Antibacterial Soap May Be Destroying Your Gut Health

TL;DR: CAR-T therapy genetically reprograms patients' immune cells to hunt cancer with remarkable success in blood cancers, achieving 50% remission in lymphoma and 80-90% in leukemia, though challenges remain with costs exceeding $1 million and limited effectiveness against solid tumors.

Within the next decade, the word "cure" might stop being a whisper in cancer wards and become something doctors can say out loud. We're already seeing patients walk out of hospitals five years after a single treatment, their blood cancers gone, with researchers cautiously using that forbidden C-word. This isn't chemotherapy's shotgun approach or radiation's scorched-earth strategy. This is something fundamentally different: turning your own immune cells into precision-guided weapons that hunt cancer with relentless focus.

CAR-T cell therapy, or chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, represents one of medicine's most audacious gambits: extracting immune cells from a patient's body, genetically reprogramming them in a lab to recognize cancer, multiplying them into an army numbering in the hundreds of millions, then infusing them back to seek and destroy malignant cells. It sounds like science fiction, but thousands of patients have already received this treatment, and the results are forcing oncologists to reconsider what's possible in cancer care.

Your immune system already has T cells designed to identify and eliminate threats, but cancer cells are maddeningly good at hiding. They disguise themselves as normal tissue, suppressing immune responses and slipping past your body's defenses. Traditional T cells often can't recognize them or, when they do, lack the firepower to mount an effective assault.

