Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: Spatial transcriptomics maps exactly where genes activate within tissues, transforming drug discovery by revealing how diseases organize spatially. The technology is accelerating pharmaceutical research, advancing precision medicine, and reshaping our understanding of cancer, neurological conditions, and human biology.

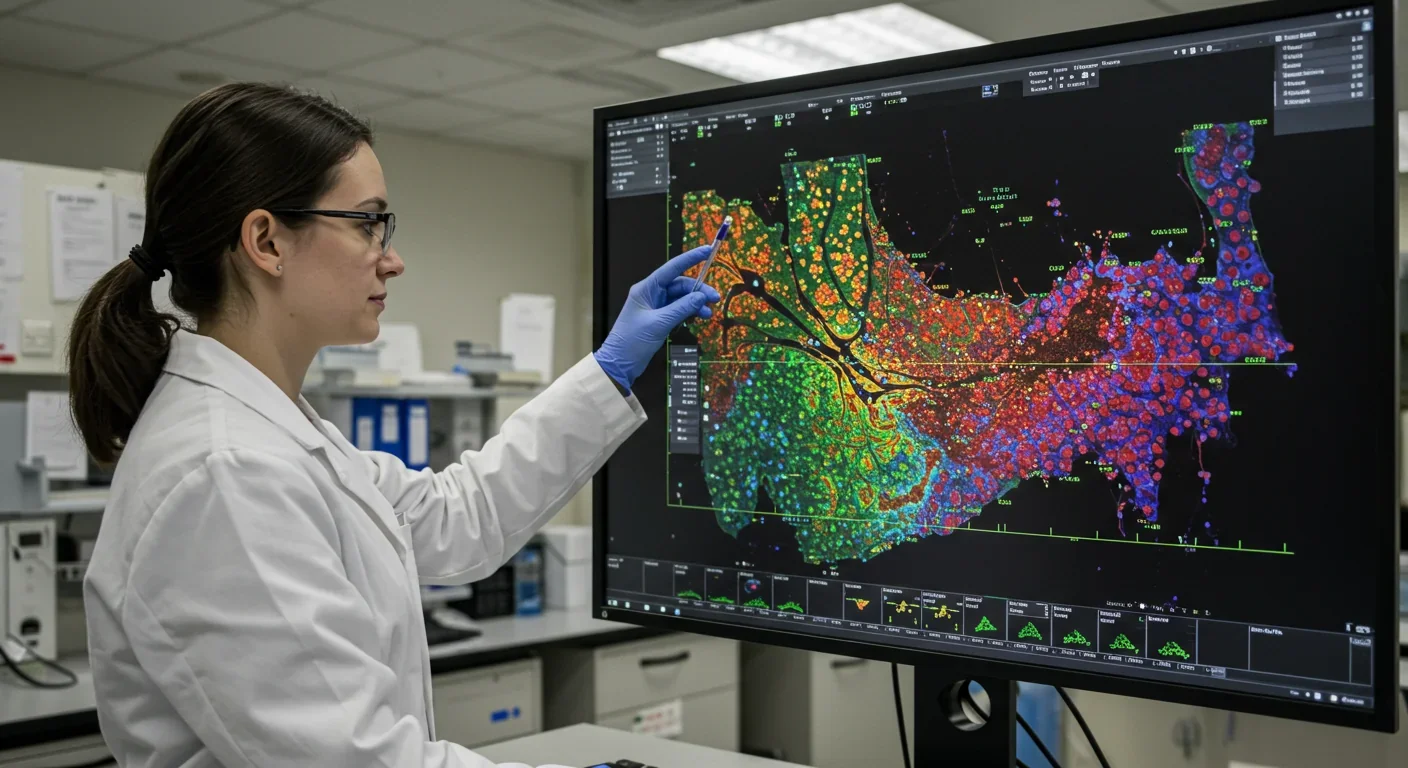

For decades, scientists could tell you which genes were active in a tissue sample, but they couldn't tell you where. It's like knowing a city has restaurants, hospitals, and schools, but having no map to find them. That changed when researchers developed spatial transcriptomics, a technology that combines gene sequencing with precise spatial coordinates to create molecular atlases of tissues. Now, pharmaceutical companies can pinpoint exactly where disease processes begin, where tumors develop treatment resistance, and where therapeutic interventions should target. The result is accelerating drug discovery from years to months and transforming how we understand human biology at its most fundamental level.

