understand how bacterial electricity affects human physiology, what electrical patterns are therapeutic versus harmful, or how to safely introduce and control engineered microbes in the gut. But the fundamental components exist: electrogenic bacteria, genetic engineering tools, and implantable bioelectronics.

Microbial fuel cell research has explored using bacterial electricity for power generation. While harvesting energy from gut bacteria sounds far-fetched, similar principles could power implanted medical devices. A pacemaker or neural stimulator running on microbial fuel would never need battery replacement.

More immediately practical are diagnostic applications. Wearable or implantable sensors that monitor gut bacterial electrical activity could track microbiome health continuously, alerting patients and physicians to dysbiosis before symptoms appear. Changes in electrical signatures might predict inflammatory bowel disease flares, guide dietary interventions, or monitor response to antibiotics.

Despite rapid advances, electromicrobiology remains in its infancy. Most research has focused on model organisms in laboratory conditions, not complex microbial communities in living hosts. The gap between bacterial electricity measured on an electrode and its effects in gut tissue is vast and largely unexplored.

Key questions remain unanswered. What fraction of bacterial electron transfer in the gut actually generates electrical currents versus reducing local molecules? Do bacterial electrical signals reach neural tissue, or are they absorbed by the surrounding environment? How do different electrogenic species interact electrically; can they amplify, interfere with, or coordinate their outputs?

Over 100 bacterial species in your gut have the genetic machinery to produce electricity, yet we still don't know what most of this electrical activity actually does in the living body.

The temporal dynamics are unclear. Bacteria generate electrical currents continuously while metabolizing, but does this create a steady background field or fluctuating signals? If it fluctuates, what are the relevant timescales? Neurons fire on millisecond timescales, while bacterial growth and metabolism occur over minutes to hours. Matching these rhythms, or lack thereof, matters for understanding potential neural effects.

Spatial organization adds complexity. The gut isn't a uniform environment. Bacterial density, oxygen levels, and nutrient availability vary dramatically from the intestinal lumen to the mucosal surface. Electrogenic bacteria concentrate in specific niches. Do those niches position them to interact with neural tissue, or are they electrically isolated?

Individual variation presents another challenge. Each person's microbiome is unique, shaped by genetics, diet, environment, and medical history. Does this translate to unique electrical signatures? Could differences in gut bacterial electricity contribute to individual differences in mood, cognition, or disease susceptibility?

The field also lacks standardized methods. Different labs measure bacterial electricity using different techniques, electrodes, growth conditions, and data analysis approaches. Comparing results across studies is difficult. The Center for Electromicrobiology at Aarhus University is working to establish standards and collaborative frameworks, but much work remains.

The discovery of widespread bacterial electrogenesis in the gut opens new research directions. Scientists are beginning to map which bacteria are electrogenic, under what conditions they produce electricity, and how electrical activity relates to bacterial community function.

Advanced techniques in electron transfer research recently revealed the molecular machinery bacteria use to assemble nanowire structures essential for long-range electron transfer. This ancient mechanism, conserved across diverse bacterial lineages, suggests electrogenesis played a crucial role in microbial evolution.

Understanding this machinery could enable genetic screens to identify new electrogenic species, predict electrical capabilities from genome sequences, or engineer bacteria with enhanced or suppressed electrogenesis. Such tools would accelerate research and enable more sophisticated experimental designs.

Large-scale studies correlating gut electrical signatures with health outcomes could reveal whether bacterial electricity is a meaningful health biomarker. Technologies like metagenomic sequencing can identify which bacteria are present; coupling that with electrical measurements could show which are electrically active in different health states.

Animal models will be crucial. Germ-free mice colonized with defined bacterial communities allow controlled experiments. Researchers could introduce electrogenic versus non-electrogenic strains and measure effects on behavior, gut motility, immune function, and neural activity. Such experiments could establish causal links between bacterial electricity and physiological outcomes.

Ultimately, understanding the electrical dimension of the microbiome might transform how we think about gut-brain communication. The chemical paradigm, bacteria produce neurotransmitters and metabolites that influence the brain, has been productive but incomplete. Adding electrical signaling creates a more comprehensive picture, one where the microbiome communicates through multiple channels simultaneously.

For now, the practical implications are limited. We can't yet measure your gut's electrical activity in a clinic, can't diagnose diseases based on bacterial electricity, and can't prescribe treatments targeting microbial electrogenesis. But the trajectory is clear.

Within the next decade, gut electrical monitoring could become routine. Wearable sensors or capsule endoscopes equipped with micro-electrodes might track your microbiome's electrical signature, providing personalized insights into gut health. Changes in electrical patterns could prompt dietary adjustments or probiotic interventions before problems escalate.

The probiotic industry, already marketing bacteria for mental health, might shift toward electrically-optimized strains. Rather than focusing solely on neurotransmitter production, next-generation probiotics could be selected or engineered for specific electrical outputs believed to support mood, reduce inflammation, or enhance gut barrier function.

Dietary recommendations might evolve to consider effects on bacterial electrogenesis. Certain nutrients, particularly those bacteria use for electron transfer like riboflavin and other B vitamins, could be emphasized. Foods that promote electrogenic species might be recommended for specific conditions.

The bigger picture involves reconceptualizing the human body as a bioelectric system where microbial and human components interact through both chemical and electrical signals. Your thoughts might be influenced not just by neurotransmitters your gut bacteria make, but by the electrical currents they generate.

This isn't to suggest bacteria control your mind through electricity. The effects, if they exist, are likely subtle modulations rather than direct control. But subtle doesn't mean insignificant. Mood, cognition, and behavior emerge from complex interactions among billions of neurons. Small changes to neural excitability or network dynamics can have meaningful consequences.