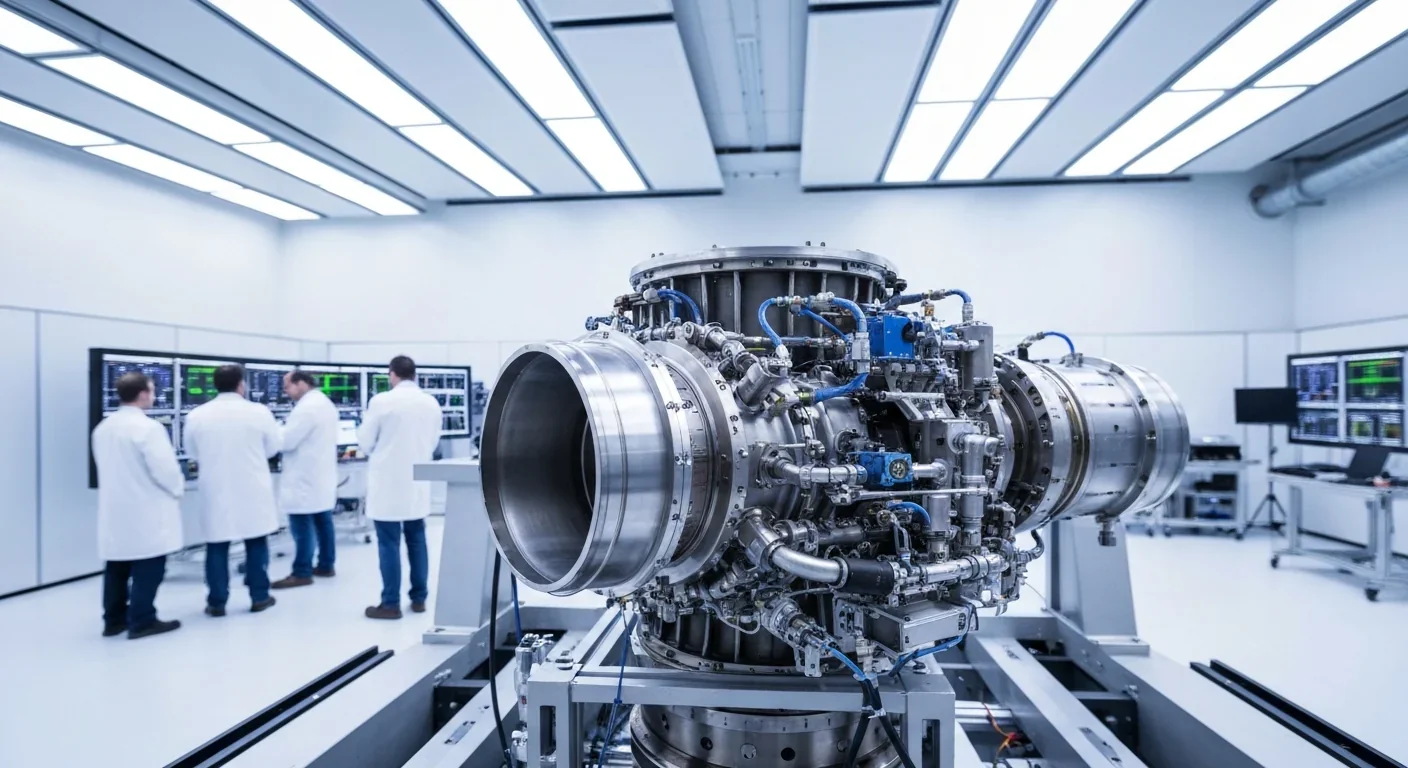

CAR-T therapy solves this problem through genetic engineering. Scientists extract T cells from a patient's blood through a process called leukapheresis, which takes several hours and feels similar to donating plasma. These cells then travel to a specialized manufacturing facility where technicians use a disabled virus to deliver new genetic instructions. The engineered gene codes for a chimeric antigen receptor, a synthetic molecule that sits on the T cell's surface like a radar dish tuned to detect specific proteins found on cancer cells.

The chimeric antigen receptor is a synthetic molecule that acts like a radar dish on T cells, locking onto specific proteins on cancer cells and triggering an immediate attack response.

The most common target is CD19, a protein abundant on the surface of B-cell lymphomas and leukemias. When a CAR-T cell encounters a cell displaying CD19, the receptor locks on, triggering the T cell to release toxic proteins that punch holes in the cancer cell's membrane. The cancer cell dies. The CAR-T cell survives, multiplies, and continues hunting for more targets.

This manufacturing process takes three to four weeks. During that time, patients often receive bridging chemotherapy to keep their cancer in check. When the engineered cells return, now numbering anywhere from hundreds of millions to billions, they're infused back into the patient's bloodstream through a simple IV line. Then the waiting begins.

The results from early CAR-T trials shocked even the researchers conducting them. For diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, one of the most common and aggressive blood cancers, about 50% of patients achieve complete remission at three months after receiving CD19-targeted CAR-T cells as a second- or third-line treatment. Many of those remissions prove durable, lasting years.

In acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the initial response rates are even more dramatic: 80-90% of patients enter remission. The challenge here is relapse. About half of these patients see their cancer return within 12 months, often because some leukemia cells don't express CD19 or lose the protein after treatment, making them invisible to the engineered T cells.

"We're finally at a point where we're seeing long-term outcome data for patients treated with CAR T cells and a subset are still in remission after a single treatment, with some patients even being called 'cure.'"

- University of Colorado Cancer Center

We're now five years out from the earliest patient treatments, and a subset of those people remain in remission with no additional therapy. Their doctors are starting to use the word "cure" in conversations, though always carefully, always with caveats. In oncology, where victories are often measured in months of progression-free survival, patients walking around healthy five years after a single treatment represents a paradigm shift.

These outcomes compare favorably to traditional options for relapsed or refractory blood cancers. Standard chemotherapy regimens for relapsed lymphoma typically achieve complete remission in only 20-30% of patients, with even fewer maintaining long-term disease control. Stem cell transplantation, the previous gold standard for these patients, carries significant risks and requires finding a matched donor, a process that can take months patients might not have.

CAR-T therapy was initially approved as a third-line treatment, reserved for patients who had already failed two other approaches. It's now moving up to second-line for certain lymphomas, especially for high-risk patients who relapse after initial treatment. Researchers are investigating its use even earlier, potentially as a first-line option for patients with particularly aggressive disease.

But not everyone qualifies. Patients need adequate organ function to survive the treatment's potential side effects. Their cancer must express the target protein, typically CD19 or BCMA for multiple myeloma. They must be healthy enough to undergo leukapheresis and withstand the intense immune response that follows CAR-T infusion. Patients with active infections, severe cardiac issues, or certain autoimmune conditions may not be candidates.

The eligibility criteria also depend on cancer type. Currently, the FDA has approved CAR-T therapies for several blood cancers: certain types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children and young adults, multiple myeloma, and mantle cell lymphoma. Solid tumors remain largely out of reach, though research is advancing rapidly.