The breakthrough solves a problem that's plagued biomedical research since genomics began. Traditional sequencing methods grind tissues into a homogeneous soup, destroying all spatial relationships between cells. It's like blending a newspaper and trying to reconstruct the articles. Spatial transcriptomics preserves tissue architecture while reading the genetic activity of every cell, revealing how neighboring cells communicate, how disease spreads through tissue, and where therapeutic vulnerabilities hide.

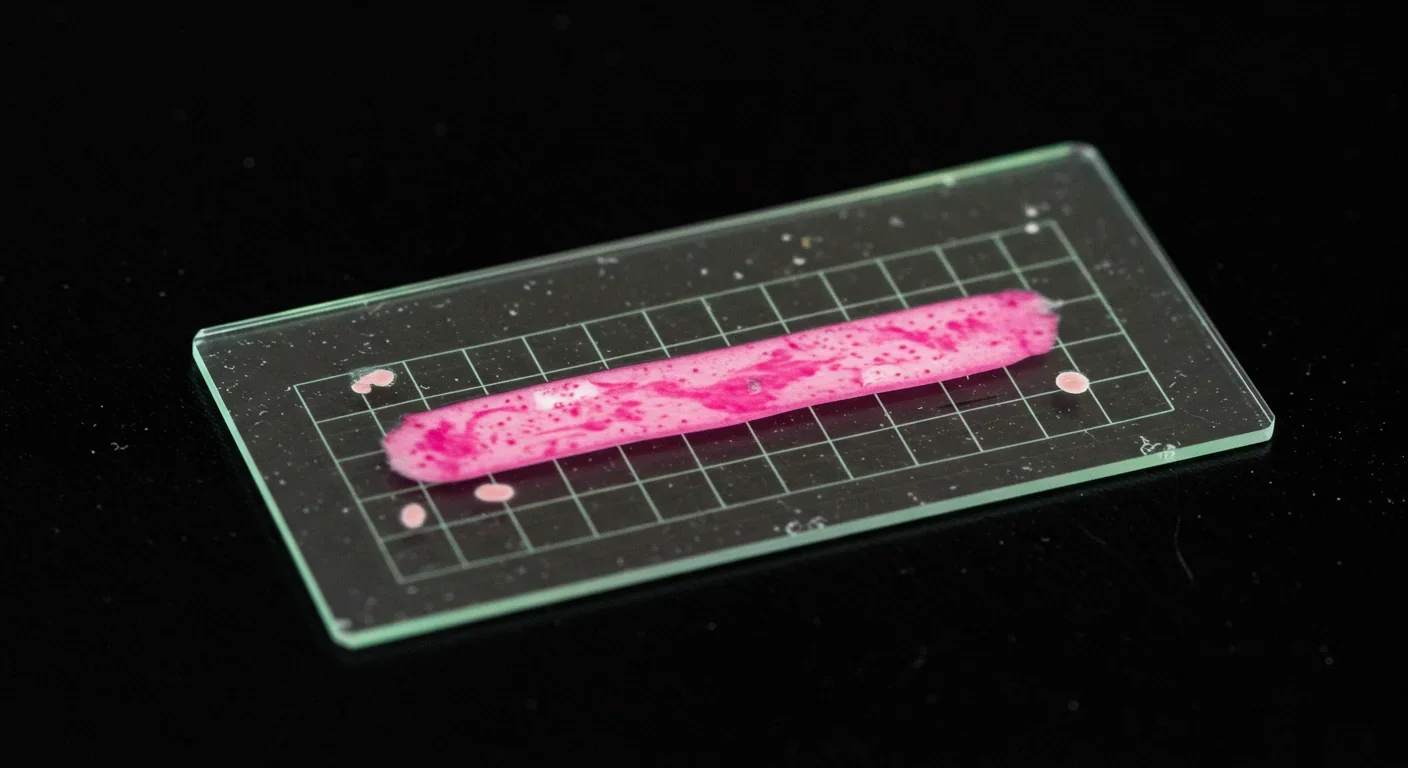

The technology works by placing thin tissue slices onto specially designed slides covered with millions of capture probes bearing unique spatial barcodes. When cells release their RNA molecules, these probes grab them and tag them with location coordinates. Scientists then sequence these barcoded molecules, matching each gene's activity to its precise position in the tissue. The result is a high-resolution map showing not just what genes are doing, but exactly where they're doing it.