As we learn more, the boundary between "you" and your microbiome becomes more porous. These bacteria aren't just passengers or even partners; they're electrically active participants in your nervous system's operation. The implications reach from fundamental neuroscience to personalized medicine to philosophical questions about biological identity.

The shock of discovering gut bacteria generate electricity is wearing off, replaced by harder questions. What does all this electricity do? How much matters for health? Can we harness it therapeutically?

Research is accelerating. New tools for studying bacterial electricity emerge regularly, each enabling experiments previously impossible. The field attracts researchers from microbiology, neuroscience, bioengineering, and medicine, creating productive collisions between disciplines.

Clinical trials are still years away, but preclinical work is advancing. Studies in animals will establish whether microbial electricity meaningfully affects neural function, immune responses, and disease outcomes. If the effects are real and substantial, human trials will follow.

The path from basic discovery to clinical application is long and uncertain. Many promising findings in microbiome research have failed to translate into effective therapies. The hype around probiotics, fecal transplants, and microbiome-based diagnostics has sometimes exceeded the evidence. Skepticism is warranted.

But the electrical dimension of the microbiome represents something genuinely new. It's not just another chemical pathway or metabolic function. It's a different mode of communication, one that operates at neural timescales and might interface directly with the nervous system. That novelty creates unique opportunities.

If bacterial electricity does influence the gut-brain axis, it could explain why microbiome interventions sometimes work when chemical mechanisms alone don't fully account for the effects. It might reveal why individual responses to probiotics vary so dramatically. It could point toward combination therapies that address chemical, immune, and electrical aspects of gut-brain communication simultaneously.

The electric microbiome is no longer science fiction. It's documented, measurable, and widespread. What we do with that knowledge will define the next chapter of both microbiology and neuroscience. Your gut is humming with electricity, and we're only beginning to understand what it's saying.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

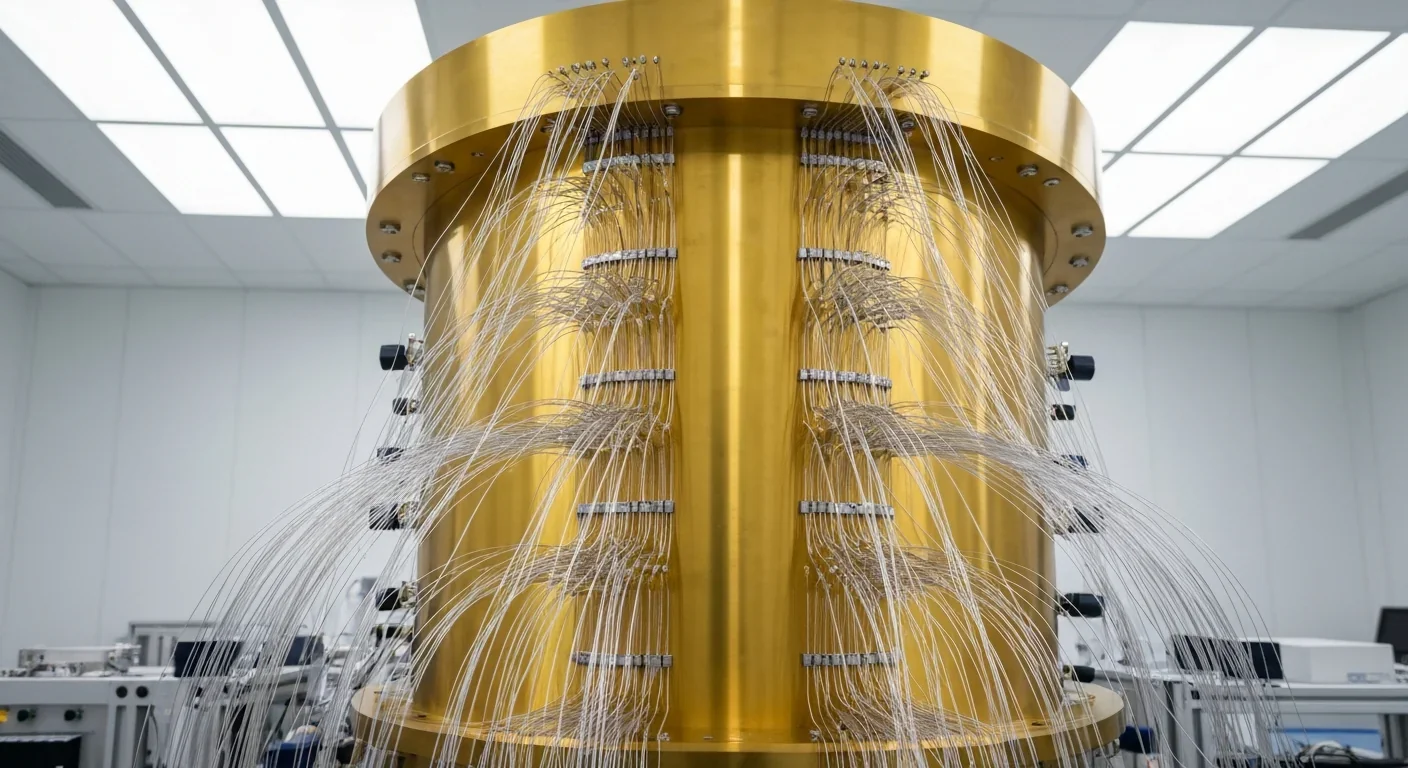

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.