Age isn't necessarily a barrier. Both children and adults in their 70s have been successfully treated, though younger, healthier patients generally tolerate the therapy better. The decision involves weighing the potential benefits against the very real risks, a calculation that looks different for a 25-year-old with decades of life ahead versus a 75-year-old with multiple comorbidities.

The most feared complication of CAR-T therapy is cytokine release syndrome, or CRS. When millions of engineered T cells simultaneously attack cancer throughout the body, they release massive quantities of signaling molecules called cytokines. About 30-60% of patients experience some degree of CRS, ranging from mild fever to life-threatening illness requiring intensive care.

In its mildest form, CRS causes flu-like symptoms: fever, fatigue, headache, and muscle aches that resolve in a day or two. At the severe end, patients develop dangerously high fevers, plummeting blood pressure, difficulty breathing, and organ dysfunction. These patients often require ICU admission, supplemental oxygen, and medications to support blood pressure.

Cytokine release syndrome affects 30-60% of CAR-T patients, but improved management protocols using drugs like tocilizumab have made even severe cases much more survivable than in early trials.

The good news is that doctors have gotten much better at managing CRS. They now use grading systems to assess severity and employ targeted treatments like tocilizumab, a drug that blocks interleukin-6, one of the key cytokines driving the syndrome. Tocilizumab can dramatically improve symptoms within hours, though it must be used carefully to avoid suppressing the anti-cancer response.

The second major concern is neurotoxicity, technically called immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome or ICANS. This can cause confusion, difficulty speaking, tremors, seizures, or even loss of consciousness. ICANS typically appears a few days to a week after CAR-T infusion, often after CRS has begun to resolve. Most cases are reversible with supportive care and medications, but monitoring is critical.

Recent research has identified ways to reduce these risks. Scientists at Memorial Sloan Kettering developed a compound that can temporarily suppress CAR-T cell activity, essentially hitting a snooze button if the immune response becomes too intense. Patients receive the drug during the high-risk period for CRS, and it wears off naturally, allowing the CAR-T cells to resume their cancer-fighting mission.

Let's address the elephant in the treatment room: CAR-T therapy costs between $373,000 and $475,000 per treatment for the cellular product alone. Add in the required hospitalization, monitoring, supportive care, and management of complications, and total costs can exceed $1 million.

Why so expensive? The manufacturing process is extraordinarily complex. Each treatment is custom-made for a single patient, requiring specialized facilities, highly trained personnel, and stringent quality control. Companies must maintain that infrastructure even when production lines sit idle. The individualized nature means they can't achieve the economies of scale that make most drugs affordable.

Insurance coverage exists but varies. Medicare covers approved CAR-T therapies, as do most private insurers. However, the reimbursement models are still evolving. Some hospitals and manufacturers have negotiated outcome-based agreements where payment depends on whether the treatment works, though these remain relatively rare.

The broader concern is access. Not all hospitals can administer CAR-T therapy. It requires specialized facilities capable of managing severe complications, 24/7 access to ICU beds, pharmacy services familiar with supportive medications, and multidisciplinary teams trained in cellular therapy. This concentrates treatment at major academic medical centers, meaning patients often must travel long distances and stay near the hospital for weeks of monitoring.

The cost-effectiveness debate continues. Proponents argue that a single $500,000 treatment that cures a cancer patient represents better value than years of chemotherapy, supportive care, and hospitalizations that might cost $300,000 annually without producing a cure. Critics counter that the upfront costs strain hospital budgets and insurance systems, potentially limiting access.

Researchers aren't satisfied with 50% remission rates. They're developing next-generation CAR-T cells designed to overcome current limitations, and some of these innovations are already in clinical trials.

Dual-targeting CARs attack two proteins simultaneously, preventing cancer cells from escaping by losing a single marker. One trial is testing CAR-T cells that target both CD19 and CD22, aiming to push lymphoma remission rates from 50% to 70-80%. The logic is sound: cancer cells that drop CD19 to evade detection still express CD22, and vice versa. Targeting both eliminates that escape route.

"The question is, if we do that, can we take that 50% remission rate in lymphoma and bring that up to 70% or 80% by adding in a second target?"