Modern platforms achieve subcellular resolution, meaning they can distinguish gene activity within different parts of a single cell. That level of detail matters enormously because cells in different tissue regions behave differently, even if they're genetically identical. A liver cell near a blood vessel has different responsibilities than one deep in the organ. Understanding these spatial patterns reveals how tissues organize themselves and how diseases disrupt that organization.

Several competing technologies have emerged, each with different trade-offs between resolution, gene coverage, and cost. Visium from 10x Genomics offers whole-transcriptome coverage at moderate resolution. MERFISH uses combinatorial fluorescent barcoding to achieve higher resolution while measuring hundreds of genes simultaneously. GeoMx Digital Spatial Profiler lets researchers select specific tissue regions for deep analysis. CosMx can measure up to 6,000 genes with subcellular precision across entire tissue sections.

Genomics has always had a blind spot. When the Human Genome Project completed in 2003, it gave us a parts list for human biology but no assembly instructions. Scientists could identify disease-associated genes but couldn't determine where those genes mattered most. It's the difference between knowing a building has faulty wiring somewhere versus knowing exactly which wall to open.

Single-cell RNA sequencing, developed in the 2010s, provided finer resolution by profiling individual cells, but it still destroyed spatial context. Researchers lost information about which cells were neighbors, how tissues were organized, and where disease boundaries existed. That limitation became increasingly problematic as evidence mounted that location drives cell behavior as much as genetics does.

Traditional sequencing destroys spatial relationships between cells - it's like blending a newspaper and trying to reconstruct the articles. Spatial transcriptomics preserves the tissue architecture that determines how cells actually function.

The first spatial transcriptomics method emerged from the laboratory of Joakim Lundeberg at Sweden's Royal Institute of Technology in 2016. His team developed a technique to capture RNA molecules on barcoded slides, preserving their spatial coordinates. The approach won the Method of the Year award from Nature Methods in 2020, triggering an explosion of innovation as companies raced to improve resolution, scale, and accessibility.

What followed resembles the early days of DNA sequencing, when competing technologies battled for dominance. Imaging-based methods like MERFISH and seqFISH achieved high spatial resolution by directly visualizing RNA molecules in intact tissue. Sequencing-based methods like Visium offered broader gene coverage but lower resolution. Hybrid approaches attempted to combine the best of both worlds. The field has converged toward platforms that balance resolution, throughput, and cost for specific applications.

Today's spatial transcriptomics platforms vary dramatically in their capabilities. At one end, Visium HD achieves bin sizes as small as 2 micrometers, approaching single-cell resolution while measuring the entire transcriptome. At the other, targeted panels measure hundreds of carefully selected genes with subcellular precision. The choice depends on whether you need comprehensive discovery or focused validation.

Resolution isn't just about seeing smaller features. It's about capturing biological reality. Tumors aren't uniform masses but complex ecosystems where cancer cells, immune cells, blood vessels, and connective tissue interact. High-resolution spatial transcriptomics reveals these interactions, showing how cancer cells shield themselves from immune attack or where blood vessels feed tumor growth. That spatial architecture often determines whether a cancer responds to treatment.

MERFISH 2.0 represents the current state of the art in imaging-based approaches. It uses error-robust barcoding to maintain accuracy even when measuring thousands of genes simultaneously. The system works by encoding each gene's identity in a unique pattern of fluorescent labels, then cycling through multiple rounds of imaging to read those patterns. Because it images intact tissue, it captures subcellular details that sequencing-based methods miss.

Sequencing-based methods excel at unbiased discovery. When you don't know which genes matter, measuring everything gives you the best chance of finding them. Recent advances have dramatically improved these platforms' resolution. Visium HD divides tissue into bins containing just a few cells, while still profiling tens of thousands of genes. That combination of breadth and resolution makes it ideal for exploratory studies.

"Spatial multi-omics platforms measure RNA, proteins, and small molecules simultaneously, providing the molecular context needed to understand how gene expression translates into cellular function in real tissues."

- Frontiers in Immunology, 2025

The newest frontier combines spatial transcriptomics with proteomics and metabolomics. Spatial multi-omics platforms measure RNA, proteins, and small molecules simultaneously, providing richer molecular context. Proteins often matter more than RNA for drug targeting, since they're the actual functional molecules. Measuring both in the same spatial context reveals how gene expression translates into cellular function.

Major pharmaceutical companies have made spatial transcriptomics central to their drug discovery operations. The technology addresses a critical bottleneck: most drug candidates fail because they don't work in the complex spatial environment of real tissues. Testing compounds on cells in a dish can't predict how they'll behave when those cells are organized into functional organs surrounded by blood vessels, immune cells, and structural support.