- CAR-T Researcher, University of Colorado

Allogeneic or "off-the-shelf" CAR-T cells could solve the manufacturing bottleneck. Instead of using each patient's own T cells, scientists are engineering universal donor cells that can work in any recipient without causing graft-versus-host disease. These products could be manufactured in large batches, stored frozen, and deployed immediately when a patient needs treatment. No three-week wait, no risk of manufacturing failure, and potentially much lower costs.

Armored CAR-T cells carry extra genetic modifications to help them survive in the hostile tumor microenvironment. Some produce their own immune-stimulating cytokines. Others express proteins that block suppressive signals from cancer cells. These enhancements aim to make CAR-T cells more persistent and effective, particularly in solid tumors where the cellular neighborhood actively sabotages immune responses.

The solid tumor challenge remains formidable. Blood cancers circulate freely, making them accessible to CAR-T cells traveling through the bloodstream. Solid tumors are fortresses, surrounded by physical barriers and immunosuppressive cells that block T cell infiltration. They also lack universal surface proteins like CD19, forcing researchers to identify tumor-specific targets that won't cause harm when attacked in healthy tissues.

Still, progress is happening. Early trials are testing CAR-T cells against mesothelin in mesothelioma, GD2 in neuroblastoma, and HER2 in certain solid tumors. The results so far are modest compared to blood cancer outcomes, but researchers are learning how to combine CAR-T with other treatments to break down tumor defenses.

The clinical trial data tells one story. Patient experiences tell another, equally important one. Emily Whitehead became the first pediatric patient to receive CAR-T therapy in 2012, at age six, when she was dying from acute lymphoblastic leukemia that had resisted every other treatment. She's now a healthy teenager, cancer-free for over a decade, living proof of the therapy's potential.

Not every story ends that way. Some patients don't respond. Some achieve remission only to relapse months or years later. Some experience severe complications that, while survivable, leave them weakened. The therapy demands a lot from patients and families: weeks away from home, frightening side effects, uncertainty about outcomes, and the emotional toll of pinning hopes on a last-chance treatment.

Real-world evidence studies tracking patients outside clinical trials show results consistent with the controlled trial data, suggesting the therapy's benefits translate to everyday practice. Patients report improvements not just in survival but in quality of life, particularly when compared to the continuous chemotherapy they would otherwise require.

The patient journey typically involves several weeks of preparation, the treatment itself, two to four weeks of hospitalization and close monitoring, then months of follow-up as the CAR-T cells establish themselves and the immune system recovers. Many patients describe the first few days after infusion as the hardest, with high fevers, confusion, and physical exhaustion. But for those who respond, the cancer burden drops rapidly, often visible in blood tests within weeks.

We're still in the early chapters of the CAR-T story. The first FDA approval came in 2017, less than a decade ago. What's accomplished so far represents the Model T phase of a technology that will inevitably become more sophisticated, more accessible, and more broadly applicable.

Several trends seem likely to shape the next decade. Manufacturing costs should decline as companies refine processes and potentially move toward allogeneic products. Success rates should improve as researchers identify better targets, optimize CAR designs, and learn to manage side effects more effectively. The treatment should move earlier in the disease course, potentially preventing relapses rather than just treating them.

The next decade will likely see CAR-T therapy move from a last-resort treatment to an earlier intervention, with off-the-shelf versions dramatically reducing costs and wait times.

The solid tumor challenge will likely require combinations: CAR-T cells plus checkpoint inhibitors to unleash natural immunity, or CAR-T plus oncolytic viruses to break down tumor barriers. Success may come in specific tumor types before broadly applicable approaches emerge. Researchers are also exploring CAR-T therapy for autoimmune diseases, using the same technology to eliminate the immune cells causing conditions like lupus or multiple sclerosis.

Regulatory frameworks are adapting too. The FDA has established expedited pathways for cellular therapies, recognizing both their promise and the urgent needs of patients with few options. International collaboration is increasing, with trials running simultaneously across continents and data sharing accelerating discovery.

CAR-T therapy represents more than just another cancer treatment. It's proof that we can fundamentally reprogram human biology, that personalized medicine can work at scale, and that some cancers once considered death sentences might actually be curable.

The challenges are real: daunting costs, access limitations, side effect risks, and the reality that it doesn't work for everyone. But for patients running out of options, CAR-T therapy offers something precious, a genuine shot at long-term survival that didn't exist before.

As manufacturing improves and researchers crack the code on solid tumors, CAR-T should transition from last resort to earlier intervention. The patients who volunteered for early trials and the researchers who persisted through failures built the foundation. Now the question is how fast we move from "this works in some blood cancers" to "this works reliably across cancer types," from limited academic centers to broad accessibility, from prohibitively expensive to cost-effective.

Your immune system evolved over millions of years to protect you. CAR-T therapy teaches it one new trick, but it's a trick that might matter more than all the others combined: the ability to recognize cancer, attack it relentlessly, and remember it so it can't return. That's not just a treatment. That's the beginning of a cure.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

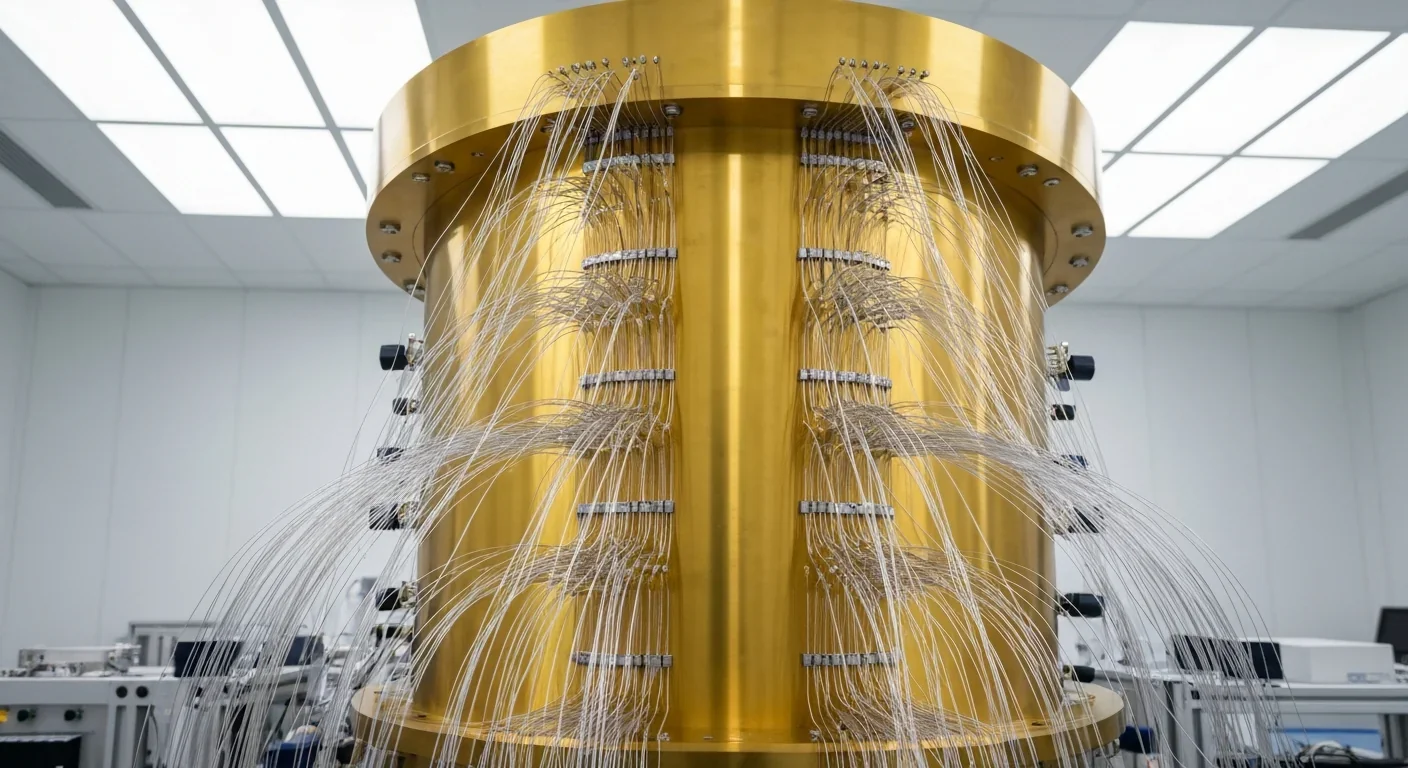

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.