Outsourcing to specialized service providers has democratized access to spatial transcriptomics. Smaller biotech firms and academic labs that can't afford expensive equipment can now send tissue samples to companies that run the analyses and return the data. This model mirrors how DNA sequencing became accessible, lowering barriers to entry and accelerating adoption across the research community.

The cost structure has improved dramatically. Early spatial transcriptomics experiments cost thousands of dollars per sample, limiting their use to well-funded projects. Today, bulk discounts and automation have pushed costs below $1,000 per sample for many platforms, with some targeted panels running even cheaper. That makes spatial profiling viable for routine use rather than just flagship studies.

Integration with existing drug discovery workflows required more than just technological maturity. Pharma companies needed to train scientists in spatial data analysis, develop computational pipelines for processing massive datasets, and create protocols for incorporating spatial insights into target validation and clinical trial design. Those infrastructures are now in place at most major pharmaceutical companies.

The speed advantage matters enormously in competitive drug development. Spatial transcriptomics can identify which patients will respond to a therapy in weeks instead of months, guide combination therapy selection, and reveal why treatments fail in resistant patients. That acceleration compresses development timelines and gets effective drugs to patients faster.

Cancer research has been transformed by spatial transcriptomics more than any other field. The technology revealed that tumors organize themselves into distinct spatial neighborhoods where different cell types concentrate. Some regions exclude immune cells, creating "cold" zones where immunotherapy can't work. Others have abundant blood vessels that feed tumor growth. Mapping these spatial patterns predicts treatment response and identifies combination therapies that might overcome resistance.

One striking discovery involves the tumor microenvironment's role in drug resistance. Spatial transcriptomics showed that cancer cells near blood vessels express different genes than those deeper in the tumor, making them more resistant to chemotherapy. That spatial gradient explains why tumors shrink initially but then regrow from surviving cells in protected locations. Targeting both the cancer cells and their protective niches offers a way to achieve more durable responses.

Tumors aren't uniform. Spatial transcriptomics reveals that cancer cells organize into neighborhoods with distinct molecular signatures - some exclude immune cells, others cluster near blood vessels. These spatial patterns determine whether treatments work or fail.

Neurological disease research has gained equally profound insights. Alzheimer's disease studies using spatial transcriptomics identified specific brain regions where disease processes begin, how pathology spreads between neighboring cells, and which cell types are most vulnerable. That spatial understanding guides development of therapies targeting early disease stages before widespread damage occurs.

Brain mapping projects are using spatial transcriptomics to create comprehensive atlases of neural organization. These maps reveal how different neuron types organize into functional circuits, how brain regions communicate, and how diseases disrupt those communication patterns. The Allen Brain Atlas, one of the most ambitious such projects, combines spatial transcriptomics with other imaging modalities to build a complete molecular map of the human brain.

Cardiovascular research discovered something unexpected: neuro-immune interactions in heart tissue play crucial roles in heart disease. Spatial transcriptomics mapped how nerve fibers and immune cells interact spatially, revealing signaling pathways that regulate inflammation after heart attacks. Targeting those interactions might reduce damage and improve recovery.

Infectious disease researchers are using spatial transcriptomics to understand how pathogens interact with host tissues. COVID-19 studies mapped where the virus infects different lung cell types, how infection spreads to adjacent cells, and how the immune response organizes spatially. That information guides development of therapies that block viral spread or modulate harmful immune responses.

The spatial genomics market has exploded from essentially nothing in 2016 to a projected $1.2 billion in 2025, with analysts forecasting growth to $7.5 billion by 2035. That expansion reflects both falling costs and rising demand as more researchers recognize spatial information's value. Equipment manufacturers, service providers, and software companies have all emerged to serve this growing market.

Market dynamics favor consolidation around a few major platforms. 10x Genomics dominates the sequencing-based segment with its Visium platform, while NanoString and Vizgen compete in the imaging-based space. Smaller companies target specialized niches like ultra-high-resolution imaging or spatial proteomics. Mergers and acquisitions have been frequent as larger firms acquire innovative technologies.

The business model is evolving beyond instrument sales toward recurring revenue from consumables, services, and software. Each spatial transcriptomics experiment requires specialized slides, reagents, and computational analysis, creating ongoing revenue streams. Cloud-based analysis platforms charge subscription fees for storing and processing the massive datasets these experiments generate.

Investment in spatial biology infrastructure has become a competitive necessity for pharmaceutical companies. Those without in-house capabilities risk falling behind competitors who can select better drug targets and predict clinical success more accurately. That pressure is driving adoption even as companies wait for costs to fall further.

The United States currently leads in spatial transcriptomics innovation, with major technology companies clustered in the Bay Area and Boston. But Europe and Asia are catching up rapidly. Sweden's Karolinska Institute, birthplace of the original spatial transcriptomics method, remains a major research hub. China has made massive investments in spatial biology, with companies like BGI developing competitive platforms at lower price points.

International collaboration has been crucial for creating comprehensive spatial atlases of human tissues. The Human Protein Atlas project, led by Swedish researchers, combines spatial transcriptomics with immunohistochemistry to map where every protein is expressed in the human body. Similar international efforts are building spatial atlases of the brain, heart, immune system, and other organ systems.

"Different regulatory environments are creating divergent timelines for clinical adoption. Europe's more receptive approach to spatial profiling for treatment selection means some applications will reach patients there first."

- Drug Discovery World, 2024

Different regulatory environments affect how quickly spatial transcriptomics can move from research to clinical diagnostics. European regulators have been more receptive to spatial profiling for guiding treatment selection, while US regulators demand extensive validation. That regulatory divergence creates different adoption timelines across regions and incentivizes companies to pursue approval in more permissive jurisdictions first.

Intellectual property battles have erupted as companies race to patent key spatial transcriptomics innovations. The high stakes reflect expectations that spatial profiling will become standard practice in drug development and clinical diagnostics. Companies that control essential patents will be able to extract licensing fees from the entire industry.

Despite rapid progress, spatial transcriptomics faces significant hurdles before it can become routine in clinical practice. The technology still requires fresh or carefully frozen tissue samples, limiting its use to research settings where sample quality can be controlled. Clinical biopsies often sit at room temperature for hours before processing, degrading RNA and making spatial analysis difficult or impossible.

Computational analysis remains a bottleneck. Each spatial transcriptomics experiment generates gigabytes or terabytes of data that must be processed, aligned to reference atlases, and analyzed for biological patterns. Deep learning models are helping automate this analysis, but they require extensive training data and expertise to use correctly. Many hospitals and clinics lack the computational infrastructure to handle these analyses.

Standardization is another major challenge. Different spatial transcriptomics platforms generate data in different formats, making it difficult to compare results across studies or combine datasets. The field needs common data standards, reference tissues, and quality metrics so that results from different labs can be integrated and validated.

The question of clinical utility remains partly unanswered. While spatial transcriptomics clearly provides valuable research insights, proving that it improves patient outcomes in clinical trials is harder. Does knowing the spatial organization of a patient's tumor actually lead to better treatment selection? Ongoing studies are addressing this question, but definitive answers require large, expensive trials.

Interpretation is a human challenge as much as a technical one. Spatial transcriptomics reveals enormous complexity in tissue organization, but scientists are still learning what all those patterns mean. Not every spatial signature has a clear biological interpretation. Distinguishing meaningful patterns from noise requires expertise that many researchers are still developing.

The next generation of spatial transcriptomics technologies will achieve subcellular resolution while measuring complete transcriptomes, eliminating the current trade-off between spatial precision and molecular coverage. These platforms will resolve individual organelles, synapses, and cellular microenvironments, bridging the gap between single-cell biology and tissue-level organization.

AI integration will accelerate analysis and interpretation. Machine learning models are being trained to recognize spatial patterns associated with disease, predict treatment response, and generate hypotheses about cell-cell interactions. Eventually, these systems may convert spatial transcriptomics data into automated diagnostic reports, potentially matching or exceeding human pathologists' accuracy.

Clinical applications are moving beyond research into diagnostics and treatment selection. Spatial profiling of tumor biopsies could soon guide personalized cancer treatment, identifying which patients will respond to immunotherapy or predicting drug resistance before it emerges. Similar applications are in development for autoimmune diseases, transplant rejection, and infectious diseases.

Integration with other spatial omics technologies will provide more complete molecular pictures. Combining spatial transcriptomics with spatial proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics in the same tissue section will reveal how different molecular layers interact spatially. That comprehensive view will be essential for understanding complex diseases and developing effective interventions.

The democratization trend will continue as costs fall and automation increases. Within a few years, spatial transcriptomics may become as routine as immunohistochemistry is today, with pathology labs routinely profiling tissue samples to guide treatment decisions. That shift will require new training programs, reimbursement structures, and quality standards, but the trajectory is clear.

What happens when spatial profiling becomes ubiquitous? We'll gain the ability to diagnose diseases earlier by detecting subtle spatial disorganization before symptoms appear. We'll design drugs that target specific tissue regions rather than bluntly affecting entire organs. We'll understand biological development and aging as spatial transformation processes, revealing intervention points we can't currently see. The future of medicine will be spatial, and that future is arriving faster than most people realize.

The technology is already revealing how little we actually understood about tissue organization and disease progression. Every spatial transcriptomics study uncovers unexpected patterns, challenging assumptions about how biology works. As these tools become more powerful and accessible, they'll continue rewriting our understanding of life's fundamental processes. The question isn't whether spatial biology will transform medicine, but how quickly we can build the infrastructure, expertise, and clinical evidence to realize its full potential.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

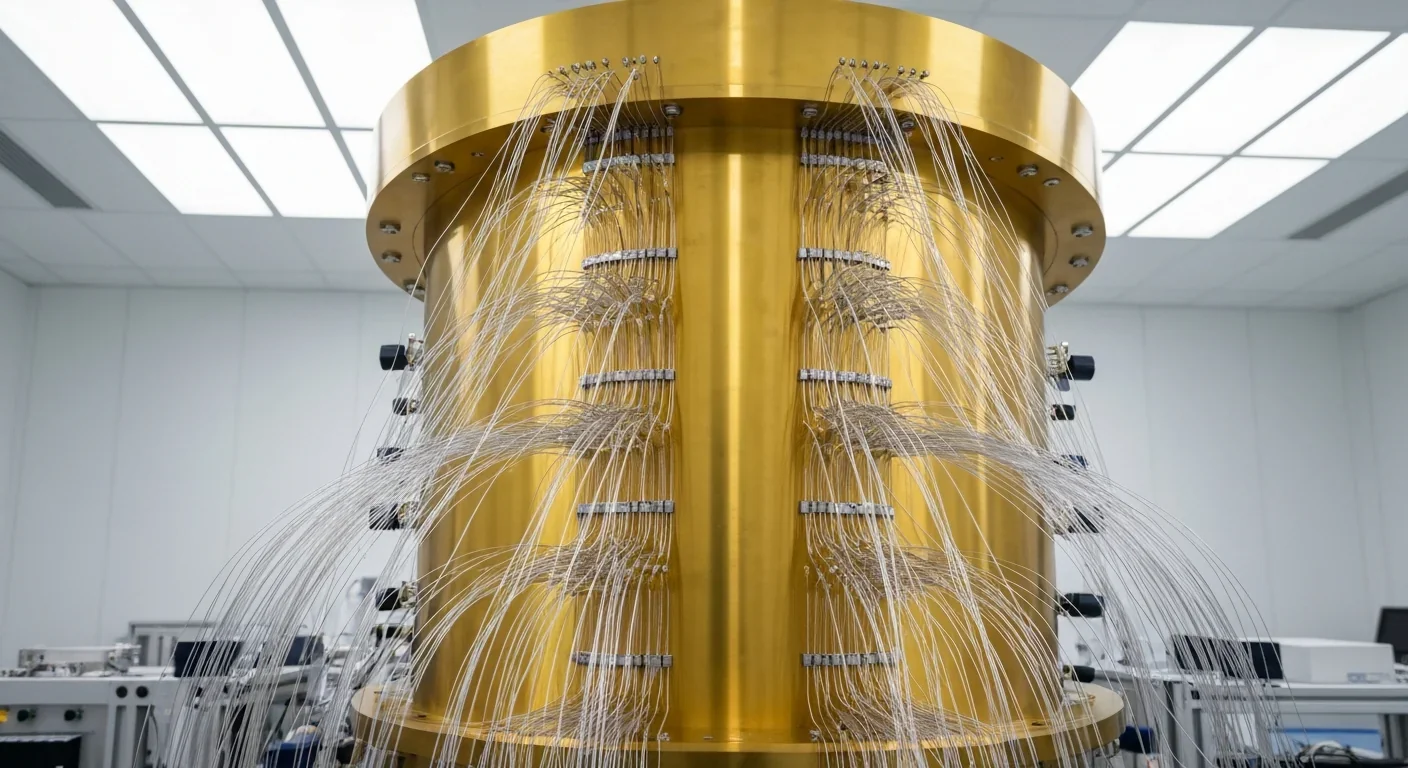

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.